Members of Madron FC in 2010

In 2011 I flew to London and traveled to Cornwall, on what writer Geoff Dyer described to me as “the longest train ride of your life,” and he wasn’t wrong. I wanted to meet the country’s worst soccer team, and understand that mindset. Turns out they have a pretty good sense of humor about it. This story was originally part of my Jock Itch book project (previous installments here and here). I’m sharing it here because, why not? A shorter version was performed at Vesuvio Café in San Francisco.

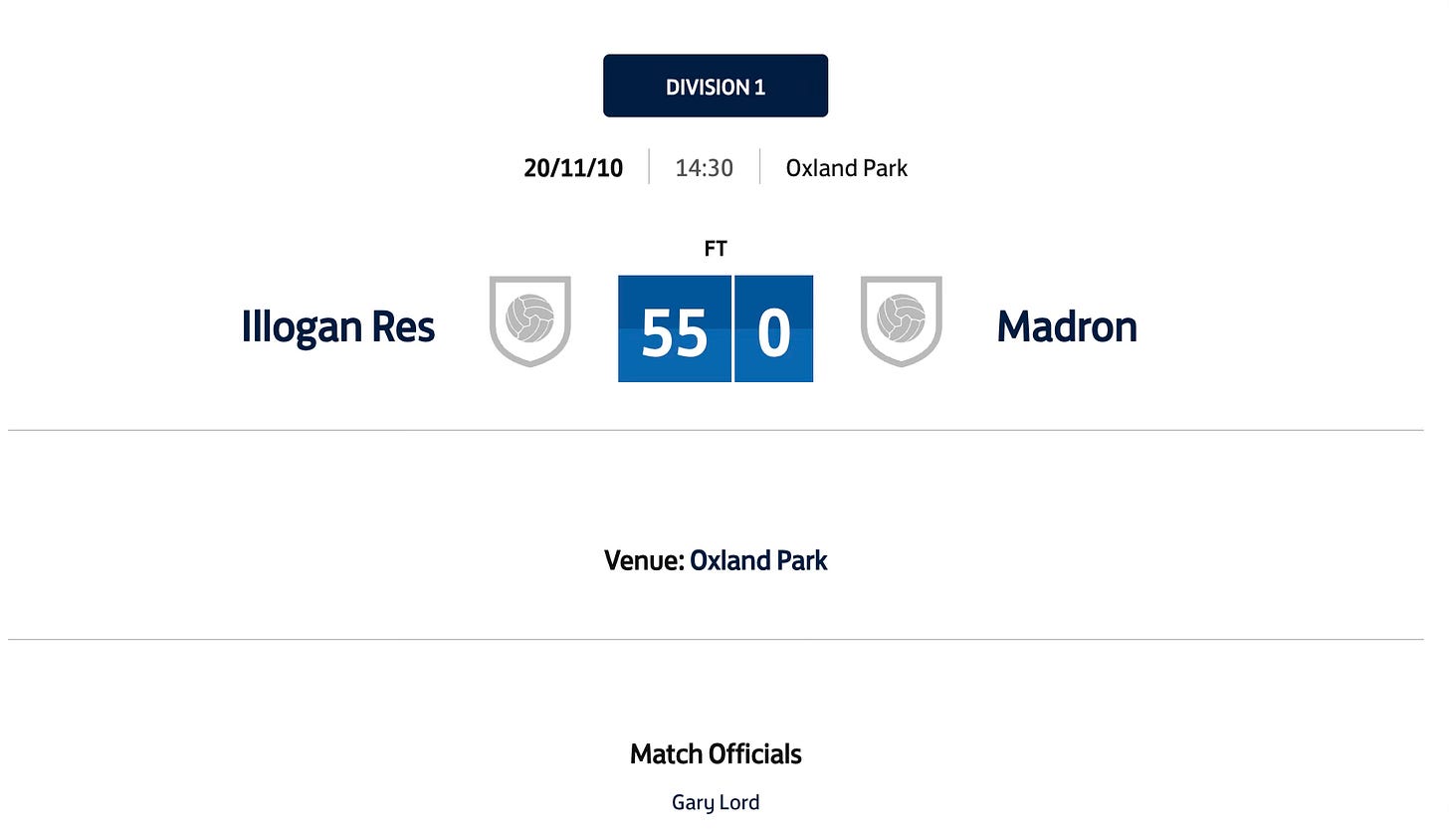

I spot purely by accident a news story about a soccer team in Cornwall, England. They were not doing well in the 2010-2011 season. In fact, they made international headlines: “Manager Admits Football Team is ‘Probably Worst in Britain.’” Apparently a team from Madron, a Cornish village of 1,400 people, had lost a match 55-0. Most soccer matches are decided by one or two goals. This was beyond anyone’s comprehension. A humiliating slaughter. One journalist calculated that on average, opposing team Illogan Reserves scored a goal every two minutes of the game.

Many team members quit. Some were so embarrassed they skipped the squad’s official photo shoot. Manager Allen Davenport was forced to hunt for replacement players atop barstools of local pubs. He admitted to reporters, “I know everybody is probably laughing at us but we will battle on…we have no plans to stop.” Madron (pronounced MA-drun) finished dead last in their division, giving up an astounding 407 goals without scoring a single point themselves.

And yet, there was something intriguing about this legion of losers. They never forfeited a match. They never gave up. At the end of the season, a newspaper reported that Davenport gave every remaining player a trophy. Just for hanging in there. Despite being the laughing-stock of England, the team still forged on.

I don’t know a thing about soccer, but I I keep thinking about this story, and how it epitomizes the concept of losing, how bizarre this must be to bottom out on such a magnificent and humiliating scale, and I’m thinking about it over and over, and finally I can’t take it anymore, and cash in some miles, and book a trip to Cornwall.

As soon as I check into my hotel in Penzance, a town of about 20,000 situated at England’s southwest tip, there is a message waiting for me from Allen Davenport. I’ve timed my visit to coincide with Madron’s regular Saturday match, which was listed on the FA Division 2 website. I return his call. “It’s been cancelled,” he says, breezily. “Not enough players showed.” I have just traveled 5,603 miles, and there is no game.

There is another one next Monday, of the Madron reserve squad, which plays in Division 4. Which is perfectly fine. To watch the second-tier team of England’s worst, in a lower division, that’s even better. I will now be seeing the worst of the worst, the players who weren’t good enough to make it to the worst team in England. And in a sick way, that makes me happy.

I tell Davenport I’d like to check out the village of Madron, which is two miles up the road, and he tells me don’t bother. There’s nothing there. But he will show me the field. King George V Playing Field, the home pitch of the Madron FC. I’ve looked it up on Google satellite maps. From above, you can see that the field is actually crooked.

Davenport pulls up to my hotel in a Citroën van, and we zoom over to Madron, which is essentially two pubs and a cluster of drab grey buildings. We pull down a dirt road and park, and here it is. The first soccer field I’ve ever seen in my life.

Growing up in Montana, there was no soccer at all. My first experience was in San Francisco, walking past a British pub at 9 am, when European matches are played, and the ex-pats spill out onto the sidewalk in a drunken rush of adrenalin musk, chatting and smoking. The concept is easy enough to grasp—kick the ball into the net. But because that so rarely happens, a match seems to be 90 minutes of 22 people running back and forth across a field, kicking at each other.

The soccer magazine I bought at Heathrow explains little to the newbie. It’s a very specific world, a byzantine global cabal in which players are photographed in three poses: 1) heroically hoisting a fist or championship cup; 2) heroically leaping in mid-air to kick a ball; and 3) an open-mouthed animalistic growl, as though one were just impaled by a spear. I do note that in soccer, a coach or manager is never fired, or laid off, or let go. He is always “sacked,” which implies a more unceremonious action, like a body bag heaved off a truck into a ditch.

Davenport is from Manchester originally, and has played football most of his life. In his youth, he saw all the concerts—Beatles, Stones, Gerry & the Pacemakers, Tom Jones. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, but he does have six ex-wives, and has had both knees replaced. He has lived in Penzance for 30 years, most of that time with Madron FC. He’s now 71, with the energy of a 25-year-old, and wears denim shorts no matter the weather. And he is hilarious. But he doesn’t want to talk much about his own career. “It’s not about me.”

Madron was not always a crap team, he explains. At the end of the 2009-2010 season, they were ranked #1 in Division 2 of the Mining League, winning 26 of 28 matches. As is the rule in British football, they were doing so well they got bumped up a division for the following year. But three days before the season started, Davenport tells me, the manager left and took most of the players with him. So not only did Madron begin the year in a new and larger division, there were only seven players left, to play against 11-man squads. The oldest was age 17.

First match of the season was August 28, 2010 against Illogan Reserves, and Madron got basted, 0-11. They continued losing in spectacular fashion (0-27 against Trevenson United, for instance), until a rematch with Illogan on November 20 racked up the 55-0 loss. Eleven Illogan players scored goals, one of them finding the net ten times. After the story hit the London press, Davenport’s phone rang with reporters from Japan, New Zealand, and throughout Europe and South America.

He refers to that match as “getting leathered.” He says he asked the team beforehand if they still wanted to do it. All of them said yes.

“How can you knock ‘em?” he exclaims. “You’re turning up every week to play, knowing that last week you got beat 55-naught. And you’re gonna play another good team this week. You can’t knock ‘em. All I say is, ‘Look, enjoy it. Enjoy your football. Come off, have a laugh.’ You go in, you have your food with the lads, and the other team come with us. They get food, we get food, and you have a good laugh together.”

Last year Madron slid to the bottom of Division 1. And yet, astonishingly, because of that horrific loss and season, it has become more popular to go out for the Madron team. This year they have 65 players between the two squads.

To finance the team, Davenport has instituted a £2 charge for training, which happens each Wednesday at an outdoor field hockey pitch. But he can afford to pay the players only £6 a game (about $10 US), which is the bane of any manager’s existence. Many players simply switch teams during the week, because they can make £10 or £20 a game in another town. Someone could quit Madron FC on a Wednesday, and then be playing against them that Saturday.

“There’s too many teams!” exclaims Davenport. “There must be 50 teams down here.” Every single village in Cornwall has at least one team, maybe two or three. To his mind, there’s no opportunity for any one team to get really good.

(For some perspective, England currently boasts about 7,000 football squads, over 140 leagues and nearly 500 divisions within those leagues. And these are just the teams that pay players. The amateur numbers are limitless. All you need is a ball.)

Davenport unlocks a gate and we walk out onto the pitch. A beautiful field of green grass. Nobody helps him with maintaining the field. Is he okay with doing all this work himself? “The tractor belongs to me,” he shrugs.

He shows me inside the pavilion, which is really more of a well-built wooden shed. There are showers and dressing rooms, one wall is covered with awards, from the days when Madron once fielded really good teams. A framed shot of young kids in Kenya, posing for their team photo, wearing shirts and shoes. The Madron team donates uniforms and shoes to them each year. “But no socks,” he says. “They say it’s too hot.”

We stand in the kitchen, he shows me a stove and opens a little fridge—suddenly WHACK! The window is covered in yellow goop.

“Dammit!” Davenport mutters, and he’s out the door like a flash, running on two artificial knees. I follow him around the building and we observe the unmistakable residue, sliding down the glass. Somebody has egged the Madron FC pavilion. Allen looks around a nearby vale of trees, but the culprit has already vanished. “I think I know who it was,” he scowls. “It might be one of my footballers. He lives around here. I’ll get on him next Monday.”

I ask him, why would one of Madron’s own players throw an egg at the pavilion of his own team? While his team president was inside? He just shakes his head.

Not only is Davenport team president, he hires managers for both the first and second team. He built the pavilion. He runs all the club finances, scouts for new players, drives players to all the matches for the season, he pays the referees and coaches, he pays each player, he pays for all the jerseys, balls and equipment. If there’s not enough players, he’ll join the game. After each match he takes the players out for beers and sausages. He estimates he’s spent close to £15,000 on the Madron club. It’s extraordinary.

Davenport drops me off in Penzance, and after a stop at a pub where a guitarist named Jonathan English does a superb note-for-note version of Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” I head back to my hotel, a bit baffled. I have three days to kill before I can witness Madron FC in action. The anticipation is odd. I’m hoping that they can still lose. I mean, that’s why I’m here. It’s the reverse version of getting excited about a sporting match.

There’s something about traveling to England specifically for soccer. This is the Motherland for America’s football and baseball (directly lifted, respectively, from British soccer and rugby, and the children’s game of rounders). People have been kicking balls in the UK since at least the 9th century, when medieval football was played between mobs of neighboring villages, often around the time of the harvest. Participants kicked and dragged an animal bladder through the streets, occasionally punting it into the balcony of the opponent’s church. This was centuries before jousting.

Even Cornwall had its own offshoot, Cornish hurling, played with a silver ball, which villagers would throw and kick through streets and fields, on an informal pitch that might extend for 20 square miles. As with medieval football, there were no referees or rules of any kind. People frequently switched sides during the game. Old people were trampled. All you needed was a ball and two groups of competing hamlets. And everybody got drunk afterwards.

The concept of play, without any motive except enjoyment, has history in every continent, but we must thank the Brits for formalizing these games, writing up rulebooks, and then foisting the new sports onto their colonies. Modern English football rules date to 1863, and emerged initially from public, or college prep schools, as an activity for upper-class students. When rugby and football parted ways, rugby continued as a sport for the educated, and football gained traction in the lower classes. America soon adopted rugby in its colleges, tweaked the game into a separate offshoot they called “football,” and developed a new set of intercollegiate rules, including something called a “forward pass.”

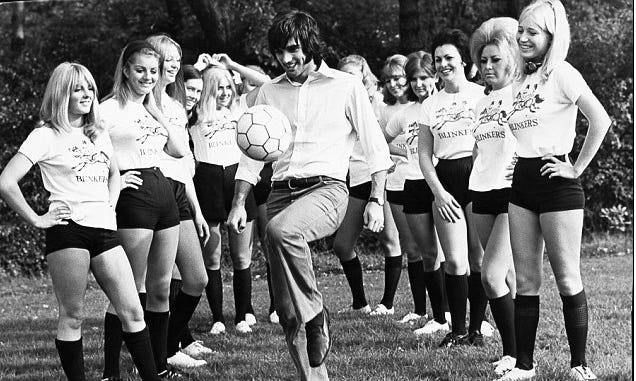

Before I descend into a Wikipedia black hole, I pull back and search YouTube for videos of the only two British athletes I really know anything about, football legend George Best, and darts champion Jocky Wilson. Because my friend Alan Black has told me about them.

A 1981 clip of George Best playing with the San Jose Earthquakes is titled “George Best…best goal ever.” I don’t know shit about soccer but it’s obvious he was an incredible talent. Best receives a pass from a teammate, in the middle of the field, and battles his way through six defenders, flicking the ball between their legs, kicking, nudging, sneaking and faking shots with both feet, and suddenly fires the ball off his left foot into the right corner of the net. The stadium explodes. I recheck the timing, the entire moment takes eight seconds. It’s herculean. At 35 years old, he was still a freak of nature.

Documentaries detail how Best was once the greatest in the game, the sport’s first rock star, all 1960s flash and smiles, arguably as popular as the Beatles. He owned a clothing boutique. He was photographed with beautiful women. He was cheeky to the press. He moved around the world, playing with an astonishing 17 different teams before retiring in 1983. He battled alcoholism and bankruptcy, lost his license for drunk driving, sold off his awards, even recorded a song for a fitness album. He received a liver transplant and immediately celebrated the procedure by heading down to the pub. He made it only to 59 before dropping dead from “multiple organ failure.” A spectacular flame-out. His most famous quote sums it up: “I spent a lot of money on booze, birds and fast cars. The rest I just squandered.”

Jocky Wilson was a different kind of sports star. To American eyes, English dart videos are just bizarre—a large room filled with people smoking and drinking, staring intently at two guys flicking little darts at a target. You initial impression is, “This is a sport?” It’s like watching people shoot pool. You can’t really call them athletes. Especially Jocky Wilson, a corpulent little Scottish man with no teeth, who competed in tournaments accompanied by a cocktail and a lit cigarette, looking like he just woke up on the sofa. There is a long YouTube video of Jocky winning the 1982 Embassy World Darts Final, that somebody has posted in 17 segments. You could devote your whole day to watching Jocky Wilson play darts.

Like Best, Jocky loved his drink. And also died from it, as it turned out, just three weeks prior to my visit. He appealed to the everyman, in part because he looked like most people in the pub—pasty, jowly, wearing a sloppy shirt, pausing to light another gasper and gulp from a glass. But there is definite drama in watching a portly alcoholic step up to the line, and with some form of unorthodox janky style, shove the darts at the board with his beefy arms, and slay opponents one by one, with the announcer crying, “Jocky Wilson! Champion of the world!” Like Best, his post-retirement years were spent in bankruptcy, fighting diabetes and alcoholism, living on disability, until his heart gave out at 62.

I close the laptop, I can’t watch any more. I’m not sure what to make of these two guys. They were brilliant at what they did. Two broken men who happened to emerge in the era of television, when their achievements were beamed out to every pub and housing project from Port of Ness to the English Channel. In some ways, fame killed them. Humble beginnings in post-war Ireland and Scotland do not prepare a person for sudden wealth and endless rounds of drinks and fans yelling your name on the street. Both of their deaths were splashed all over the UK media. Best’s hometown of Belfast, Ireland named the airport after him. Wilson’s funeral in Fife, Scotland was jammed with over 400 mourners. What’s the lyric from the Motörhead song? “But that's the way I like it, baby / I don't want to live forever.”

-----------------------------------------------

After Margaret Thatcher shut down the nation’s mines and broke the unions, I am told, Cornish towns rebooted themselves as tourist destinations. Fortunately Cornwall is a pleasant place to visit, the weather is nicer than other parts of England. The buildings are not covered in soot. Fresh air, local seafood, and the pasties are everywhere. Originally a self-contained sandwich invented for Cornish miners to eat with grubby fingers, the pasty is ubiquitous throughout England, but in Cornwall, the regional pride is audible. They invented it. People swear by their favorite chain shops. Men, women, and children all start their day munching on pasties.

The Penzance newspapers host endless discussion about a proposed “pasty tax.” England already taxes food sales if the food is hot, or “above ambient temperature.” Pasties have traditionally been grandfathered in, sans tax. But Britain needs the money. Should the pasty be now taxed? What constitutes “ambient” temperature? What if you bought a pasty that had been taken out of the oven for a bit, and was allowed to cool to a temperature cooler than “ambient”? Should the government stick a thermometer inside every pasty before purchase? The debate rages on for days.

Here is something the guidebooks don’t tell you—a fresh pasty is scalding fucking hot. The first bite will sear the flesh of your mouth and you’ll scream like a baby on an airplane. After some trial and error, I find that it’s best to break the thing in half, and wave both ends about in the cool grey British air until it’s edible. But they are quite good.

Cornish history is one of resilience. The local museum is filled with paintings of glum women staring into the distance, children intensely concentrating on menial tasks, and scenes of men laboriously hauling fish from the ocean. But what has disappeared is the Cornish language. As with the Welsh dialect, it effectively disappeared in the 1700s, after England “absorbed” both regions. Nobody really speaks it anymore. Some local books are written in Cornish, but it’s impossible to read if you’ve never heard it spoken aloud.

Penzance is immediately associated with the musical “Pirates of Penzance,” but Gilbert and Sullivan deliberately set their story in Penzance because there wasn’t any history of pirates here. (Although other accounts do mention Turkish pirates inhabiting the shores in medieval times. Whatever, it doesn’t matter now.) Penzance has a recognizable showbiz connection, and they play it up. Signs around town advertise pirate names and pirate imagery. The rugby team is named the Cornish Pirates. On my train ride from London, the car is filled with a group of loud teenage girls dressed as buccaneers, wearing striped tights and corsets and brandishing plastic swords. Hey, you push whatever you have.

Since I’m here for soccer, I drop by the Longboat Pub, across the street from the train station, where the flat-screens are beaming Liverpool against Iverton in the Premiere League semi-finals. It’s England’s top tier of soccer, and Wembley Stadium is completely sold out. This will be the first British football match I’ve ever watched. The bar is packed for the 12:45 kickoff, and almost every person is wearing Liverpool red, from a baby, to some senior citizens, even a large hairy dog wears a red vest.

This experience of watching sports is ritualistic and intense, very different from the States. In soccer, the clock never stops. There are minimal commercial breaks. Aside from an occasional muttered epithet, a grumble of advice, or a hand wiping the face in frustration, it’s a completely silent experience. It’s far, far too nuanced to not pay complete attention. Iverton scores first, and then Liverpool scores twice, coming from behind and winning with a head shot backwards into the net, by a player with a pony tail who did it perfectly.

Later I learn just how maddening the Premiere League can be to follow. It’s actually called the Barclay’s Premiere League, after the bank that sponsors it. The top teams are always the same—Manchester United, Manchester City, Chelsea, Tottingham, and Arsenal. Half of the teams are owned by gazillionaire foreigners, from Egypt, Russia, Abu Dhabi, India, Malaysia, America, and elsewhere. A startling number of players are not British. Unlike sports in the US, the team jerseys are enthusiastically splattered with names of sponsors (Emirates! Samsung!). Some years back, the Football League (from which the Premiere League evolved) was even named the Coca-Cola Football League. It appears that long ago England threw up its hands and said, “What the hell, we need money—everything’s for sale.”

People suggest that I take in a rugby match while I’m here, and so the next afternoon I drop by the local field, where the Cornish Pirates are hosting the visiting Bedford Blues. I stand at the fence near the grandstands, and realize that everyone in this group appears to be wearing blue clothing. I’m wearing blue clothing. Seems kind of coincidental. And only then does it dawn on me that I’m in the middle of the Bedford supporters section. There’s not many, only 15 or 20 made the seven-hour drive.

I’m kind of excited to watch rugby. This is the sport most closely thought of as the origin of American football. The players are big brutes, legs like tree trunks, tight jerseys that make them look like superheroes. No pads or helmets, although a few guys wear a shower cap-style headgear. But the game is perplexing. Soccer at least is dumbed down enough for idiots like me to understand. One kick into the net equals one goal. Rugby seems mired in a surplus of rules which make no sense.

There’s a moving amorphous huddle, or scrum, that grunts and heaves, and eventually squirts out the ball in an overly deliberate maneuver. Penzance scores first, in front of us, and there’s some kind of kick, which hits the goalpost. Mysterious numbers of points start rolling up on a scoreboard. What’s going on? Bedford kicks high up in the air, there’s a pile-up of men grunting and then we’re back to running and tackling, people passing the ball down a line as if following a script. Whenever the ball goes out of bounds, and is tossed back in, both teams hoist up players on shoulders to fight over it, like children playing Marco Polo in a swimming pool.

The game seems very anachronistic in a way that soccer is not. And all this time, the Bedford supporters around me erupt in song, chanting, “Bed-fuhd! Bed-fuhd!” One will start, and the others pick it up, like a pet shop filled with birds.

A Bedford man stops chirping and asks a woman, “Who’s the referee?”

“Pierce,” she answers.

“He like penalties?” he asks.

She scowls. “He’s young.”

Ouch. I wouldn’t want to be Pierce. I leave at halftime. I’m not really feeling the rugby. I hook up with some musicians and we walk around Penzance, as they show me things about their town.

Liam Jordan is 22, he grew up here in Penzance, moved to Brighton for a bit, studied music and guitar, then moved back to live with his mom. His favorite football team is Arsenal, and he’s not afraid to sing 10cc’s song “I’m Not in Love,” in a pub. Here’s the oldest continuous movie theater in England, he points. I mention that lots of people go out in shorts and flip flops, even when it’s 40 degrees. He chuckles: “Most people here are eccentric.”

Liam adds that people are suspicious of outsiders, especially Londoners, who come here on holiday, find out they like the area, and buy second homes that sit vacant, jacking up real estate prices for the locals. A common complaint around the world. Rich people and their second homes.

Everyone in Cornwall is familiar with America. Or at least our music, movies, and television. Several people wear American fashion such as the Hollister, California T-shirts. One kid proudly wears a hoodie with the slogan “Montana University,” which is pretty hilarious. I’m from Montana. There is no Montana University.

But most locals have never been to America, and seem to have never met an American. One woman tells me, “You don’t sound like an American,” which I hope to be a compliment. Another woman launches into a long confessional gush about her love of Janet Jackson and Sex and the City. Some people simply refuse to talk to me whatsoever, and one drunken man with a weird Liam Gallagher glazed-eye thing immediately hates me, and seems to be waiting for the appropriate moment to punch me in the face.

Liam and Jonathan take me to The Farmer’s Arms, a fantastic musicians’ pub and hangout owned by two guys named Nigel and Taf. Live music most nights, an open mike every Sunday, acoustic instruments hanging from the wall if you’re up for it. A poster behind the bar advertises the band Alabama 3, most famous for performing the theme song to The Sopranos.

Jonathan introduces me to a group of his friends and then says, “Tell them why you’re here.” I explain my visit is because of the Madron team, and everybody has a hearty laugh. They all remember the news story. Everyone’s first reaction is that it’s hilarious to lose 55-0. And then on second thought, it’s kind of sad. And thirdly, it shows determination to keep on going. Jonathan explains it succinctly: “England loves its losers.”

At the bar I talk to Rik, a huge fan and player of cricket. He arrives every day around 1 pm, and settles into an afternoon of vodka and cokes. He has an artificial leg, but it didn’t stop him from playing cricket for 30 years. He started playing in the military, it was a logical way to use the precision training and discipline. He says it’s the most British of all the sports. He doesn’t follow football, because it’s everywhere. Overexposed. It doesn’t take anything to be a fan. Open the paper, here’s the stats, here’s the gear you can buy, here’s the games, here’s the players out on the town in the photos. All the work is done for you. It’s for idiots. He shakes his head.

----------------------------------------------------

Allen Davenport picks me up on game day, and we stop at the practice facility to gather up a few other players. They pile into the van (“No, the American sits up front”) and one husky guy takes his seat, lifts his leg and squeezes out a nasty bubbling fart. “Ooh, that’s gonna be a wet one,” he announces, to much groaning and nose-wrinkling from his mates. Sport really does transcend all cultures.

We drive about a mile to Madron, and empty into the pavilion, which is bustling with activity, both teams tromping in and out, people setting up the snacks and bevvies. I watch the goalie, the same ruddy-faced guy with gastrointestinal issues, take a final drag from a cigarette and trot out onto the field.

Allen tells me the team they’re playing tonight, St. Buryan Inn, are supposed to be the second team, but he recognizes some faces from their first team. They’ve stacked the deck. Allen says it’s because they don’t want to be seen as losing to Madron.

I notice there is no place to sit and watch. There are no bleachers, terraces, or chairs. There is nothing. Exactly 27 people stand on the sidelines. This includes other players, the coaches, a few children laughing and tackling each other, and myself. If this attendance sounds pathetic, keep in mind that there are two more divisions below this one.

Action commences with the players running back and forth across the field, kicking and yelling. Unlike a quiet soccer television broadcast, it’s continual noise, a cacophony of swearing and shouting of directions and “Peter—watch the middle!” orders by the Madron coaches. The St. Buryan coach doesn’t really say anything, he just smiles and claps once in awhile. His team is larger and faster. He knows he’s going to win. At one point Madron moves the ball downfield, to the surprise of everyone, but then they promptly lose the ball out of bounds. Madron team manager Steve Palmer mutters, “A goal would have been nice.”

There is no scoreboard of any kind. The referee checks his watch for the time. If you lose count of the goals, just ask somebody next to you. Whenever the ball sails over a fence or into a hedge, everything stops and one of the players trots off to retrieve it. The ball even bounces into my chest once, and I toss it back with a proper combination of insouciance and steely athletic grit.

When play first began, Madron’s players encouraged each other with things like “Alright boys, keep it going!” “Cam on, lads!” “Cam on, Madron!” As the match deteriorates, the language devolves into endless variations of “Ah, for FOOK sake!”

The match grinds on and on, punctuated by the kicking and scratching of frustrated men, as the Madron team slowly tanks another one. This is like the behavior of some kind of cult. Watching men in shorts chase a ball in a field that appears to be abandoned, as if one of us popped the lock on the gate and we have to quickly finish before someone discovers we’re here, doing this in a freezing cold evening, with the wind blowing off the Atlantic so hard you can actually hear it, veers quite close to insanity.

When two Madron players get injured, they exit the field limping badly. There is no medic, no trainer. They just hobble off, dripping blood, done for the day. Most of the audience, what there was of it, has already left for the pavilion, where there is at least a break from the wind.

The frustration, the bitter cold, this continual repetition of failure, to me, is a message from above. If I were on the Madron team, I would just quit. I would walk away from it and find something else to do. The negatives far outweigh the positives. How can a person not take this personally? It’s impossible. I did not grow up with a love of football. But watching these guys out on the field, some as young as 16, some in their 40s or 50s, playing despite the score or the context, it’s kind of admirable. It’s like listening to not-very-good musicians play, or watching not-very-good theater. There isn’t supposed to be much of an audience. It’s more about, and for, the people playing.

A whistle blows and the carnage finally ends, if carnage can end in wind-swept silence. The final score is only 5-nil, which everyone is really happy about because the last time they played St. Buryan it was 23-nil. “We are getting better,” the snack seller tells me brightly.

-------------------------------------------------------

After the match, Madron’s players meet at a sports facility called the Hockey Club, where there is beer and pool tables, and video screens play football highlights of much better teams. Allen Davenport moves from table to table with an enormous platter of sausages and French fries, feeding his charges by the fistful. If you’re only getting £6 per game, it’s nice to have some perks. Nobody is very wealthy in this part of England. Most of the players work as carpenters or electricians, one empties dustbins for a living, and others are still in school.

One Madron player, a 38-year-old from Dublin named Fran, has lived in Cornwall for six years. Last year he was playing and managing a team at Ludgvan, another small village just down the road, but Cornwall is tiny, and everyone is on Facebook. He vividly remembers the 55-0 slaughter.

“Oh, I laughed my socks off,” he says. “Yeah, of course. Because it’s just ridiculous. It is. You look at it and you think, ‘Oh my God, no way.’”

Ludgvan’s team trained with the Madron squad together at this facility, and the players all knew each other, he says. “Your instinct first is to have a laugh. And then you think, ‘Hang on, what happened?’ And we found out they had only seven players start the game. Allen played! Under the rules, if one person had walked off that pitch, the game would have been abandoned. They all continued. You gotta give them a lot of credit for it.”

Madron Reserves manager Steve Palmer joined the team last year after the 55-0 debacle. As we chomp on greasy sausages, he tells me he’s played and managed Cornwall teams that played on farm fields. They would literally have to remove the cow before starting a match. When a team showed up without enough players, the opposing squad would lend them some of their substitutes, just so everyone could get to play.

“I’ve been in a position before, with clubs I’ve been with, playing against teams that were short, or strugglin’. During halftime, I said, ‘Look, you’re gonna learn nothing by putting 20 goals past this team. Sit back, play the ball around, learn from this one, ready for next one.’ Because we learn nothing else. We never laugh at the opposition.”

“Illogan never lent them any players,” he continues. “Their manager was on the sideline, and he said, that if you don’t put the effort in and keep going, you won’t play next week. So he forced them to keep going.”

After the 55-0 “leathering,” The Daily Mail quoted Illogan assistant manager Mark Waters as saying, “Nobody enjoys games like that, we certainly didn’t enjoy it…I have nothing but admiration for the seven Madron players, but it does make a mockery of the league…it was a waste of everybody’s time, including the referee’s, but we had to abide by the rules and play the game.”

Steve sniffs. “Obviously he’s not a very good manager.”

Team captain Jason is 24, he goes by “Ving,” grew up in Madron, and has lived there all his life. Although he was on the Madron squad during the 55-nil game, he didn’t play that day. “But I played in the ones like the 27-nil, the 29-nil. There’s the 26, the 21, there’s been loads of them,” he laughs.

I tell him I can’t imagine what it must feel like to be 20 goals down, in a game.

“It’s very hard to come back from it, obviously,” Ving says. “Within the first three goals, heads do drop. But I dunno, just playin’ football, and bein’ out on a Saturday, rather than going to the pub on a Friday night and being really hung over. You get to turn up and have a laugh with the lads, and go out and play football. I go out for fitness, basically.”

He’s so deeply connected to the Madron town, and the team, I ask him how his friends reacted to the “leathering.”

“They always have a laugh about it,” says Ving. “‘I play for the worst team in England!’ Stuff like that. I laugh along with them. But in my eyes, I can see that we’re getting better. And that’s why it doesn’t faze me at all.”

Finally, I meet John William Cornish, a smallish 17-year-old who grew up in Penzance and just started playing adult football this year, after an introduction to Allen Davenport through his grandfather. He had never seen Madron play until joining up, so he missed the infamous previous season, but he says his friends and family supported him joining the Madron squad, despite the reputation. “My mum’s not a big football fan, but I think she likes the fact that I’m getting out and exercising. And not staying in the house with the Xbox, or something.”

I’m not really sure what to make of the cheery Madron team. I had expected a bunch of sad-sack losers, moping and trudging from game to game, ridiculed by the nation, pelted by rotten fruit whenever they stepped outside. But it’s not like that at all. They’re having fun on a Saturday, getting fresh air and playing a game with their friends. There’s just fewer points on the board.

I arrive back at my hotel, still somewhat confused, and discover someone has dropped off an official Madron FC team jacket. On the back it reads the sponsor’s name, “Dan Tellam-Woolf Painting & Decorating Contractor.” I put it on and zip it up, realizing it still smells of sweat, the sad odor of bottom-division football. The jacket of the worst team in the entire sport of soccer. It almost makes me cry. And I tell myself right there, this is the only team logo I’ll ever wear on my back.