Terry Southern: The Dexed Tex

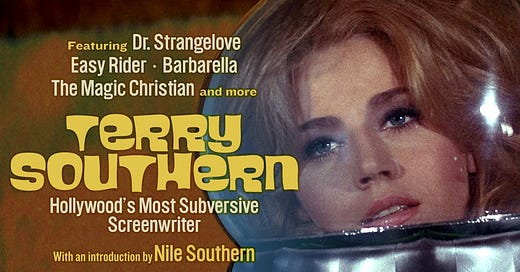

Hollywood's most subversive screenwriter is now featured on Criterion

This month the Criterion Collection just shared a new cluster of films called Terry Southern: Hollywood’s Most Subversive Screenwriter. And it warms my heart to realize that some people will be discovering his work for the very first time.

From the late ’50s through the ’60s, Terry Southern experienced an unprecedented burst of creative success, publishing the novels Candy, The Magic Christian and Blue Movie, as well as cranking out scripts for the films Dr. Strangelove, Easy Rider, Barbarella, The Loved One and The Cincinnati Kid. In the midst of a culture struggling with A-bomb paranoia, racism, drugs and the sexual revolution, the Texan’s outrageous, often shocking satire disguised as credible realism was a perfect fit for the era.

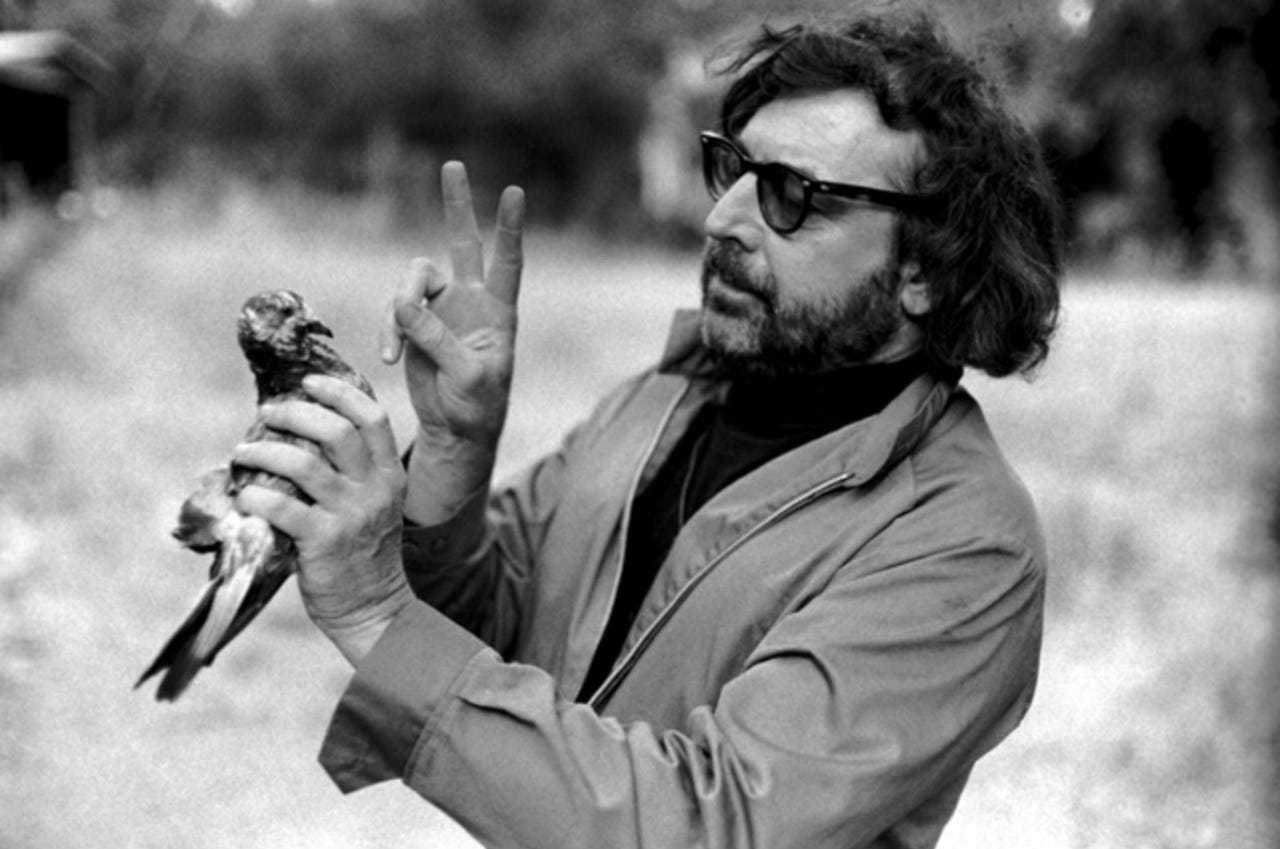

In the 1990s I grew obsessed with Terry Southern, renting the films and digging in used bookstores to track down the novels. There was a fair amount to unearth. (Another indispensable read was Red Dirt Marijuana, a late-60s collection of short pieces and New Journalism, which Joseph Heller called “the cutting edge of black comedy.”) Southern was sort of a counterculture Zelig. He seemed to always hover about the zeitgeist and be in the right spot at the right time. He socialized with writers who launched The Paris Review. He appeared on the Sgt. Pepper’s album cover, and in the Stones documentary Cocksucker Blues. He dodged police clubs with Ginsberg and Burroughs at the ‘68 Chicago convention protests. He worked with Hustler publisher Larry Flynt. And he contributed to National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live. Stumbling upon this weird and hilarious writer, from an earlier period, was similar to discovering the dark 1930s satire of Nathanael West’s novels like Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust. But how on earth did these guys ever get published? Because they were geniuses, and reading rebellious entertainment is still not a crime. At least not yet.

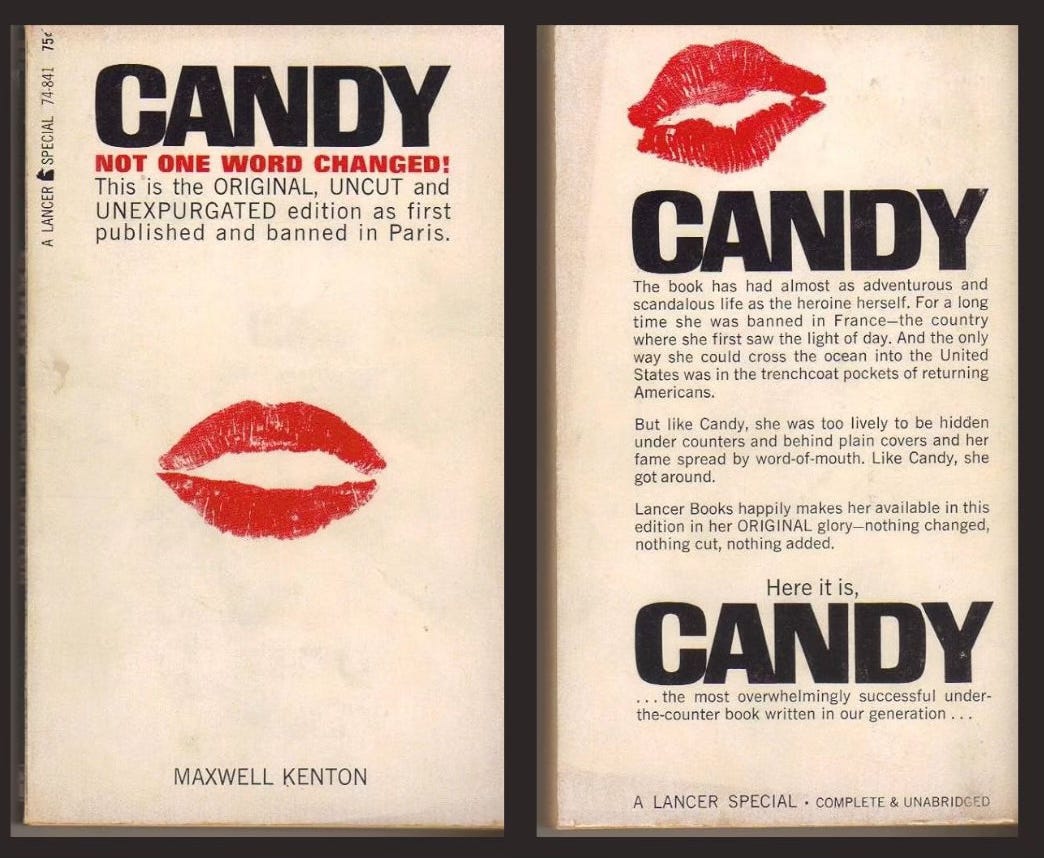

Southern’s films range from exquisite (Dr. Strangelove) to hippie-messy (The Magic Christian) but he should be remembered above all else for the novel Candy. Its origins were so preposterous, his son Nile Southern wrote an entire book, The Candy Men, solely about it. In the 1950s, two American expat hipsters bounced around Europe, on the fringes of the lit scene. Southern and his friend Mason Hoffenberg proposed to co-write a sexy humor novel, and set it in Greenwich Village. They were living in different countries at the time, so they mailed each other chapters, sharing jokes back and forth. Paris-based Olympia Press. which specialized in outré writers like Nabokov and Henry Miller, agreed to publish Candy, and paid the authors either $300 or $500 each. The book quickly gained a reputation as scandalous and extremely funny, and was rapidly bootlegged, selling millions of copies. (Some even suggested it was inspired by Voltaire’s Candide.) But Candy’s story was so frank and sexually explicit, Southern and Hoffenberg initially chose not to use their real names. Early editions instead listed the author as “Maxwell Kenton,” and his phony bio is so perfect I’m reprinting it here:

Maxwell Kenton is the pen name of an American nuclear physicist, formerly prominent in atomic research and development who, in February 1957, resigned his post, “because I found the work becoming more and more philosophically untenable,” and has since devoted himself fully to creative writing…The author has chosen to use a pen name because, in his own words again, “I’m afraid my literary inclinations may prove a bit too romantic, at least in their present form, to the tastes of many of my old friends and colleagues.”

This present novel, Candy—which, aside from technical treatises, is Mr. Kenton’s first published work—was seen by several English and American publishers, among whom it received wide private admiration, but ultimate rejection due to its highly “Rabelaisian” wit and flavor. It is undoubtedly a work of very real merit—strikingly individualist and most engagingly humorous. Perhaps it may be said that Mr. Kenton has brought to bear on his new vocation the same creative talent and originality which so distinguished him in the field he deserted. And surely here is an instance where Science’s loss is Art’s gain.

I could go on and on, but we need to keep things tight and get to the interview below. So read the books, watch the films. Sadly, apart from the muddled ’80s movie The Telephone, no script was produced in his final 25 years. In 1995 Terry Southern collapsed on the campus of Columbia University, where he taught screenwriting, and died four days later at the age of 71. Among his final words was the prophetic, “What’s the delay?”

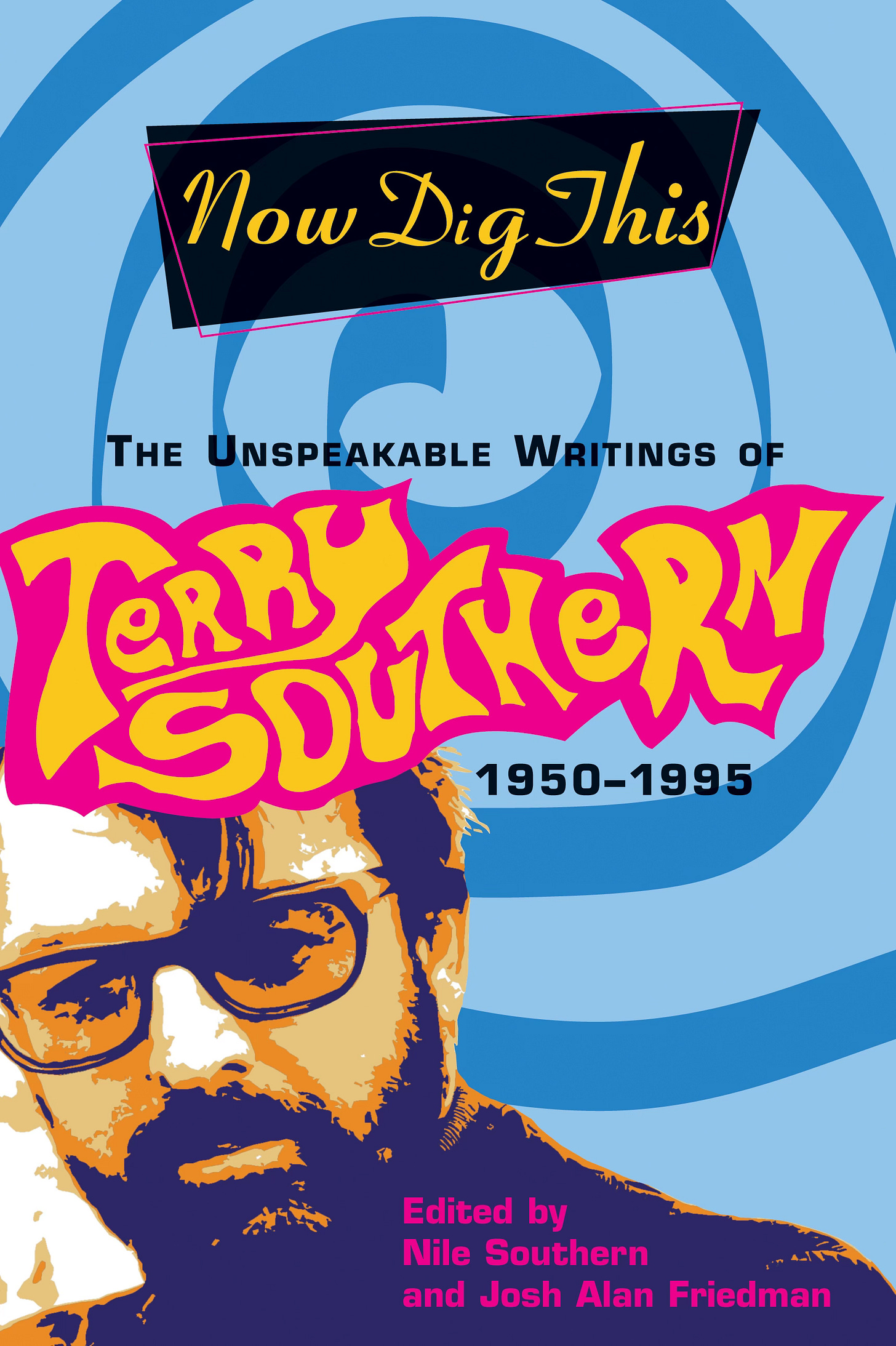

Nile Southern is the estate’s executor, and for years has been enmeshed in running his father’s literary estate, from a biography, to a documentary in progress, and a website filled with tidbits. There is now plenty of Terry Southern to explore. One of the first posthumous releases was the anthology Now Dig This, which compiles nearly half a century’s worth of Southern’s literary reviews and essays, scenarios and sketches, and a handful of absolutely ludicrous personal letters that are worth the read all by themselves. Upon its release in 2001, I interviewed Nile Southern about the book and his dad. This originally appeared in New York Press.

How did the Now Dig This compilation come about?

I started a new collection of my dad’s work when I was in high school. I’d leave little typed notes for him, saying, “Attention, TS,” and suggest he delete or add to the titles on the list. He’d just toss it aside—didn’t care to market himself or call attention to himself. I think Terry expected some brilliant literary swordsman to come in and just do it. Then I bought a laptop and spent my days plotting out the wholesale Terry Southern takeover of America. In a honeymoon cabin the night before my wedding, I’m there until the wee hours of the morning hrrrrrr, hrrrrrr, hrrrrr, hrrrrr printing out the entire “Terry Southern Book Project Proposal,” which outlined everything: collected screenplays, letters, anthology, scrapbook, essays, pasted pictures throughout. The whole tome was given short shrift by Quality Lit City—I can tell you.

Years later, after Terry died, I started talking with Josh Alan [Friedman] about the project. As Esquire said, Terry is “the writer most capable of handling frenzy on a gigantic scale,” but Josh is probably the editor most capable of cutting it down into manageable chunks. It was about 500 pages. We cut it down to about half that. Anyone who knows Terry’s work is probably aware of a certain multifacetedness. And that, I think is one of the attractions—especially now, when “writer” can mean everything from “Internet artist” to midlist failure. So the unspoken impulse in trying to sum up Terry is to show the range of literary expression (besides poetry) emerging out of the postwar American period, and into the new first-person terrain of the mid-60s-90s.

Any favorites that didn’t end up in the anthology?

A three-page setpiece, a “scenario for existing props and French cat.” Terry’s ghostwriting of Larry Flynt’s full-page New York Times diatribe about the downing of KAL 007. His piece about “The Dawn of Cornhole,” where early pilgrims would come back from the field with a corn husk “just oozin’ with fresh jissum!” A response to a form letter from Moneysworth magazine asking, “What’s the most extravagant purchase you ever made?”—to which Terry replied, in extravagant detail, a $14,000 blowjob from Rita Moreno (“not the Rita Moreno, but someone claiming to be Rita Moreno…”)—also didn’t make the cut.

It’s a huge responsibility, to comb his archives and put his work back out there for people. Did you anticipate you’d be in the business of keeping your father’s name alive?

Actually, I anticipated inheriting the most beautiful farmhouse in the Berkshires—he always said I would have it—but he left so much debt behind that the house is now relegated to dreamland. I won’t let that happen to his intellectual properties. There is no reason why they cannot bring in respectable amounts of money for his grandchildren. If Terry were a hack, or some kind of bullshit “entertainer,” or a lightweight panderer to either film or book publishing, I would certainly walk away from it or farm it out. But he was someone who really was writing from a place of profound amazement at how corrupt our government is, and how hypocritical and shallow the money-culture is. This is a sentiment that is important to keep alive in perpetuity.

Obviously, I’m of a completely different generation. For him, the standards were Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Fellini, Lenny Bruce, French New Wave. For me, my standards were/are more like Brian Eno, Negativland, Bongwater, Asian underground, Derek Pell, Democracy Now!, Michael Parenti, Craig Baldwin. But this whole process of “working with Terry” is rooted in the ongoing struggle in our contemporary culture of liberating subversive thoughts and offering critiques of what’s happening, through both profound exaggeration and sublime, succinct insight. So, this impulse which we share is certainly worth pursuing, whether it is my own work or his.

How was he able to appeal to and circulate within such a prominent, fast-paced crowd of rock musicians, artists, writers and Hollywood rebels?

I think he kind of absorbed the aspects of his peers and idols, and incorporated their behaviors into his own. He was very much an amalgamation of all that was hip and wonderful in his time. He was also this big, gentle, bear-like man of British-like style and grace—a gentleman first and foremost, but one with a gleam in his eye that would not stop twinkling. He also had this heavy-duty hipster side to him that was full blown in the mid-’60s, total slack bemusement charged up with amphetamines—and barbiturates, too (dexamyl)—so that the result was a kind of snarling mock astonishment, and then he’d lay it on the line.

Many writers and filmmakers cite him as an influence. Where does the Southern legacy manifest in today’s Hollywood?

I think you find it in the more educated mavericks who have always thought for themselves: the Soderberghs, Jewisons, Haskell Wexlers. There are always people in Hollywood interested in seeing what they can do that is “Terry.” The problem often is that the people who come forth—like many of the spec people who approached Terry during the last 30 years of his life—simply don’t have the chops. A producer or director might think, “We’re doing a Terry Southern-type thing,” and then when you look at what they’ve got, it is absolute rubbish. Innovation is often too crippling a quality for those whose careers are tied to corporations striving to imitate, imitate, imitate 24-7. To do Terry, you have to give into it 100 percent. Otherwise, as he used to say, “You’re doomed!”

The topic of sex infuses all his best work—from essays and novels to the “precious bodily fluids” of Dr. Strangelove. Why did he write so much about sex?

He loved women, and despite what some people may think on the surface, his prose and dialogue are really very empowering. He was trying to destigmatize certain words like “clit” and concepts like “deep vag pen.” And I think the impulse was to shake things up—so that we can speak joyously of these things without unspoken fear and prejudices, but also because by having characters speak these words, we get to watch their unraveling of the taboo in real time.

Terry was very sensitive to the differences between Americans and Europeans concerning sex, and often referred to these—such as the “5-7” term in France, referring to the “tradition” of a man having sex with his mistress after work. The fundamentalist prudishness and puritanism found in the States is still something worth blasting. Even in his day, commercial media had made a play to corner the minds of people concerning sex, and had reduced it to fit their own agenda of simply owning your brain. That is such a despicable waste of our greatest natural resource—our own sexuality—and to have it toyed with and shaped by commercial advertisers is something Terry was also addressing.

People are now aware that Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper refused to give Terry any percentage on the millions that Easy Rider grossed, even though he contributed to the script and supplied the title. Have you heard any reaction from either Fonda or Hopper?

Apparently Fonda’s been advised not to receive my letters anymore, but I believe he will come around, karmically. He or his wife got all upset about a newspaper article that came out in the L.A. New Times that I really had no control over. As for Hopper, well, he’s a Republican. A Palestinian filmmaker I know watched Hopper with horror at the Rotterdam film festival during the Gulf War, when he was cheering, “Bush! Bush!”

You’ve written about hanging out and partying with Hopper. He could have made your father’s life much easier, financially. Sounds like a tricky situation. How did you deal with it?

At the time, I was not really aware of the backstory, and Terry was never one to moan about or even reveal anything. Here’s a guy who had cancer, a stroke, fucking IRS coming down on his house—and he didn’t mutter a word. I think he felt that complaining was simply a sign of total self-involvement and that people need to look outward. But Terry held no grudge against anyone, no matter how severe the trespass. He was into the creative back and forth, the exchange of energies, and he liked extreme people like Hopper. I think his impulse was to say, “God, if I could only give this guy some killer lines, this interesting film idea he’s so worked up about could really zing…” It was not until Hopper/Fonda tried to get Terry to relinquish Terry’s “interest” in Easy Rider that Terry felt totally offended and started speaking his mind, the highlight of which was, “They can’t write a fucking letter.”

What’s it like growing up as the son of Terry Southern? Did he encourage you to be a writer?

I have tapes of him questioning why, as a four-year-old, I liked to sing “Old MacDonald.” He encouraged me to sing “Pop Goes the Weasel” instead. He was very particular about what was good entertainment—so I developed a pretty refined sensibility by age eight. He was a little disappointed that I was writing, although he did encourage me. His advice was always to “go as far out as you can” without blowing your “credibility”—both storywise and in your author-voice. But he always felt that being a film director was the ideal occupation—and that the writer always gets shat upon. He also encouraged me to be a ski-bum piano player.

Is it too late to be a ski-bum piano player? Because I’m in. Niles is wonderful. He asked me to narrate his dad’s “Blue Movie” for the audiobook, which as an actor I didn’t deserve, but god, I loved the book and I was determined to make my “Teeny Marie” count. Like you, Jack, I started with Red Dirt Marijuana and it just got better.

Yayyyyyy for the Criterion deal. It’s about time.

I got regaled with a few choice stories of editorial work between Terry & Lee Quarnstrom when they were at Hustler, basically using it as a platform for all types of subversive screeds with Larry’s blessing at the time…