Jock Itch #2: The Iron Bowl

Another memoir excerpt about the nastiest rivalry in American sports

I was not learning any cogent insights about why I didn’t care about sports. I’d read a bunch of history books, recounted here in the last segment of this memoir. But I needed to lean in more, to witness something firsthand. Why would anyone willingly dive into such a subject if it wasn’t appealing to them? I don’t have a logical answer. I think that’s how I’m wired. Learn what you loathe, I suppose.

It occurred to me that conflict, competition, and rivalry played prominently in the appeal of sports. People got excited when the stakes were high, when there was some real drama to taste. Unfortunately, I didn’t have much of this in my background. The most contentious topic I can recall is whether disco was good or evil.

Perhaps if I were to witness a true rivalry, all of this would fall into place in my head. Team owners have apparently depended on this emotional manipulation for a very long time. In the 1800s, when team sports first established in the U.S., franchises were already choosing which teams would be their rivals. It was strictly a cash grab. Select an enemy town, spark some hustle in the players, get the fans all worked up, and watch the ticket sales line your pockets.

I somehow stumbled upon the allegedly worst rivalry in American sports—the annual Iron Bowl college football matchup between the University of Alabama and Auburn University. The more I read about it, the more it seemed completely insane. People couldn’t even remember when the game began, either 1892 or 1893. The series was halted in 1907 because of an extended argument over officials, and although only 160 miles apart, the two schools refused to play each other for the next 40 years. After state legislators intervened, the Iron Bowl resumed, and it now generates up to $15 million each year for the state. Hatred sells.

This sounded fantastic. I had to see it for myself. Even though I’d never been to Alabama before, and I would be dropping my Yankee ass into the heart of Dixie, I cashed in some miles and booked a flight to Birmingham.

Scholars have examined the obsession of Deep South football for years. One theory holds that it was a Northern sport originally, and if Southern teams could beat the Northerners at their own game, they would no longer be looked down upon as second-class citizens. The battlefield violence provided a physical and emotional release to counteract the rage of Southern defeat in the Northern war of aggression. The Confederate focus on close-knit family, and a firm belief in Christ Almighty, remain essential ingredients of Southern football. This sounded reasonable enough.

But the Iron Bowl defied such lofty analysis. This wasn’t the Confederacy versus the Union. This was simple hardline South-on-South prejudice: the little redneck hillbilly school (Auburn) versus the over-funded spoiled-rich-kid corporation masquerading as a university (Alabama). Within the state, it was a deadly serious affair between two teams despising each other, and most importantly, enjoying despising each other. Whoever lost would stew in the juice of failure for 364 more days until the following year.

This one game had birthed dozens of books and documentaries, enough T-shirts to clothe the Third World ten times over, and never-ending enmity to keep the citizens of Alabama arguing scores and players and lineups, and even after the last iceberg melts and a massive flood chased the human race into the mountains, they would still be bitching about the lazy officials in the 1986 “Reverse to Victory” upset. Yes, there was an official Iron Bowl song.

Even the two teams’ identities made little sense. Alabama’s Crimson Tide was so named because in 1907, supposedly, when the Iron Bowl was played in a sea of red mud, Alabama held favored Auburn to a tie and a sportswriter coined the phrase “Crimson Tide.” It was not, as some suggested, a reference to menstruation. And yet, Alabama’s slogan is “Roll Tide,” and its mascot is an elephant.

Since at least 1916, Auburn’s battle cry was “War Eagle.” The school even features a raptor center, which raises and trains the eagles to fly around the stadium. But their actual mascot isn’t an eagle, it’s a tiger.

Maybe I was looking at this too logically, but shouldn’t it just be “War Tiger” and “Roll Elephants?”

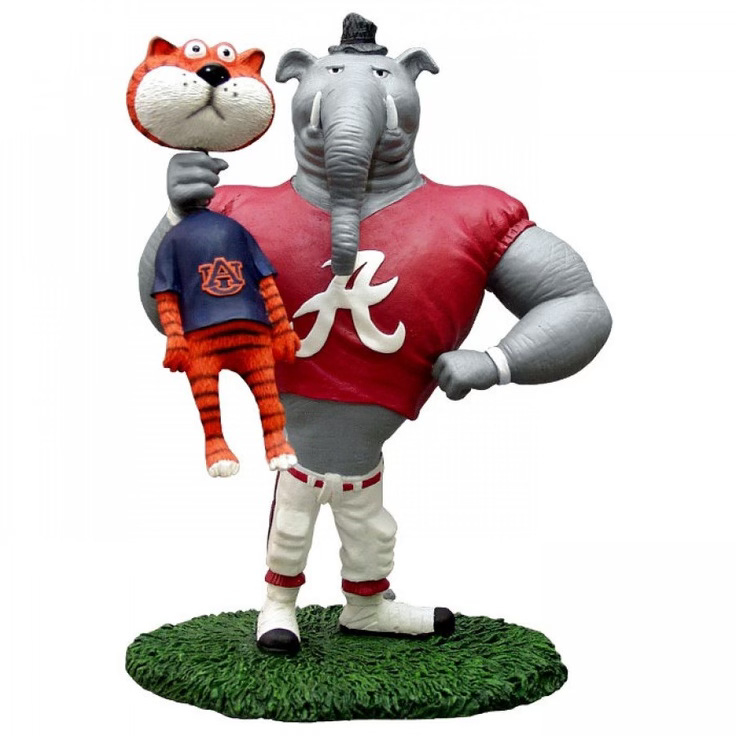

One thing was for certain, the Iron Bowl online universe roiled with animosity. Alabama fans gleefully shared a YouTube video of the Auburn mascot, an eagle trained to fly around the stadium before each kickoff, which got confused in 2011 and smacked into the window of the press box. Auburn fans countered by posting clips of the “Punt ‘Bama Punt” Iron Bowl from 1972, where Auburn blocked two Alabama punts within a few minutes, scoring two touchdowns and winning the game. I discovered all sorts of nasty trinkets for sale, from name-calling swag items, to statues of straight-up team mascot violence: an elephant (Alabama) strangling a tiger (Auburn), by its neck (see above).

Another characteristic I found compelling: both teams were childishly sore losers. Cameras focused on the fans, their tear-stained faces slathered in team colors, hands covering their mouths in silent horror, as if witnessing a mass shooting instead of a pass interception. Thousands and thousands of people gathered in one location, all feeling like life has just ended. I couldn’t wait.

The night before the game, I drove through Tuscaloosa’s U of Alabama campus and, like a sarcastic moth, was drawn to a giant illuminated sign reading “FAITH AND FOOTBALL.” The church was located right on campus, in between classrooms and student housing. This seemed really odd. I’d never seen a chapel so embedded in a university setting before. I pulled over my rental car to take what I thought would be some hilarious ironic photos, which I could later show to people and say, “They hijacked Jesus for football—isn’t this batshit fucking crazy?” A college girl with a backpack walked by and exclaimed in a rich Alabama drawl, “It’s a real nass sign, idn’t it!”

At my hotel’s complimentary “Continental breakfast,” I met two brothers, Steve and Dave, also on their way to the game. Both were Alabama grads. Steve pointed to my blue jacket and said, “Y’all better put on some red.” ‘Bama red. The home team. Auburn’s color is blue. When I asked why, they both shrugged, as in “It’s your funeral.” We chatted a bit longer. My dad was from Texas, so I’m able to temper my Yankee energy if needed. They invited me to their pre-game tailgater, in section C-3 on the Quad. They rented the same space every year.

I found a sweater that had a red stripe, and walked towards the Quad. The blocks around Tuscaloosa’s Bryant-Denny Stadium were growing congested with thousands of ’Bama hats and shirts. The Iron Bowl energy. A sidewalk preacher with a bullhorn ranted about the importance of Jesus Christ. A big red pickup drove up and down University Boulevard, towing a large stuffed tiger with a rope tied around its neck.

Steve and Dave greeted me at C-3. A lot of tailgater scenes can be coarse, even animalistic. These booths were very orderly, laid out in a grid underneath the trees. Proper Southern hospitality, in a way. I was introduced to a few of their friends. One man stood off to the side, eating chili from a styrofoam bowl. “See that guy?” said Steve. “That’s Terry So-and-so. All-star fullback.” I asked if he turned pro. Steve shook his head. Didn’t work out. The man took another plastic spoonful of chili. Waiting to be recognized. I felt sorry for him.

Nearly all of the stadium’s 101,821 seats were filled, and the vibe was chaotic and deafening. Bands played, people screamed, video screens showed highlights of Alabama’s previous championships, giant flags flapped, mascots and cheerleaders jumped about. One could draw a close comparison between this scene and Leni Reifenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will. Especially if one had watched that film on Netflix within the past few days.

This was so not my scene. I sat in my seat, isolated and alone, like a tourist from Latvia, not understanding the language, taking note of the peculiar local customs. People were polite, but very keyed up, glassy-eyed and frenzied with anticipation, ready to launch into a gang fight or a mass suicide. A woman walked past, wearing a button that read, “Go to hell, Auburn.”

The sound system played audio clips of Paul “Bear” Bryant, the revered Alabama coach who died in 1983. His voice intoned stirring motivational quotes, which echoed around the stadium. To be honest, it sounded mostly like an old mumbling Southern alcoholic. Somewhere nearby, in a cemetery shared with generals, I imagined the same voice coming out of a tiny speaker mounted in Bear’s tombstone. If a visitor came close enough, it would trigger a motion sensor, and you’d hear, “Don’t give up at halftime. Concentrate on winning the second half.”

Next up, the opening guitar riff of AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck,” and the Crimson Tide team ran out onto the field, led by Coach Nick Saban. The stadium went Triumph of the Will again. Auburn’s team then entered, greeted by deafening boos.

I later learned that in 2010, as Auburn quarterback Cam Newton took the field in this same stadium, the Steve Miller song “Take the Money and Run” was played, in honor of Newton being investigated for bribery. The sound person was fired.

Alabama huddled for the first play, and screens beamed images of angry-looking elephants staring coldly into the camera, their cheeks smeared with war paint. Again, accompanied by AC/DC.

Alabama quickly scored two touchdowns, after which Auburn fans sat and quietly texted each other. After another touchdown, a frustrated Auburn supporter stood up in front of me, took her blue and orange pom-pom shaker and smacked it on the railing. Once, twice, eight times, then threw it down and walked off. The game was ten minutes old.

At halftime, the score was 45-0. Thousands streamed out of the stadium. How was this supposed to be fun? Where was the suspense? I stood up and followed them. An Alabama fan named Dwight waited for a bus at the stop. I asked, “Are they going to start playing the second and third string?” He flashed the smile of the winner. “It’s so bad they’re gonna start putting in the fans soon!”

A sidewalk vendor named Eugene was selling a rack of Iron Bowl shirts. I mentioned the game was a wash. Were people still going to buy these?

“Oh, I’ll sell ‘em all,” Eugene laughed. “Alabama likes to rub it in.”

The whole thing baffled me. If you combined all of my college friends, at both Montana State University and the U of Oregon, and ran them through a strainer, you couldn’t fill three seats at a football game, much less a hundred thousand.

After such a painfully one-sided matchup, I wondered how the losers were doing. The next morning I asked the hotel desk clerk for directions to Auburn. The woman smirked and replied, “How would I know?”

I drove the 160 miles to Auburn’s campus, which gave off the distinct vibes of a post-neutron bomb attack. No signs of human life, but the buildings remained. On the day after the game, campus sidewalks were deserted, the stadium locked and empty. A lone TV news crew sat in front of the athletic building, waiting for an official statement about the football coach getting fired. In a few hours, he would be. I did find one store that was open, and it was selling a handy metal bar that read, “AUBURN.” Apparently you heated up this object on your BBQ grill and then set it on top of a hot dog, so that all of your dogs would have “AUBURN” branded into the flesh. This item seemed fantastically practical. So often when barbecuing, it’s easy to forget where you attended school.

I headed for the iconic Toomer’s Corner, a beautiful brick portal at one end of campus, where students celebrated the beginning of the Civil War and the election of Barack Obama. Two massive oak trees once stood guard, planted 130 years ago. After school victories, people would gather at the trees and toss rolls of toilet paper into the branches, creating a strange and lovely apparition of ass-wipe, streaming and flapping above the happy throng. The trees were now dead, poisoned by an idiotic Alabama fan in a highly publicized incident in 2010. Prompted, of course, by the Iron Bowl.

A retired Texas state trooper named Harvey Updyke attended that year’s game, and grew furious not only at the come-from-behind victory by Auburn, but what Auburn fans did to the Bear Bryant statue outside the Alabama stadium. As a prank, someone had draped the jersey of Auburn quarterback Cam Newton over the chest of the beloved Coach Bear. Updyke felt Auburn should be taught a lesson.

Late one night, he slunk into Toomer’s Corner, and dumped gallons of poisonous herbicide onto the tree trunks and gnarled roots. Not being the brightest bulb in Alabama, he then called into the Paul Finebaum sports radio show and bragged about his deed. Botanists and tree experts quickly descended on Toomer’s to analyze the damage and attempt to save the oaks.

Authorities soon located Updyke. Initially he admitted, “I just had too much ‘Bama in me.” But he then recanted the boast, claiming he didn’t do it, but he knew who did. Three years later he finally pleaded guilty and was ordered to pay $796,731.98 in restitution. The court set him up with monthly $100 installment payments, which he then stopped paying, prompting a warrant issued to hold him in contempt. Both schools officially agreed Updyke was a moron, but according to Alabama fans I spoke with, some still had no problem with what he did.

I walked over to Toomer’s to see if any evidence remained of this man’s stupidity. The campus entrance reeked of death. Two leafless ghosts of what were once beautiful oak trees. The branches had been sawed down to stubs. Exposed roots were discolored with black and white splotches, as if burned in a chemical fire. I stopped taking photos and put away my camera. It was just too damn sad.

Before and after photos from local news sources.

Harvey Updyke died in 2020. Replacement trees were planted in 2015. The Iron Bowl continues. So I’d now witnessed the most bitter rivalry in American sports. But it was numbing. It didn’t connect. The experience wasn’t getting me any closer to understanding why I felt this way. I would need to learn more. I would have to travel back to my hometown in southeastern Montana. All of my family members were either now dead or moved away. I had no real friends left in the area. I wasn’t sure what I was going to find. But I wasn’t looking forward to it.

To be continued.

“like a sarcastic moth” 😆🏆

Like you, I am no sports fan. Just a "man of letters" who expends my nerd energy in more classically nerdy directions--comic books, sci-fi, pop culture, punk rock, etc. But this was such an engaging piece, and I was completely caught off-guard by the left turn into dendrocide. What a piece of shit that guy was. I vocally cheered his death. Looking forward to the next chapter.