Snatching Saroyan

The academic battle over the archives of San Francisco’s most prolific author

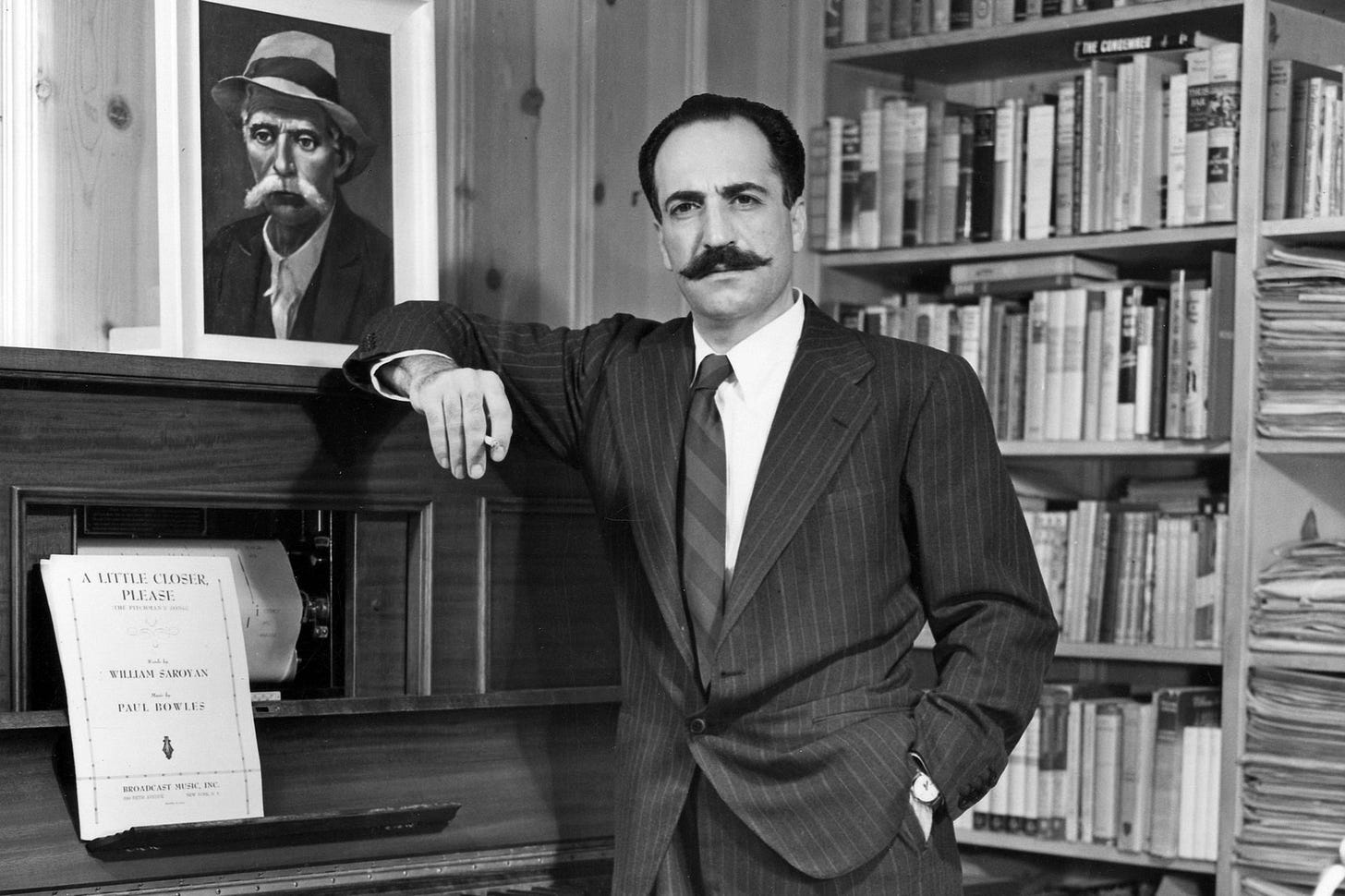

William Saroyan, Paris, 1973

Hi there, this piece of journalism dates back some years, and there’s no real reason to share it now, but it’s been on my mind lately, so I thought I would post it anyway. I was drawn to it for several reasons. It’s the incredible tale of William Saroyan, a California writer who won both a Pulitzer and an Oscar (he refused the former, and the Oscar statue later ended up in a San Francisco pawn shop). You have a writer who was clearly obsessive, claiming to have written over 500 stories from 1935 to 1940. He was what we now call a hoarder, and quite possibly undiagnosed with mental issues. You have a bitter academic clash between Bay Area universities over his literary archive. And the resulting bad taste in one’s mouth from learning how opportunists fight over the carcass of a dead writer who deserved better.

He passed away in 1981, but man oh man, William Saroyan is far from forgotten. U.C. Berkeley’s Armenian Studies Program is still supported by the William Saroyan Endowment. Stanford’s William Saroyan International Prize for Writing is funded by The William Saroyan Foundation, which also funds the Saroyan/Paul Human Rights Playwriting Prize. In 2012 Saroyan family members filed official status for Forever Saroyan LLC, an online archive. In 2018 Saroyan’s home in Fresno opened as the Saroyan House Museum, featuring “the world's largest digital archive of Saroyan.” In 2019 a new Saroyan documentary premiered, Lights! Camera! Saroyan! His son Aram and granddaughter Strawberry are both writers. And I just can’t get over the fact that in 1939, William Saroyan wrote a play in a hotel room in SIX DAYS, set in a San Francisco saloon, and it won BOTH the Pulitzer and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. If you’re a writer, there’s a benchmark to consider.

This article originally appeared as the cover story of SF Weekly in 1998.

In the fourth-floor bar of the exclusive University Club building atop Nob Hill, the Roxburghe Club, a San Francisco organization of rare book aficionados that dates back 70 years, prepares to begin its monthly meeting. Membership in the club is limited to 100 people, many of whom are currently meandering underneath a wooden oar labeled “Harvard/Yale.” It is a highbrow crowd of librarians, book dealers, collectors, fine printers, primarily elderly old-money males but a few women, one of whom wears a bright red raincoat.

Against the ever-growing behemoth of electronic media, these true lovers of books steadfastly cling to the centuries-old world of movable type, the feel of an ornate font pressed into thick paper, the way the gold leaf of a first-edition cover glints under the light. Conversation drifts about and around Maxfield Parrish collectibles and estate sales in Hillsborough.

Eventually, guests hobble down a flight of stairs to the dining room, where the Roxburghe Club’s George Fox has taken the podium. Standing in front of picture windows that reveal the Financial District dropping away in the misting blackness, the “Master of the Press” offers a toast to a member who recently passed away. Wine glasses raise from all tables. Everyone starts sawing through steak. Fox begins to introduce the scheduled after-dinner speaker, William McPheron, Stanford University’s curator for English and American literature. His topic: “Beyond the Headlines: The William Saroyan and Allen Ginsberg Archives at Stanford.”

Fox points out that these two recent and prominent additions to Stanford have garnered somewhat sensational news coverage. The media, for instance, have focused on the eccentric items each author kept—Saroyan's boxfuls of rubber bands, used kleenex, and rocks; Ginsberg's personal stashes of dirty sneakers and pubic hair—rather than the creative processes they employed. Buttressed in the front row by a table of his Stanford colleagues, McPheron takes the podium to put out this small academic brush fire.

In a quiet voice, he begins a breezy summation of Saroyan’s career, recounting minor creative epiphanies (“At 3:25 on the following morning, Saroyan reaches a very different conclusion”) and offering quick, digestible nuggets of analysis (“His revisions point to the dedicated modernist, for whom style is vision”). McPheron clicks through the slides, images of typed documents with letters so tiny they are completely invisible from the back of the room.

It doesn’t matter, for at least 25 percent of those in attendance at the Roxburghe Club are dozing. Some hide their faces in their hands, others let chins fall to chests, and a few heads sway lazily forward and back, as if bobbing in the ocean of McPheron’s cool emotionless connections and conclusions.

McPheron turns to Ginsberg’s unity of effect, and the juxtaposition of his poetic concern and his public image, and “the thematic armature on which Ginsberg builds,” until one man, a fine printer by trade, suddenly exclaims rather loudly, “Oh, bullshit!”

The Ginsberg and Saroyan collections have something in common other than status as source material for dull lectures. They both recently arrived at Stanford from long-term housing in libraries of other universities. Stanford bought portions of Ginsberg's archives from his alma mater, Columbia University. What was not owned by Columbia outright, Ginsberg sold to Stanford before his death, receiving an estimated $1.4 million.

The situation at Berkeley was more controversial. Portions of Saroyan’s papers had been on deposit at U.C. for nearly 30 years, but in April 1996, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library suddenly received a letter from the William Saroyan Foundation, trustee of the writer’s estate and owner of the Saroyan collection.

The library, the letter instructed, was to immediately relinquish all Saroyan materials to Stanford.

Simultaneously, the foundation signed over all rights to and copyrights of Saroyan’s works directly to Stanford University. Included in the archives are several hundred plays and short stories, journals, and correspondence, much of it never published. The book and library communities were abuzz with gossip. The Saroyan papers represented one of the largest single-author literary collections in the United States.

The papers and publication rights connected to them are probably worth millions. The foundation charged with managing the collection all but gave it away to Stanford, which acquired a genuinely prestigious academic feather-in-the-cap—without paying one red cent.

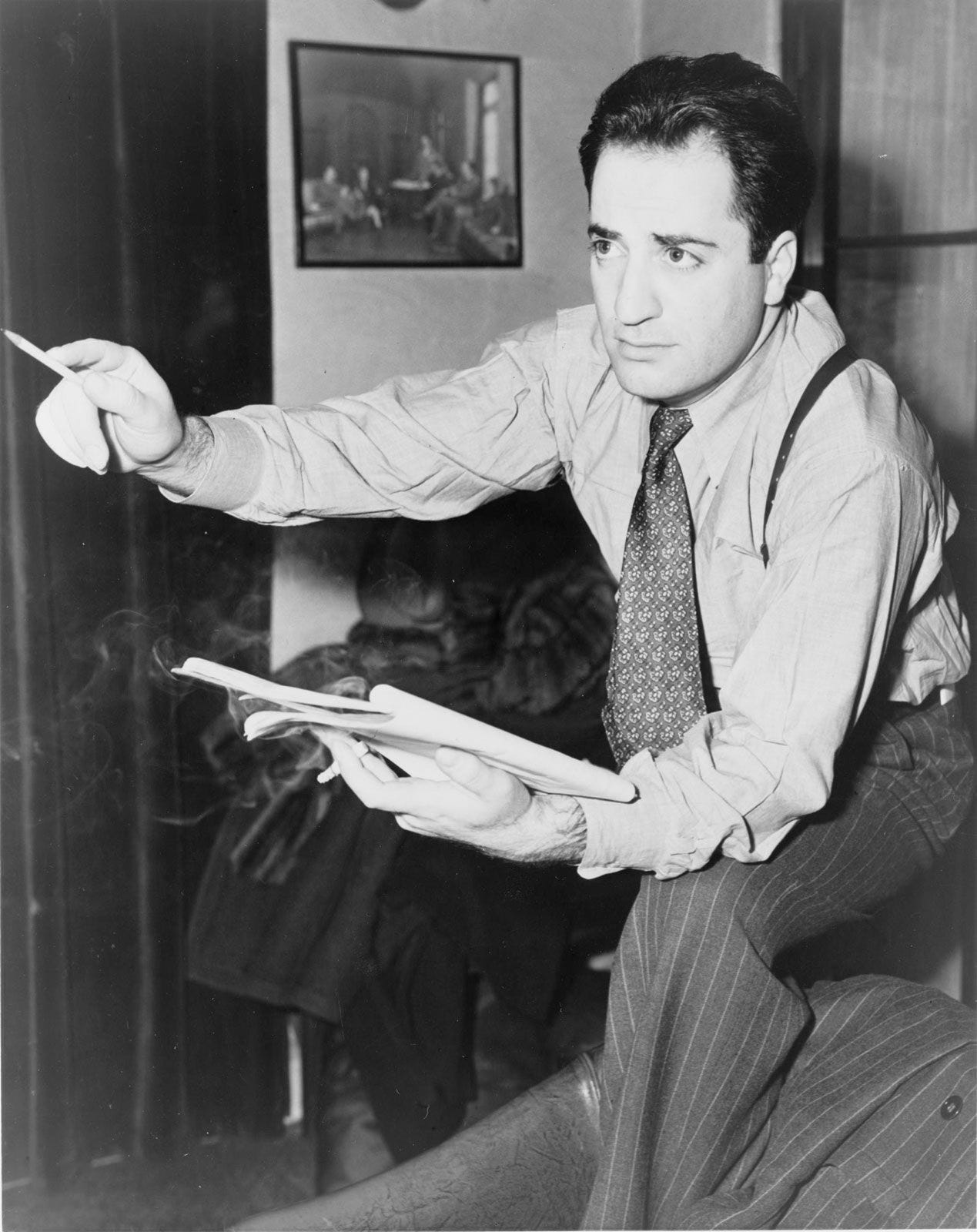

Born in Fresno to Armenian immigrant parents in 1908, William Saroyan had a chaotic and confrontational early youth. His father abruptly died when he was only 3, and his mother placed him and his siblings in an Oakland orphanage for the next five years. Driven to become a writer, Saroyan dropped out of high school to move in with family in San Francisco, where he unsuccessfully attempted to peddle his writing, enduring the ridicule of relatives who thought him a no-good bum.

His breakthrough story, “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze,” was published in Story magazine in 1934, while Saroyan lived as a young, impoverished writer on Carl Street. The tale followed the life of a young, impoverished writer who lives on Carl Street and wanders the streets of San Francisco, unable to sell any of his work:

“I’ll go and sleep some more, he said; there is nothing else to do. He knew now that he was much too tired and weak to deceive himself about being all right, and yet his mind seemed somehow still lithe and alert. It, as if it were a separate entity, persisted in articulating impertinent pleasantries about his very real physical suffering. He reached his room early in the afternoon and immediately prepared coffee on the small gas range. There was no milk in the can and the half pound of sugar he had purchased a week before was all gone; he drank a cup of the hot black fluid, sitting on his bed and smiling.”

With only a final penny to his name, the narrator lies down on his bed and dies with a smile. Both sad and ultimately uplifting, the story was an immediate success, and many more followed, published first in periodicals and then collected into books. At 26, he was already famous, an eloquently simple voice of prewar America, telling stories of hardships and survivors, of immigrants hustling to make ends meet, and scrambling to support their families.

Saroyan would best be known for two monumental successes. A six-day marathon typing session in a hotel room produced a play called “The Time of Your Life,” based on real-life characters from a saloon named Izzy’s on San Francisco’s Pacific Street. The play went to Broadway and won the Pulitzer Prize for drama, which he publicly refused, saying, “Art must be democratic, but at the same time it must be both proud and aloof. It must not be taken in by either praise or criticism.”

“The Time of Your Life,” 1939 Broadway production, featuring Gene Kelly (center)

His other major career triumph came with The Human Comedy, a screen story eventually reworked into a screenplay and film, for which he won an Oscar for best original story in 1943, and which starred Mickey Rooney and Robert Mitchum. Its sentimental depiction of a small California town during World War II resonated strongly with a patriotic nation already experiencing the tragedy of mass casualties, and his own adaptation into a novel became a bestseller. Unfortunately, after a dispute with the movie studio over being allowed to direct the film, he angrily sold his interest for a flat fee, and never again worked with Hollywood.

Continued literary success, however, guaranteed him a regular table at the Stork Club in Manhattan, and for a time he wrote and produced plays at his own theater house there called the Belasco. He co-wrote a hit song for Rosemary Clooney called “Come On-A My House,” and caroused the party circuit with Artie Shaw. Visits to San Francisco were usually marked by the obligatory item in Herb Caen’s column. The word “Saroyan-esque,” meaning sweet and eccentric, entered the nation’s vocabulary. He referred to himself, only partly in jest, as “the most famous writer in the world.”

A marriage to Carol Marcus, a blond debutante (he was 35, she was 17), would produce two children, no doubt a dream come true for a writer whose work captured the spirit and innocence of childhood. Unfortunately, the union ended in a nasty divorce. The Saroyans reconciled and married again, but it didn’t work. Marcus would wed actor Walter Matthau. William Saroyan, obviously heartbroken, would never seriously consider marriage again the rest of his life.

After the split, Saroyan’s writing grew even more self-obsessed. Pages of his manuscripts were marked with the exact time he began and finished typing. He saved every moment of his life, obsessively writing stories and plays that were never meant to be read, recording himself listening to the radio, and collecting rocks, transit receipts, fingernail clippings, and sacks of rubber bands.

“Other friends collected money,” explains his niece, Jacqueline Kazarian. “He collected rubber bands, to show them it was a game. The rubber bands were as worthless as the money.”

Stories continued to flow from his typewriter—books for children, memoirs of Fresno, warm reminiscences of family life that ran in earnest magazines like The Saturday Evening Post. But some believe the heartfelt tone was an artful disguise.

“He had developed a kind of genial voice that made him seem as though he was all-knowledgeable and had a whimsical attitude towards the crazy world,” says John Leggett, who has spent 10 years writing a still-unpublished Saroyan biography. “In fact, he was really an angry, bitter man. In real life, he disliked most people. He had very few friends, if any. His friends were all his relations.”

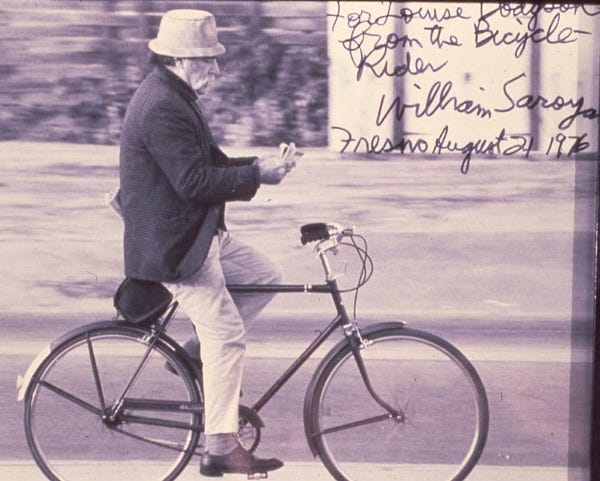

A long-standing fondness for both drinking and gambling guaranteed Saroyan a roller-coaster income most of his life, and persistent income-tax problems led him to alternate residence between Fresno and Paris. He typed, listened to music, and rode his bicycle through the streets, the picture of both bohemian eccentricity and eternal loneliness.

Compounding his problems, by some accounts, were his son, Aram, and daughter, Lucy, who were raised primarily by their mother. Aram, a writer who once received a $500 NEA grant for the one-word poem “lighght,” enjoyed for years a strained relationship with his father, who called him “my pot-smoking son.” The elder Saroyan was particularly enraged with Aram for selling the author’s personal items—while he was still alive.

Daughter Lucy was another story. She tried her luck in Hollywood, appearing in films with Richard Pryor and her stepfather, Walter Matthau, then wound up as the companion of Marlon Brando. Her name is remembered in rare book circles because, like her brother, she has sold off personal items relating to her father. (Attempts to contact both children for this story were unsuccessful.)

As Saroyan lay bedridden with cancer in a Fresno hospital, the two children paid him final visits. He hadn’t seen either in years. In the spring of 1981, Aram chronicled the last few weeks of his father’s life as they occurred, and after Saroyan’s death that account was published as the book Last Rites, a memoir so nasty that one magazine ran an excerpt under the headline “Daddy Dearest.”

When the will was read, Aram and Lucy discovered they had been disinherited by their father.

After his death, the literary affairs and effects of William Saroyan were left in the hands of a private group, the William Saroyan Foundation, first created in 1966 and initially run by three trustees—William Saroyan, his sister Cosette, and his brother Henry. Begun for tax purposes, the foundation underwent restructuring over the years, according to former foundation attorney Robert Damir. Saroyan expanded the group to include more business-minded people on the board of trustees, and when it came time to draft a final will, the foundation provided a logical vehicle for planning an estate.

Although a 1966 document stated specifically, “It is the earnest, but non-mandatory, wish of the founders of this corporation that a majority of the trustees should at all times be members of the family of William Saroyan or his blood relatives or his descendants,” by the 1990s, no relatives remained on the board of the Saroyan Foundation.

The president of the organization is Robert Setrakian, a fellow Armenian whom Saroyan met at a funeral. Setrakian’s background was as an attorney, vintner, and businessman; he sat on many boards of directors, and held memberships in many exclusive private clubs. He was named executor of the estate, but had no previous experience in literary estates.

The Bancroft Library at U.C. Berkeley seemed a logical fit as a repository for Saroyan’s papers. Other prominent western American writers’ collections were on the Bancroft’s shelves, including Ambrose Bierce, Mark Twain, and Gertrude Stein, as were the papers of City Lights Books. The Berkeley campus also offered a department of Armenian studies, and Saroyan had mentioned the furtherance of Armenian culture in his will. James Hart, the charismatic and influential director of the U.C. Berkeley Bancroft Library, was a friend to William Saroyan, and would serve on the foundation board.

After Saroyan’s death, staffers of the Bancroft were dispatched on a mission to retrieve materials from the writer’s two tract homes in Fresno, which were completely filled with manuscripts, papers, books, and oddities such as the rubber bands and kleenex. According to a Bancroft internal memo, the project demanded six three-day trips. The staff poked and sorted through hundreds and hundreds of musty boxes, under court order to take only papers and writing-related items, and to ignore personal effects such as clothing. One garage took five days to examine, and the San Joaquin Valley heat was so stifling, at one point someone actually fainted into a pile of manuscripts.

The materials were delivered to the Bancroft in October 1982, and its staff spent the next two years in the basement manuscript and archival processing room arranging the collection. The results yielded 121 boxes of correspondence, 57 cartons of manuscripts, and daily journals chronicling the last 47 years of Saroyan’s life, all measuring over 180 linear feet of material. The completed Finding Aid—that is, the index listing the contents of the entire archive—ran nearly 300 pages. Saroyan’s was the largest collection in the library by far.

Other personal memorabilia collected from Saroyan’s homes in Paris and Malibu was stored on the fourth floor of the Fresno Metropolitan Museum. Among this group of materials was a panoply of other strange things the packrat Saroyan had refused to throw away: used typewriter ribbons, string, rubber bands, jars of rocks and shells, trunks of broken clocks, books and phone books filled with doodlings, boxes of junk mail and brochures, hairbrushes, and bags of his own fingernail clippings.

The bulk of the archive was noted in foundation tax returns as being worth approximately $1.6 million.

After a lengthy process, the estate of Saroyan was finally probated in December 1984, almost four years after his death. Things seemed to be moving slowly, but on track. Articles appeared in the press about the Saroyan papers, which developed a reputation as a very large and unusual collection. The Los Angeles Times Magazine ran several pages of photos from the Bancroft archives.

According to an internal foundation memo from the late 1980s, official approval had been received for issuance of a William Saroyan postage stamp, to be released in 1991, on the 10th anniversary of his death. The North Beach street Adler Alley, in front of the Specs’ bar on Columbus Street, was rechristened Saroyan Way. Several hundred permission grants were approved, and 53 hardcover publications were mentioned.

The Saroyan legacy was, however, hardly flooding bookstores. According to the memo, a mere five books had been published or republished since 1982, none by major houses. Longtime friends and relatives grew increasingly frustrated with the foundation, among them the foundation’s own attorney, Robert Damir, who, by 1988, had had enough.

Owing to lawyer/client privilege, Damir chooses his words carefully: “I just felt the foundation was not doing what I knew Bill Saroyan wanted to have done.”

Anthony Bliss, the rare book and manuscript curator at U.C. Berkeley's Bancroft Library, wrote the Saroyan Foundation in 1995, saying, “We feel that William Saroyan is a major American writer whose papers deserve professional preservation, cataloguing and handling. The Bancroft Library would make an ideal permanent home for his papers, and we hope that at some point the foundation will wish to place them here.”

The Bancroft had patiently curated the Saroyan papers, and was ready to take the next step. The foundation did not respond. The foundation had other plans.

Some of those plans were suggested in a memo dated Nov. 6, 1995, that Stanford Head Librarian Michael Keller sent Stanford President Gerhard Casper. In the memo, Keller referred to the university as an “institutional curator of culture” that “will produce some collection decisions which some will regard as controversial…I am mindful as well that some decisions we make together deemed controversial now will seem prescient, foresightful, prophetic later.”

He then promised Casper that the library would “stay alert for ‘targets of opportunity,’” adding that discussions had already begun “regarding the William Saroyan Archive.”

In fact, Keller and Saroyan Foundation President Robert Setrakian met and forged an agreement, signed on Nov. 22. It stated specifically that the foundation would move all of its Saroyan papers from Berkeley to Stanford. Stanford would accept the papers, on specific terms. The university would establish a William Saroyan Curatorship in American and British Literature. Stanford would establish and maintain an International William Saroyan Writer’s Prize. And if university officials agreed to do those things, the collection's transfer to Stanford would be permanent.

At a foundation meeting the following month, the trustees listened as Setrakian reported the proposed terms, which included the transfer of all commercial rights and copyrights related to the Saroyan collection. In other words, the foundation would transfer ownership of the $1.6 million collection to Stanford—and receive no money in return.

The board approved the agreement, and further requested that Stanford alumnus Setrakian be nominated as the university’s first honorary curator of the William Saroyan Archive.

The paper trail that would justify the transfer was begun months in advance. A petition was prepared to obtain Superior Court approval of the transfer to Stanford, “to the extent it might be considered inconsistent with the terms of the will of William Saroyan.” A judge signed the petition. The foundation also obtained a letter from Attorney General Dan Lungren, avowing that he had “no objection to the proposed agreement” between the foundation and Stanford.

Then, on April 4, 1996, Bancroft Library Director Charles Faulhaber opened a letter to him from the Saroyan Foundation, signed by Robert Setrakian. This was no routine missive; this was a bomb. The carefully crafted one-page letter opened up in complimentary and congratulatory terms, but in the middle, Setrakian suddenly and coldly requested the library’s cooperation in transferring all the Saroyan papers and materials to Stanford. Faulhaber would be contacted directly to “arrange for pick-up.” Attached was the signed Superior Court order approving the agreement between the foundation and Stanford.

To say the transfer shocked the Bancroft Library is to put things mildly. The Bancroft was known worldwide as the home of the Saroyan papers. Saroyan’s materials had been on deposit at U.C. Berkeley for as long as most could remember. Since the 1960s, the library had stored, cataloged, and provided reference and photocopy service for portions of the collection. The staff had devoted two entire years to processing it. Unlike Stanford, it was Berkeley that had an Armenian studies program and a William Saroyan chair, funded by the Saroyan Foundation. And the universities shared a joint library borrowing system.

Faulhaber wrote the foundation, expressing surprise and saying he was “perplexed” that Setrakian and company were not willing to discuss the transfer with Bancroft officials before acting. The following month, UC Berkeley attorney James Holst wrote the state Deputy Attorney General’s Office, addressing and disputing each item in the court petition approving the transfer. Holst asked the Attorney General’s Office to consider a rehearing on the transfer of the collection. Such a rehearing, he suggested, could enable the court to determine the matter with a full understanding of the facts.

The letter was written in polite legalese, but underneath were tough allegations. Holst was suggesting that foundation trustees may have deliberately withheld information from the court and the Attorney General’s Office, in order to downplay the Bancroft’s relationship with the Saroyan papers and hasten their transfer to Stanford. He also warned of a potential conflict of interest; the foundation’s president was to be working with Stanford as an honorary curator, possibly receiving compensation.

The war of words was on.

Seven days later, the same office received a rebuttal letter from Alan Nichols, attorney for the Saroyan Foundation, accusing Berkeley of stalling on delivery of the papers, and claiming U.C.. was making statements in the press that “attempted to embarrass the Foundation and its officers.” Nichols (also, coincidentally, the chairman of the Associates of the Stanford University Libraries) listed other instances when Berkeley supposedly had failed to treat the foundation properly. He warned that the attorney general should not be suckered into supporting Berkeley’s “ill-founded attack,” and concluded smugly: “There are enough problems in state law enforcement without initiating a new Big Game of Cal versus Stanford.”

The following week, Bancroft President Faulhaber fired back with a press release that said, “Cultural property is not a football.”

The Bancroft subsequently received a letter from the Attorney General’s Office, acknowledging that there had been “an arguable lack of consideration or courtesy” in regard to the transfer of the Saroyan collection, but stating the sudden action by Stanford “does not equal breach of trust or malfeasance.”

Berkeley’s attorney responded, disputing points made by the foundation attorney, but it was purely for the record. The collection now belonged to Stanford.

Leaving aside the questions of where the Saroyan papers should reside, and whether Stanford paid adequate compensation for them, one thing is very clear: The Saroyan Foundation did a terrible job of gathering and managing the collection.

In 1990, Bancroft Library Director James Hart passed away, and with him also disappeared any library influence on the Saroyan Foundation board. Bohemian Club librarian Andrew Jameson joined the board, presumably on recommendation from Robert Setrakian, who happened to be president of the Bohemian Club.

Also during 1990, William Saroyan’s sister Cosette died. His daughter Lucy moved into the family home on 15th Avenue in San Francisco, and for the next few years Saroyan items started popping up in stores and pawnshops. A national news story reported that William Saroyan’s 1943 Oscar statue was displayed in the cluttered window of a Mission District pawnshop, surrounded by used jewelry and cameras. Advertisements appeared in magazines, listing for sale various books and correspondence, including letters to Lucy.

Neighbors of the 15th Avenue house spoke of wild parties, and police were called more than once. After a Superior Court judge ruled the home, co-owned by the foundation and Cosette’s estate, could be sold to the beneficiaries of that estate, it was purchased by Saroyan’s niece, Jacqueline Kazarian, and her husband.

The new owners inspected the home and were disgusted: a leaking roof, ruined floors, weeds that had grown to 10 feet tall, evidence of drug use, and a door damaged when a boyfriend of Lucy’s had apparently tried to break into the residence. They obtained a court order and threw Lucy Saroyan out of her own father’s home.

In a sworn court declaration filed in 1996, Robert Setrakian admitted the Saroyan Foundation had insufficient resources to carry out the author's dying wishes, saying the organization “has no experience nor ability to raise the necessary capital to operate as a separate entity and still be consistent with the Will and intent of William Saroyan.”

The foundation’s last tax documents available to the public, for 1995, list royalties from sales of Saroyan’s books in over 40 countries to be just $34,938. Investments brought in another $37,000, but the foundation’s legal fees that year were $38,000, and Setrakian’s annual salary as board president was $20,000. The estate was not getting rich.

Despite the expressed wishes of his will, the foundation had never established an office at Saroyan’s home on 15th Avenue, nor at his homes in Fresno. Instead, the foundation sold the residences. Despite his will, the foundation never hired a curator to monitor his literary affairs. Even though his will left nothing to his children, they successfully sued the foundation and now own renewal rights to over 300 copyrights of his work. Despite the precepts expressed in the original articles of incorporation for the foundation, it had not kept family members on the board of trustees. Despite Saroyan’s dream that his work would be studied and enjoyed, the archive had remained completely inaccessible to the public.

According to Saroyan’s own words, the executor of his estate was not to “sell or assign any copyrights, published or unpublished manuscripts, copies of my works or any part of the property constituting The Saroyan Collection.” In fact, according to court documents, Setrakian and the foundation have now relinquished all ownership in all Saroyan works to Stanford University.

Since 1963, Berkeley book dealer Peter Howard has been one of the world’s premier dealers of modern first-edition and antiquarian books. He is a past president of the Antiquarian Booksellers of America. He doesn’t need to publish catalogs to promote his work. Like most in his field, customers know who he is.

Howard is quite familiar with the Saroyan Archive, and its value. He has been asked to appraise significant pieces of the collection twice—first the Bancroft collection, which took him more than five months, and then another 100 boxes of Saroyan paraphernalia discovered later at the 15th Avenue home.

Among the 400,000 volumes that inhabit Howard’s two-story store, Serendipity Books, on Berkeley’s University Avenue are some of the last items of Saroyan materials not yet in Stanford’s possession. The haphazard decor suggests either the store has just opened up, or is in the process of closing forever. There are no signs anywhere to aid navigation.

One large box marked “Selznick 4” teeters on a stack of others. Random titles radiate from shelves and stacks, representing the ultimate in obscure reading: Popular Religion in the Punjab Today, Collecting and Restoring Scientific Instruments, Love’s Cross Currents by Algernon Charles Swinburne, a shrink-wrapped bibliography of fiction written by L. Ron Hubbard, a bound screenplay by Paul Theroux.

And in the middle of it all, surrounded by stuffed kitty cat plush toys, who silently guard the domain, sits the gray-bearded proprietor at a large computer. Either you know what you’re looking for, or you don’t belong. All requests are funneled through one person—Peter Howard.

Serendipity has two bookshelves of Saroyan. A first edition of his very first book, The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, is priced at $375. The real goodies, though, are kept in a locked filing cabinet, from which Howard produces 43 Saroyan journals, dating back to 1934. The ruled notebooks chronicle the years before his Pulitzer, before his marriage and children, when he was a young man living in San Francisco, enjoying his first taste of success.

Some journal pages list hundreds of ideas for stories and novels, all neatly written in Saroyan’s hand, listing possible titles: “World of Trouble,” “Well Well Well,” “All Manner of Evil.” Others contain but one random personal note. “Something about watermelons in a story of summer: clarity of life” is scrawled across one page. Another reads, “Before the year ends I must write 6 or 7 novelettes: 15 to 20 thousand words each: each an experiment in both subject and treatment.”

“I bought a lot of stuff from Lucy,” Howard says, “and none of it had I ever seen before. None of it was in my appraisal. It was not in Saroyan’s estate when he died, to the best of my knowledge.”

He hands over a box that contains sequential drafts of the screenplay The Human Comedy, including notes and letters from fans of the movie. Some pages are half-filled with typing, others have but one sentence, false starts that were nevertheless saved. It is immediately apparent that Saroyan was a perfectionist who seemed on a mission to record every waking thought. For all his egomania, Saroyan remains one of the few authors whose obsessive self-chronicling allows readers and scholars to peek through a window into the creative process and observe the revisions and decisions from 60 years ago recorded forever. A word crossed out, a phrase added in pencil—one almost jumps into the mind of Saroyan, following along with his musings and word choices.

On top of the screenplay, a piece of note paper appraises the box contents at $16,237.50.

“The archive could be worth so much,” Howard remarks, watching me skim through the pages. “People could dip into it and option one play or movie, and bring in a million bucks for the collection.”

From now on, any such dipping will be done only by people who represent Stanford University.

On Aug. 7, 1996, vans from Stanford University pulled up to the Bancroft Library, loaded up every last box of Saroyan material, including the catalog that Bancroft staff had completed, and hauled them all away.

“It was the sourest day of my career as a librarian,” remembers Bancroft Curator Anthony Bliss.

Concurrently, all Saroyan memorabilia from Fresno, Malibu, and Paris was relocated to Stanford. Friends say Saroyan would have never approved the move.

“This man was not a blue blood,” says Robert Damir flatly. “He did not have any truck with snobbery or blue-blood life, the country club atmosphere. None of that appealed to him.”

Even New York book dealer Jennifer Larson, a one-time board member of the Saroyan Foundation during the early 1990s, couldn’t believe it. “I was stunned about the transfer,” she admits. “I don’t know what’s behind it. I thought it was very sudden.”

Despite the abrupt maneuver, which some would refer to as “literary poaching,” U.C. Berkeley went ahead with its international Saroyan conference on Nov. 15 of that year. Titled “Saroyan Plus Fifteen,” the conference featured prominent Saroyan scholars and writers, and the inauguration of the Bancroft Library’s Krouzian Study Center for Armenian students. The event was sponsored by Berkeley’s English department, its Armenian students and alumni, and the Saroyan Foundation.

Last May, Stanford retaliated, proudly hosting a weeklong “The Spirit of Saroyan” program on campus, a series of film screenings, readings, and talks culminating in a formal passing of the collection to the Stanford Library. In the commemorative keepsake booklet produced for the occasion, an introduction by Head Librarian Keller could scarcely contain the university’s excitement: “What a treasure trove this is!”

Keller went on to make two interesting announcements. The first William Saroyan Curatorship for American and British Literature, he revealed, would go to his colleague, the “incomparable William McPheron.” And the Honorary Curatorship of the William Saroyan Archive would be held by “the creative and thoughtful president of the Saroyan Foundation,” Robert Setrakian.

The Saroyan situation may never fully be resolved, or entirely controlled by Stanford. Nobody really knows how many letters, manuscripts, or xeroxes are still floating around. Saroyan events are still held at Berkeley. Fresno still hosts the annual William Saroyan Festival. And back in the Saroyan family home on 15th Avenue—the house William Saroyan built from an empty lot 60 years ago for his mother and sister—Saroyan niece Jacqueline Kazarian offers guided tours by appointment.

She has lived in the house with her husband since 1993, and spends much of her time and energy adding to this William Saroyan Cultural Resource Center. The building has received status as a city historical landmark, and even retains Saroyan’s original phone number. She feels uniquely qualified to represent her uncle. He was her first baby sitter. She cooked him dinners later in his life. And at his bedside in the Fresno hospital, she was the last to see him alive.

We meet in her living room full of delicate furniture. She sits me down, finishes reading a touching essay she has written about her uncle, then whips out a collapsible pointer. It’s time for the tour of the home. The upstairs is family heirlooms and furniture, but the basement is a Saroyan shrine, a work in progress that may never be completed.

His personal library remains intact, if dated: The Young Stalin, The Music Lover’s Handbook, Folk Tales of All Nations, Strange Animals I Have Known by Raymond Ditmars. Another wall is shelves of his books, several copies of each, with many first editions. Clippings and magazine articles are carefully presented on tables, many with little white signs indicating the year and other information.

The room smells musty. His walking sticks lean against the fireplace. A portrait of his father hangs above the mantel. On top of his player piano is a model for the stage set of the 1941 play “The Beautiful People.” A desk he made in high school nudges a wall.

His bedroom retains his original dresser, two small twin beds, and a framed original poster for the play “The Time of Your Life.” His black dress shoes are tucked under a stool. Kazarian confides that she recently attended a costume-required toastmaster’s event, dressed in his Army uniform. “And the shoes fit!”

The bathroom is arranged with his original bottles of cologne and aftershave, carefully laid out next to the sink. Another room contains his typewriter and Victrola. She says that when she and her husband moved back into the home, they discovered 10 boxes of rocks in the garage. In keeping with the spirit of her uncle, she decided to spread the rocks along the steps that border the side of the building.

“Would you like to hear his voice?” she asks. “You sit in the rocking chair.”

She puts on a tape recording of Saroyan as he listens to the radio, spinning the dial between stations, critiquing the programs, occasionally chuckling at the comedy. Essentially it’s a random scan of the dial in five- to 10-second chunks of audio, an aural diary of his peculiar listening habits.

“He did this every day,” she says. “These are unedited.” Some news snippets follow. Nothing remarkable happens.

She digs up another tape of him reading a short story from 1970.

“The speaker is William Saroyan,” he begins in his booming voice. “The writer of a short story called ‘The 50-Yard Dash.’ Which I now propose to read, holding before me a paperback book entitled My Name Is Aram. I am making this recording for Mrs. Milton Rubin.”

His introduction goes on in a loud, declarative, simple voice, as if small children are gathered at his feet. The story finally begins, a tale first published in 1940, about a 12-year-old paperboy named Aram who answers a magazine ad for a mail-order bodybuilding course. The narrator prepares for a track meet—envisioning himself answering the ad and soon transforming into “a giant of tremendous strength”—and describes the Charles Atlas-like pitchman, Lionel Strongforth:

“He was layered all over with muscle, and appeared to be somebody who could lift a 1924 roadster and tip it over. It was an honor to have him for a friend. The only trouble was, I didn’t have the money. I forget how much the exact figure was at the beginning of our acquaintanceship, but I haven’t forgotten that it was an amount completely out of the question.”

Jacqueline Kazarian chuckles at the tape, and looks out the window, over the treetops of Golden Gate Park to the Pacific, the identical view shared by her uncle as he wrote this story 60 years ago. She is no longer here. She’s in a safer place, a place where Saroyan belongs. Not packed away in acid-free boxes as victory trophies for competing universities, but alive in the hearts and minds of Americans, who appreciate the simple Saroyan-esque pleasures in life. The squeal of a happy child. The crisp bite of an apple. The warmth of red wine. The roar of laughter over a good story, told among friends.

Great piece! I wonder what's happened to the SF house since, do you know?