This year marks the 30th anniversary of the death of Bill Hicks, the scabrous, satirical comedian whose best material ranked right up there with Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, and Richard Pryor. My friend Paul Codiga called me up in the early ’90s and said, you’ve gotta go see this guy at the Punch Line in San Francisco. It was a singular, hilarious night. Fantastic joke-writing, but he truly didn’t care if you laughed or not. He was on some kind of mission to communicate the Great Hypocrisy. It made me think of the sound of bacon frying in a pan.

I saw him a few more times, at the Punch Line and Cobb’s Comedy Club, and we did a phone interview for The Nose. His press kit was pretty sparse at the time, I got the sense he was a teeny bit bewildered by all the sudden media attention. Although Rolling Stone named him the “hot stand-up” to watch for 1993, most of America had yet to catch on. We eventually met a few times, and I introduced him to my friend John Magnuson, director of The Lenny Bruce Performance Film, and they struck up a friendship.

He made it only to 32, but he is still revered by fans today, especially in the U.K. A documentary was released in 2009, and there are plenty of clips and memes online. The question of whether he holds up over time is valid. It was a different era. Some material can sound misogynistic or homophobic, but at the heart of it, I witnessed firsthand that he was actually a really sweet guy. A book, Love All the People (Soft Skull), and a DVD package, Bill Hicks Live (Rykodisc), were released at the end of 2004, and this piece is a overview of both. Another version first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.

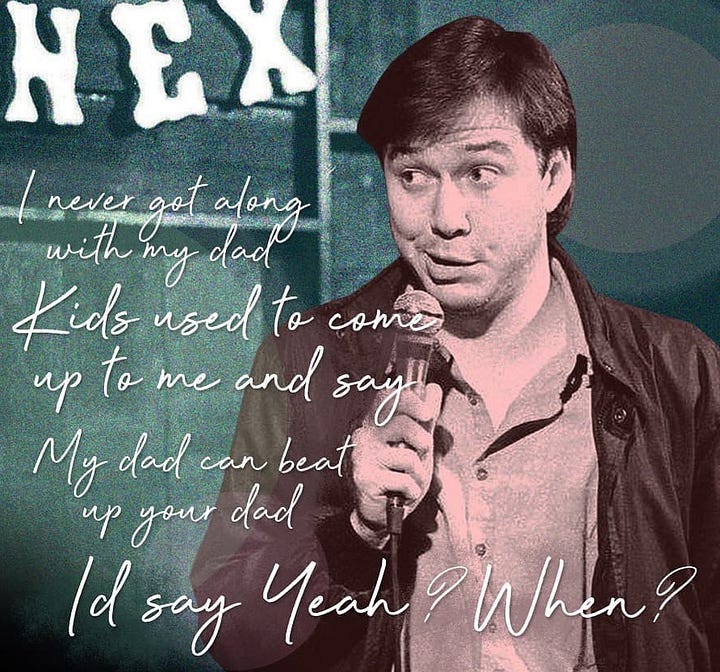

It’s always funny until someone gets hurt. Then it’s just hilarious. —Bill Hicks.

The list of Bill Hicks fans is long and varied: Richard Pryor, John Cleese, Tom Waits, Dave Chappelle, Dave Attell, Eddie Izzard, Janeane Garofalo, David Cross, Henry Rollins, Rage Against the Machine. This year marks the 10th anniversary of his death, and there are live tributes in the United States, Canada and Europe, a new book collection and a new DVD of all his major videos. Another biography and an anthology homage hit shelves next spring. All the more surprising because when Hicks died of pancreatic cancer in 1994, most of America had never heard of him.

Although he had been writing and performing for 18 years, his television exposure was minimal, and he made only two albums during his lifetime (five others were released posthumously). He had pockets of loyal fans around the United States, but much of his support came from outside the country. Such anonymity had its benefits. He could say exactly how he felt, and be completely serious, as long as it was funny:

“You know we armed Iraq. I wondered about that too. During the Persian Gulf War, those intelligence reports would come out: ‘Oh, Iraq? Incredible weapons. Incredible weapons.’

“How do you know that?

“Well. Ha ha. Ah, we looked at the receipt. But as soon as that check clears, we’re going in.”

America hasn’t changed that much in 10 years. A Bush is still in the White House, we’re still involved in a war in Iraq and our pop culture still permeates the planet, just substitute Paris Hilton for Madonna. But that Hicks’ popularity has only grown speaks both to timelessness and to necessity. What would he think of today’s news? People around the world seem to be begging for his scalding view of politics and the international chaos that came after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks.

Bill Hicks started writing jokes as a young teenager, sitting in his suburban bedroom in Houston, taping Johnny Carson and other comedians on television. Forbidden by his parents to perform in clubs, he sneaked out the window, climbed down a drainpipe and met his friends to drive to Houston’s comedy mecca, the Comedy Workshop. By the time he finished high school, he was already a headliner, attracting a line down the block.

In the 1980s, comedy became rock & roll. Every shopping mall and sports bar in America featured some form of comedy entertainment. Most of these performers are now long forgotten, immortalized in yellowed head shots with wacky-funny poses and skinny neckties, which you can still see tacked to the walls of some clubs. The phenomenon made room for some brilliant comic minds, and a lot of dreck. Hicks survived the comedy boom, and he even gave up a reckless drugs-and-booze lifestyle.

Newly sober, his performances grew exhilarating and scary, wrapping poetically absurd concepts in vivid language, with razor timing. He made you either fall out of your chair laughing or walk out of the room. You had to be willing to meet him halfway because he drove the rest of the journey. Audiences expecting jokes about airline food were shocked to hear informed rants on politics, drugs, sex, war and fundamentalism.

His caustic riffs on religion in particular resonated with crowds. Growing up in a strict Baptist household, Hicks had firsthand experience with Christian beliefs, and his delivery and passion echoed the energy of a Southern preacher. He realized that in puritanical America, religion is the ultimate taboo, and therefore an obvious target:

“I’ve always found religion to be fascinating. Ideas such as how people act on their beliefs. Pro-lifers murdering doctors. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha! Pro-lifers murdering people. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha! You know, it’s irony on a base level, but I like it. It’s real basic irony, but still you can get a hoot... You’re so pro-life, do me a fucking favor. Don’t block med clinics, okay? Lock arms, and block cemeteries. Let’s see how fucking committed you are to this premise…”

“We had to bust the [Branch Davidian] compound down ’cause we heard child molestation was goin’ on.”

“Yeah, if that’s true, how come we don’t see Bradley tanks knocking down Catholic churches? I’m talking if child molestation is actually your concern.”

Hicks liked nothing more than to make audiences uncomfortable. Let me rephrase that: He went out of his way to make people fidget in their seats. He appeared not to care one bit about the crowd reaction, but in a deeper sense, that was all he cared about. His comedy came from a completely unique source, revolving around the hope of who we as human beings could become, versus the frustration of who we are. To Hicks, we were “the facilitators of our own creative evolution.” He was evolving toward enlightenment, and he wanted everyone to evolve with him:

“The world is like a ride in an amusement park. And when you choose to go on it, you think it’s real because that’s how powerful our minds are. And the ride goes up and down and round and round. It has thrills and chills and it’s very brightly colored and it’s very loud and it’s fun, for a while. Some people have been on the ride for a long time and they begin to question—‘Is this real, or is this just a ride?’ And other people have remembered, and they come back to us, they say, ‘Hey, don’t worry, don’t be afraid, ever, because this is just a ride.’ And we…kill those people.”

He kept up a grueling schedule, often doing as many as 300 gigs a year. He turned down offers to do commercials, refusing to do anything except on his own terms. This meant he would fill 3,000-seat theaters in England and then return to the United States to perform in front of a hundred drunks in a nightclub.

As with any writer, travel abroad affected his material by making it easier to observe America’s shortcomings. From growing up in such a self-absorbed, confident country, it must have been refreshing for him to perform in Britain, where wit and sarcasm are a natural outgrowth of personal loathing. How must it feel, hearing Brits roar with laughter at the same material that wasn’t appreciated in the land of his birth:

“There ain’t no fucking deficit, it’s a fucking lie and it’s a fucking illusion in the first place. But you wanna end it, you wanna end it, legalize pot: biggest cash crop in America. Deficit’s gone. But I am so sick of hearing about, ‘Well, your leaders misspent your hard-earned tax dollars, so you the people, now have to tighten your belts…because we, your leaders, misspent your money.’ You know what would make tightening my belt a little easier? If I could tighten it around Jesse Helms’s scrawny little chicken-neck…I’d tighten my belt if that were the case. I’d eat bologna for a week…I’d sacrifice.”

One of Hicks’ recurring targets was the continual disappointment of American show business, where mediocrity rose to the top and permeated our brains like a virus. Musicians like Billy Ray Cyrus and New Kids on the Block, personalities like Arsenio Hall, Rush Limbaugh and Jay Leno. To Hicks, these weren’t famous and talented people, they were “fevered egos tainting our collective unconscious.”

Leno was a surprise choice. No comedian would dare make fun of the Tonight Show host, if there was a chance they could be a guest on the show. Hicks simply didn’t care. To him, it was more important to point out that Leno was once a great comedian—who had actually helped Bill get his first booking on the Late Show With David Letterman—and had sold his soul to the devil in order to chat up celebrities and be a pitchman for Doritos, “selling snacks to bovine America.”

Hicks and his friends created a betting pool to guess which lame showbiz guest would be on the program on the night Jay finally snapped and committed suicide: Joey Lawrence or Patrick Duffy. He delivered the bit in an uncanny dead-on Leno impression:

“Jay: Oh, hi everyone, welcome to the show. Tonight we have Joey Lawrence. Hi, Joey, how are you? It’s good to see you again. Boy, it was always my comedic dream to be forty-four years old and be interviewing a little Tony Danza wannabe every three months. Boy, I’m fulfilled as a human spiritually. So anyway, Joey, you’re sixteen now, you’re sixteen years old?

“Joey: Yeah.

“Jay: That’s great, you’re 16. You got a license? You drivin’? You drivin’?

“Joey: Yeah.

“Jay: That’s great. You’re 16, you got a license. You got a car? You got a car?

“Joey: Yeah.

“Jay: You got a girlfriend, hmm? You dating somebody? Anybody special?

“Joey: Yeah. No. Well, she thinks so, I don’t. Hee hee hee hee.

“Jay: Good God, what have I done with my life?”

[Hicks mimes putting a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger with a loud explosion]

Hicks: “His brains blew out, forming an NBC peacock on the wall behind him. Because he’s a company man to the bitter fucking end.”

Well, maybe you have to hear the recording. I’m not even going to go into detail about Satan having sex with Leno while he’s doing a Doritos commercial. This is a family newspaper, after all.

Love All the People: Letters, Lyrics, Routines collects a trove of material for fans: transcripts of live shows, essays and interviews, song lyrics and articles written for magazines, with a forward by John Lahr of The New Yorker. The compilation is scattershot and jumps around in time, but it does flesh out what has become a watershed moment in the Hicks legend.

On Oct. 1, 1993, his 12th appearance on Letterman was edited out of the show before broadcast. It contained a version of this bit:

“Well folks, this is kind is a sentimental evening for me…this is my final performance ever. No biggie, no, no, no, no, no hard feelings, No sour grapes whatsoever. I’ve been doing this sixteen years, enjoyed every second of it. Every plane flight, every delay, every lost luggage, living in hotel rooms, every broken relationship, playing the Comedy Pouch in Possum Ridge, Arkansas every fucking year. It’s been great. Don’t get me wrong. But the fact of the matter is, the reason I’m gonna quit performing is I finally got my own TV show coming out next fall on CBS. So…thank you. I know. It’s not a talk show. Dear God, thank you, thank Jesus, thank Buddha, thank Mohammad, thank Allah, thank Krishna, thank every fucking god in the book. No, it’s not a talk show. It’s a half-hour weekly show that I will host, entitled Let’s Hunt and Kill Billy Ray Cyrus. So ya’ll be tuning in? Cool. It’s a fairly self-explanatory plot. Each week we let the hounds of hell loose and we chase that jar-head, no-talent, cracker asshole all over the globe…’till I finally catch that fruity little pony tail of his in the back, pull him to his knees, put a shotgun in his mouth, ‘POW!’ And we'll be back in ’95 with Let’s Hunt and Kill Michael Bolton. So…Thank you very much. I’m just trying to rid the world of all these fevered egos that are tainting our collective unconscious and making us pay a higher cosmic price than we can imagine.”

After discovering he’d been censored—the show had initially okay’d all of his material—Hicks wrote a 31-page handwritten letter to Lahr. It’s a heartfelt document describing his struggle with the American entertainment machine, all the more wrenching because he was already dying of cancer.

As his health deteriorated, we see the comedian wanting to make peace with the world. A few months before his death, he sends handwritten Christmas letters to both Letterman and Leno:

“Jay…These things are not said in ‘hate,’ nor said by ‘enemies.’ It’s more or less like how we all will ‘run down’ our own best friend (or even ourselves at times). ‘You know what Mark needs to do is...’ etc., etc. These statements are done from a concerned and interested party. Not an ‘enemy.’ It is in fact a sign of how much an influence you’ve played in my life, this interest and intriguing kind of questions. I hope you don’t take it personally, or seriously. Your friend, Bill Hicks”

The DVD Bill Hicks Live: Satirist, Social Critic, Stand-Up Comedian includes three filmed performances, from the Old Vic Theatre in Chicago, London’s Dominion Theatre and the Montreal Comedy Festival. This is vintage Hicks material, captured in full scream, with the harshest moments followed by the perfectly timed: “I am available for children’s parties, by the way.” A bonus documentary, Just a Ride, includes thoughts and memories from Brett Butler, Eric Bogosian, Richard Belzer, Leno and Letterman, among others.

In 1991, I interviewed Hicks, and asked what he thought was funny. “I just have this weird theory,” he said. “The best kind of comedy to me is when you make people laugh at things they’ve never laughed at, and also take a light into the darkened corners of people’s minds, and expose them to the light. I always felt that’s what the point of it all was, to make you feel un-alone. Many thoughts I do have are not my own thoughts. You know what I mean? They’re not secret thoughts.”

We talked about sacred cows, and he read me a letter from an upset audience member who had complained to a club owner. I asked him about going too far with an audience. “Yeah, there’s been a lot of those, but it’s never been because of the material. It’s been more because of my attitude doing it. That’s my biggest problem—my attitude. I don’t think material-wise you can go too far. You can pretty much tiptoe through a minefield if you just make sure you step real lightly.”

He looked forward to making a lot of money and getting out of the business forever. “I’d like to be more like the J.D. Salinger of comedy. I’d like to produce one book that every year 30 million people buy again.”

Ten years after his death, Hicks finally has a book, a catalog of audio and video recordings, and a place on the Satirist Shelf alongside Lenny Bruce. It won’t sell 30 million copies, but that’s okay. It was always more about quality than quantity.

Arizona Bay.