Requiem for a Church Supreme

After three decades of feeding the homeless, the only church devoted to John Coltrane now finds itself without a home

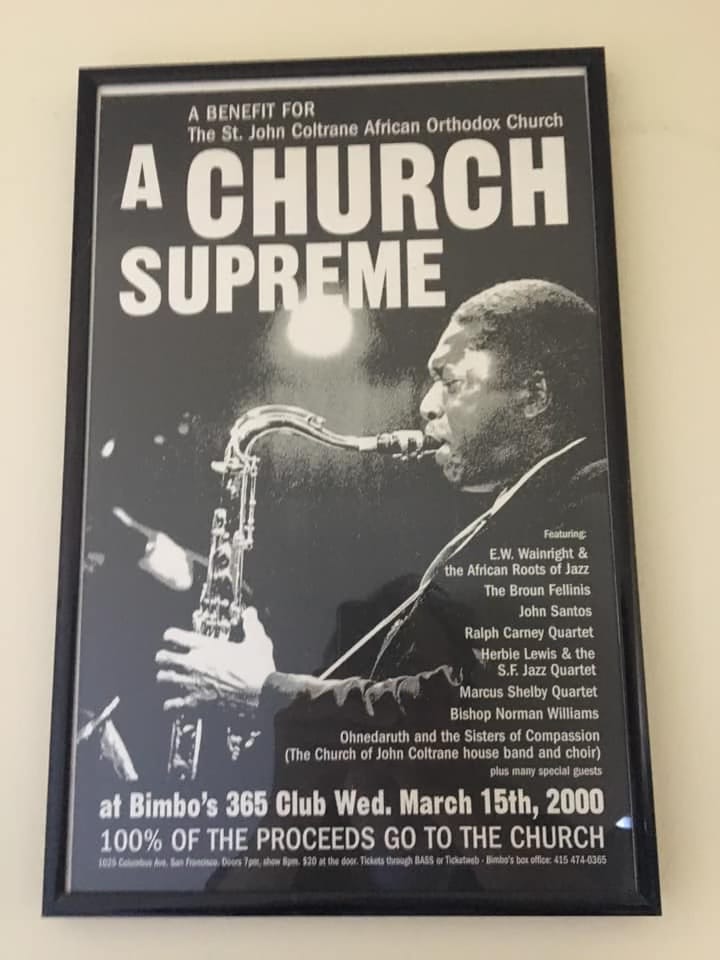

In the 1980s and 90s, I lived in the Western Addition of San Francisco, which had a large African American population at the time. A short walk from my apartment was the weekly jazz jam at the Coltrane Church. (As well as a pretty sketchy chicken joint called Dew City, with bulletproof glass, if anyone remembers.) The church was an unusual organization, listed in tourist guidebooks as an “only in SF” attraction. Young students in journalism schools always wrote it up for the campus publications. It was a secret thing. And it was amazing. At some point I learned the church was going to be evicted, and I wrote up this cover story for SF Weekly in January 2000. I was so taken with what they were doing, I decided to stage a benefit for them. So event producers Christie Ward, Michelle Barnett, and myself put on a gigantic Coltrane show at Bimbo’s in North Beach. Over 800 attended, with people sitting on the floor, and that poster is included at the bottom. Not listed was the emcee, my comedian pal Ngaio Bealum, who grew up in the Western Addition. I didn’t know that he was going to make weed jokes for three hours, but hey, it was a jazz show. Also, our stage manager was a roadie for AC/DC. It was a helluva night. And Jeff Ray, if you’re reading, let’s hear the tapes you recorded! The Coltrane Church has moved around a bit and is currently holding weekly services at the Magic Theater, at Fort Mason in the Marina District. In 2019 they celebrated their 50th anniversary. This article has been sourced many times, and it’s been offline for awhile, so here it is again, enjoy.

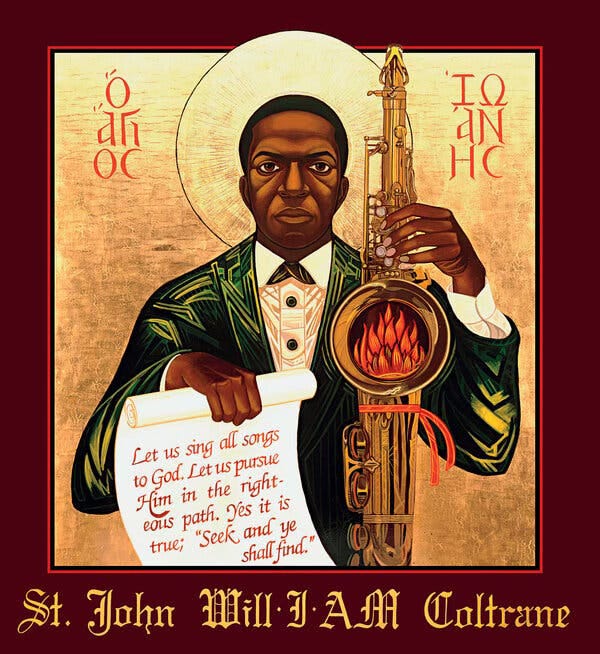

Artwork by Reverend Mark Dukes

Bishop King, 1981

“Do I care? Yes, I do. I wish I could have it like it was many years ago. But I know that the world moves on. And unless you move on with the world, you are in for a rude awakening.”

—San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, from a KQED documentary about the Fillmore and Western Addition

Sixty people—primarily white twentysomethings with goatees and dreadlocks—crowd into a small Western Addition storefront. Musicians carrying saxophone cases and drumsticks slip through the crowd up to the front. It’s immediately apparent that this is not your ordinary Sunday church service. The walls feature a series of ten-foot-high murals depicting saxophonist John Coltrane, and lyrics from his album A Love Supreme. The altar displays a portrait of a Black Jesus Christ.

A beatific African-American woman greets the room.

“Anyone here love John Coltrane?” she asks. People answer yes. Some raise their hands. Sister Deborah introduces herself, welcomes everyone, and explains that it is acceptable to do whatever the spirit moves you to do during the service. If you want to sit, fine. If you feel like standing and dancing, that’s cool. If you want to sing along, or grab a tambourine, even better.

“This is God’s house,” she explains. “We’re God’s children. So we wanna have a good time!”

She smiles wide, and asks how many in the room are locals. Three hands rise. The vast majority of this morning’s congregation is from somewhere outside the city—Texas, Arizona, Spain, New Zealand, France, Denmark, Sweden, and Ireland all are represented today.

Bishop Franzo King enters from behind a curtain, wearing bright purple vestments and sporting a saxophone around his neck. He kneels in front of the altar, crosses his chest, and turns to face the room. At this point in a service at this particular church, many things may happen. Bishop King may decide to read from the Bible. He may start a free-association sermon about John Coltrane, explaining that he was a “musical scientist,” and dropping in quotes from Malcolm X and Cornel West. Or the bishop might not say anything at all. He might stick his sax in his mouth, and the band might kick into a Coltrane composition that goes on for 30 minutes, with the choir singing along, and every musician getting time to play solo. The entire crowd might be on its feet dancing, clapping along, rapping knuckles against the walls. The pianist might move to a Hammond B-3 organ in the back of the room, and rip into a groove so furious that Bishop King will run over to him with a wireless microphone, stick the device directly into the organ’s speaker, and send out an ear-splitting cacophony of jazz that echoes off the walls and ceilings. And at that point, the bishop might scream, “YEAH! YEAH!”

Since 1971, the St. John Will-I-Am Coltrane African Orthodox Church has operated out of this Divisadero Street location, holding weekly services, feeding, clothing, and counseling the homeless, and teaching music and computer classes. After nearly three decades, a word-of-mouth reputation has earned the church mentions in travel guidebooks, jazz Web sites, and Coltrane biographies. Each Sunday, the room is filled to capacity.

But a peek inside the photocopied program for this service says something else is going on behind the scenes. A note from Bishop King, the founder of the church, warns of a “great transition,” and asks his congregation for financial support. In an increasingly familiar San Francisco scenario, another business is about to be evicted, because the building in which it had been leasing space has been sold. The business’ new landlord has doubled the rent, making it impossible for the business to continue. This time, though, the “business” is a church.

San Francisco is adept at fostering the creation of one-of-a-kind cultural landmarks, but not very good at hanging onto them. From topless dancing at the Condor to the Winterland hippie concert venue to the drag-queen emporium of Finocchio’s, civic institutions that once made headlines, in San Francisco and around the world, have faded into mere footnotes. The reason for this turnover is partly financial; as rents soar with the Bay Area’s flush economy, and trends change, some enterprises simply become unprofitable. Also contributing to this changing of the cultural guard, though, are the thousands of new residents the boom economy has attracted to San Francisco—residents who often have little or no interest in maintaining the city’s iconoclastic history. The Coltrane church seems to be a victim of both financial pressure and local neglect.

Bishop King and his flock have been told to leave their building by the middle of March. They have yet to find another location, even a temporary one, with a lease they can afford. King has consulted with an attorney, and even asked City Hall for support, but nothing has come of his appeals. In a few weeks, the church that feeds the homeless of the Western Addition will itself be homeless.

One could argue that the Bay Area embraces the spirit of the individual. It certainly boasts a large appreciation for jazz, which has been described as the music of both individualism and community. And the area provides freedom to worship almost any imaginable form of religion. But at this point, there doesn’t seem to be anything anyone in San Francisco can do to extend the future of a little church devoted to praising God through a patron saint of jazz.

A junked car sits on a trailer, sulking in the afternoon sun. Several homes sit abandoned in various states of decay. Farther up the same street is a line of industrial warehouses. This is Bayview-Hunters Point. After the Redevelopment Agency swept through the Western Addition in the 1960s, leveling entire blocks of Victorian buildings in a drive to “improve” the neighborhood through urban renewal, the Bayview was the one district where a displaced black population could, and can, afford housing.

Bishop King pulls up to his house in an old black Mercedes with a missing hood ornament. He steps out of the car, looks back as if it were an old friend who hadn’t repaid a loan, and shakes his head. Once inside his two-story home he removes his shoes, asking guests to do the same, and changes into black slacks and a dark blue turtleneck. After making a cup of tea, he selects some music from an enormous collection of Coltrane CDs and sits back in a chair.

He’s hesitant about discussing his church’s eviction, because he hasn’t asked for any press on the subject. This article wasn’t his idea. Although praised by umpteen national and international journalists—from Life, Vibe, the Wall Street Journal, the Bravo network, London’s Guardian, and many other media outlets—the church has been portrayed as quirky and silly by San Francisco’s mainstream media. So the bishop hasn’t bothered to make any noise. He just figures that God will allow something positive to happen.

What he can’t reconcile is the obvious importance of the church to the city, and the little regard the city seems to have for it.

“You know how they say that jazz is the ambassador for the United States? This church has been an ambassador for San Francisco, for the United States. We go to France three times and represent the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, and they say, ‘From San Francisco!’”

Coltrane’s music hums along in the background. A fiery minister who gives his all during sermons, King seems to be fighting an impulse to raise his voice.

“So we’re doing some work in terms of this city. We’re saying that the city has a certain responsibility to keep an entity as this not only alive, but properly edified. And that it should be in a position, in a house, in a place that represents not only the dignity of the city, but the dignity of the saint that we represent. And that if in fact that San Francisco leans so heavily on tourism, and you’ve got a little institution, a little spiritual community here, that’s bringing people from all over the world, without any hotel tax money ....” His sentence trails off, but as if playing a saxophone solo, he quickly regains momentum with another thought.

“People are coming from all over the world. The French Consulate—there was a man from Chile there last night. Said that Coltrane changed his life. He had heard about the church, and knew he had to come to this place.”

The Coltrane church does not advertise itself, nor has it ever made any attempt to build up its congregation. Until recently, it never bothered to pass the collection plate. It has survived in near obscurity, supported by private donations, bake sales, and commissions from T-shirts and postcards. Despite this deliberately downplayed public image, the organization has become extremely well known to a worldwide network of jazz fans.

But why in this city? King sips his tea and thinks about that.

“To me, to be significant to San Francisco is to be significant to the world. In other words, if I correct my behavior, it doesn’t just affect me and my family, it affects the whole community. As Coltrane says, the whole of the globe is community for us.”

Bishop King at the Sunday service, 2009, photo by Susie Biehler

The phone rings frequently. Each time King answers with the words “One Mind.” One of the church’s philosophical tenets posits that emotionally, we are all of one mind—one anger, one joy, one love. (An earlier version of the church was named the One Mind Temple Evolutionary Transitional Church of Christ.) The bishop advises one caller, a person in need of a bit of counseling, to hang in there, and he will call him back later. And then Bishop King begins to tell the story of how a church dedicated to John Coltrane came to be.

King’s parents and grandparents were Pentecostal ministers; music, he says, was extremely important to the service. And even though he grew up in Southern California, a major hub of pop and rock radio in the 1950s, King was allowed to listen only to church music (and, for some reason, country and western). In fact, his earliest memory of jazz comes from a church jam session by a Sacramento group called the Ford Brothers.

As a teenager, King was introduced to jazz in bits and pieces. One day he came home from high school and his older brother was playing “My Favorite Things,” a 1961 jazz version of the popular Broadway show tune sung by Mary Martin. This version of the piece sounded very strange, almost Indian or Middle Eastern.

“It’s John Coltrane,” his brother explained. “Jazz. Soprano saxophone.”

The two talked a lot about music. His brother kept coming back to the same idea: The kind of music you listen to is the kind of person you are.

“If you listen to jazz, then you’re progressive,” King explains. “If you listen to Top 10, Top 40, then you’re just with the crowd. If you listen to progressive jazz, then your mind is way ahead of everybody else’s. So we thought we was really halfway sharp. We were still comin’ out of James Brown, stuff like that, you know.”

Another heavy influence on his musical education came via an aunt from Chicago, who determined that her little nephew Franzo should become a hairstylist. King soon found himself on a Greyhound bus to Chicago, to check out a cosmetology school. An older cousin named Richard Dixon met him there, and introduced him to his music. Dixon owned a big collection of jazz records. Musicians King had never heard of. He thumbed through the albums. Sonny Stitt? Charlie Parker? Jazz Crusaders? King got to meet many of the top acts in person, because his cousin dragged him into the jazz clubs of the North Side.

“He was the kind of guy that was very open with the musicians. Run up to ’em, ‘Man, y’all soundin’ good, man! Hey, this is my little ole cousin from California.’ He just had that kind of rapport.”

After returning to L.A., King drifted north to San Francisco and met up with his older brother and a few friends; the group began holding what they called “listening sessions.” Whenever somebody had money for records, the young men would meet at someone’s apartment and listen to the music, trying to guess which musicians were playing on which albums.

King says he started calling it the Jazz Club, but it wasn’t just about listening to records.

“We could feel early on that the music was escaping the community that was producing it. And so we had a concern about that: How can we get the youth from the African community to get into this music for the purpose of benefiting from the properties that the music offers?”

It was fine if kids just wanted to listen to songs about love, or songs that made them dance, but King and his club had higher concerns.

“What was really disturbing me was that viewing the music through experience, and seeing how it really could deal with your thought patterns, and your aspirations, and your ideals and things—how do we get them to benefit from this?”

The answer was simple: force the jazz upon the kids. King found a regular house party in the Bayview district, where somebody had turned a garage into an ongoing hangout. People paid 50 cents at the door, and drank cheap liquor, and listened to rock ’n’ roll and rhythm and blues. At 2 a.m., the club was turned over to Franzo King, who had invited jazz musicians.

“We’d just set up. Guys like Norman Williams, and Billy Higgins, and Benny Harris, the guy who wrote ‘Ornithology’ with Charlie Parker. We did a thing called ‘I’m Black and I’m Proud Harlem Tea Party.’ We had fliers, and we put ’em out all over the clubs. The youngsters got hip to us after a while. They’d say, ‘Hey man, these guys are gonna cut off at 2 o’clock and start playin’ this jazz.’ And then we just killed that [early] part of it, and we started opening from 2 to 6 in the morning, and called it the Yardbird Club."

In 1965, Franzo King took his wife Marina out to celebrate her birthday, and also the birthday of his late father. At that time, as the city was bridging the gap from beatniks to hippies, rock ’n’ roll was not big yet, and jazz was still the primary genre for live music. Bay Area audiences lined up to see Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers, Lenny Bruce, Horace Silver, Dick Gregory, Tom Lehrer, Dizzy Gillespie, and Count Basie. Local musicians were also rising to national prominence, among them Cal Tjader, Dave Brubeck, John Handy, and Vince Guaraldi.

In North Beach there were strip clubs, of course, but also major jazz venues, including the Jazz Workshop and Basin Street West (now, respectively, the Hi-Ball Lounge and the Crowbar). The Western Addition still boasted a fair number of nightclubs, including the legendary Jimbo’s Bop City at Post and Buchanan, and, on Divisadero Street, the Half Note (now the Justice League) and the Both/And club.

Splitting the difference between these two neighborhoods was the Blackhawk at the corner of Turk and Hyde, where Miles Davis recorded his live albums. If jazz fans stayed home on Monday evenings, they tuned their televisions to Channel 9 and caught their favorite musicians performing on the nationally syndicated Jazz Casual program, taped at the KQED studios and hosted by San Francisco Chronicle jazz critic Ralph Gleason.

The Kings opted for the Jazz Workshop. Playing that night was the John Coltrane Quartet, at the height of its popularity. After squeezing into the narrow, smoke-filled room, King says, he heard something that was far beyond just another combo playing in another club. He has since referred to that evening as a “baptism in sound.” The performance would alter his life forever.

John Coltrane with the classic quartet, photographer unknown

The closest experience he could compare it to, he says, would be moments in church, during his Pentecostal youth, when the music and preaching would escalate and build to such a level that the congregation felt a direct and intimate communication to God. The old folks called it “the Holy Ghost falling on the people.”

“It manifested in different people in different forms,” recalls King. “Some people would dance, some people would cry, some people would rejoice, some people would speak in other tongues. But for that moment, that period, time was arrested, so to speak. You were at the obey of the Holy Spirit.”

He had that same feeling that night at the Jazz Workshop. When the quartet took a break, bassist Jimmy Garrison stayed onstage and played a solo with such commitment that an unnoticed string of drool hung out of his mouth, dangling almost to the floor.

“I realized that the music of John Coltrane was representative beyond culture,” King says. “And it wasn’t just a cultural or ethnic thing. It was something that was higher.”

He leans forward. This is an important point. This is the genesis of his church, the core of his belief system.

“In other words, you begin to see God in the sound. It’s a point of revelation,” he says. “It’s not something that happens with absolute clarity, but it begins an evolution, or a transition, or process. The consciousness level, that opening, is evolving. Baptism is what it is.”

Although he lived and recorded on the East Coast, John Coltrane visited San Francisco frequently. According to the 1999 Lewis Porter biography John Coltrane: His Life and Music, Coltrane first performed here in 1950 with Dizzy Gillespie’s band, at Jimbo’s Bop City. He would return to play every major venue in the Bay Area, including the Civic and Masonic auditoriums, as well as the Monterey Jazz Festival.

In his formative years, the shy young saxophonist from Philadelphia apprenticed under some of the best bandleaders at the time—Earl Bostic, Johnny Hodges, Gillespie, Davis, Thelonious Monk. As Porter points out, Coltrane wasn’t born a boy genius like Charlie Parker. He had to work at his talent. Friends would find him backstage in the dressing room between sets, practicing constantly for the perfect series of notes. While on tour, if hotel guests complained, he laid on the bed and silently fingered the keys. At night he fell asleep with the horn still in his mouth.

Coltrane was known as quiet and polite, wasting few words in conversation, but as with many jazz musicians, the hectic life of touring led him to booze and heroin. After watching him nod off onstage one too many times, Miles Davis fired him from his band, then the hottest quintet in the industry. Coltrane could easily have given up, but what he did next, in 1957, illustrates his essence. He went home to his mother’s house, drank glasses of water, and went through cold turkey by himself.

Newly clean, he took Monk up on an invitation to play a series of gigs, and then rejoined Davis for more recordings, which produced the classic album Kind of Blue. His style was starting to change. He seemed to be on a mission now. His solos were often hailstorms of scales and arpeggios—an aggressive, intense style one critic dubbed “sheets of sound.”

Coltrane assembled a group of musicians to back him, and recorded several albums on the Prestige label, before jumping to Atlantic Records. His 1960 release Giant Steps marked a milestone of sorts, the first record for which he wrote all the compositions. It was also notable for its fast, complex, impossible-sounding solo lines. The album is now required study in jazz education classes.

John Coltrane in the studio

Immediately after that Coltrane put together what he considered his dream quartet—a young virtuoso named McCoy Tyner on piano, the powerhouse drummer Elvin Jones, and, for the majority of the time, Jimmy Garrison on bass. This group would play together for the next several years, recording for the new Impulse! label, and redefining the conventions of jazz.

The quartet’s 13-minute version of “My Favorite Things” proved so popular that many thought Coltrane, rather than Rodgers & Hammerstein, had actually written the song. But successive albums baffled both listeners and critics. Africa/Brass utilized an orchestra and unfamiliar rhythms that Coltrane had borrowed from African folk recordings. At other times, his playing was so loud and full of skronks and shrieks and attempts to hit three notes at once that critics referred to his music as “anti-jazz.” Down Beat magazine started assigning two writers to review Coltrane, because one would invariably trash him. Rather than argue, Coltrane answered criticism by recording albums of ballads and standards, including two with crooner Johnny Hartman and pianist Duke Ellington.

Coltrane’s true calling was the so-called modal structure, which doesn’t follow a typical blues chord progression, but lets the music weave in and out of a single scale. With everyone playing essentially in one key, soloists have a chance for endless improvisation. One example would be “Lonnie’s Lament,” from the 1964 Crescent album; for most of the 11-minute track, Jones and Garrison anchor a syncopated groove, and Tyner and Coltrane head off in all directions, the result so complex and beautiful that it’s easy to forget the music is wrapped around a single scale.

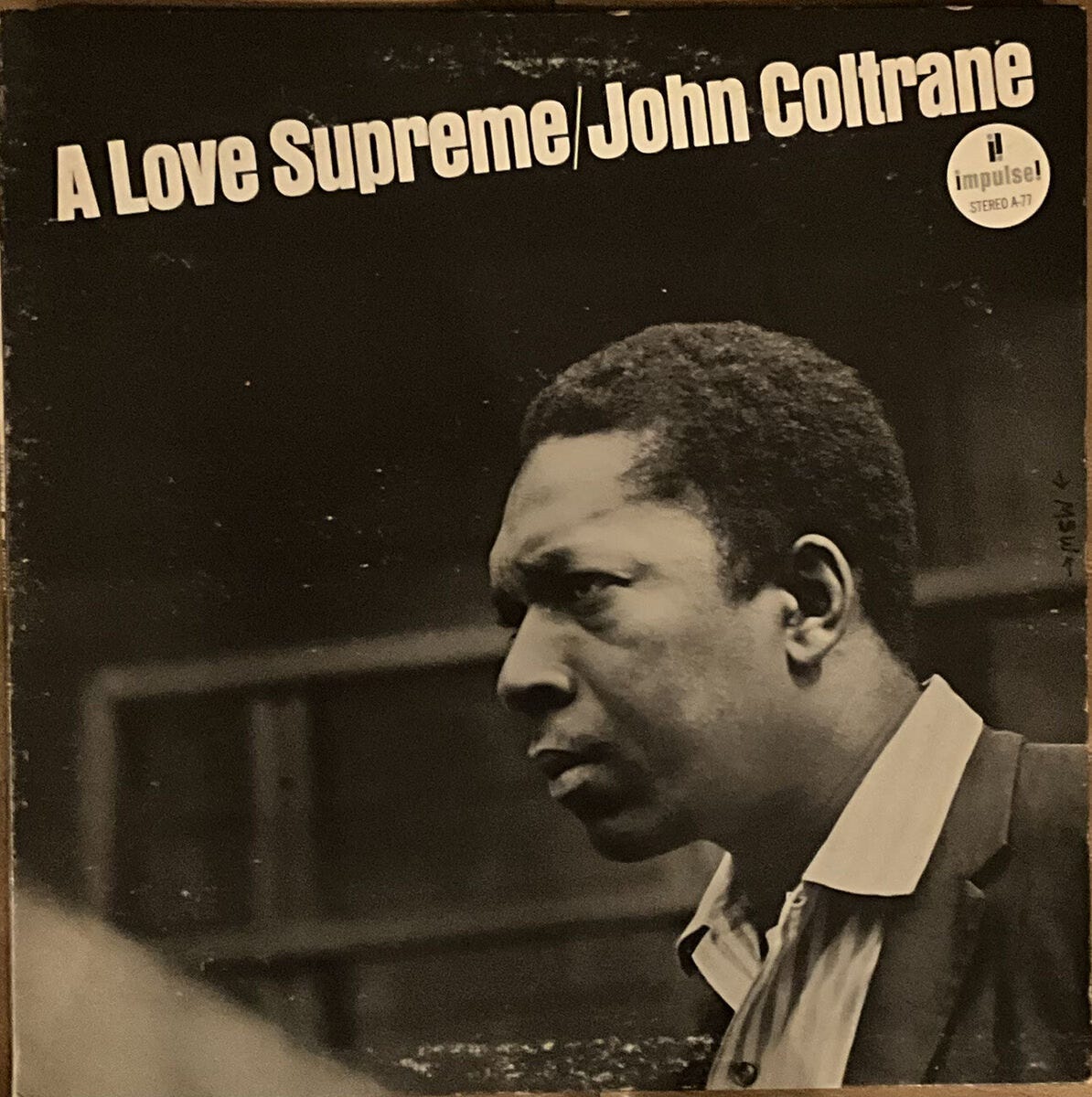

That same year, the quartet set aside a day and recorded A Love Supreme, the first jazz record to sell 500,000 copies. Much like a symphony, Coltrane structured the record in four movements: “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” And it was essentially all improvised. None of the quartet learned the music until the day of the recording.

Listeners opened the album and saw immediately that something was missing in the accompanying essay. There was none of the usual pretentious blithering on; for the first time, Coltrane had written the liner notes himself.

“During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music. I feel this has been granted through His grace. ALL PRAISE TO GOD.”

A Love Supreme, vinyl, 1965

People understood that this “awakening” probably coincided with Coltrane kicking his heroin habit, but the rest of the notes were equally spiritual. The accompanying poem “A Love Supreme,” also written by Coltrane, began: “I will do all I can to be worthy of Thee O Lord. It all has to do with it. Thank you God. Peace.” (Porter, the Coltrane biographer, maintains that the album’s final movement, “Psalm,” is actually a musical interpretation of these words.)

If one could point to a single record that best sums up the Coltrane quartet, this is it.

The group would play together for another year or so, before its members trickled away and were replaced. Coltrane pushed his experimentation still further. Audiences expecting to hear “My Favorite Things” in concert watched him play an avant-garde solo that lasted over an hour, and ended up walking out. The posthumous album Om was supposedly recorded under the influence of LSD. But he released records steadily up until his death of liver cancer in 1967. The final albums are difficult listening for even the most dedicated Coltrane fan, but they demonstrate that he was obviously still pushing himself for what was just out of grasp, attempting to translate sounds he was hearing in his head into music out of his horn.

The memory of John Coltrane is still present in the jazz world. Record companies have rereleased all of his albums, including several box set collections, and bootlegs continue to circulate. He is the subject of a dozen biographies. Relatives have opened up the family home in Philadelphia as a John Coltrane Cultural Society. A memorial Coltrane concert is held each year in Boston. Rock musicians who acknowledge his influence include U2’s Bono, Carlos Santana, and the late Jerry Garcia. Surviving members of the original quartet Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner still play the occasional Coltrane composition in their live shows. Saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, a mere toddler when his famous father passed away, is a well-respected musician in his own right.

San Francisco sax player David Boyce, of the Broun Fellinis jazz trio, still listens to A Love Supreme every Dec. 9, the day it was recorded.

“I have to treat that stuff with kid gloves,” Boyce says. “There’s so much of it. Trane is just heavy. He did nothing light. Nobody went for it like that. He could play 9 million things on an F-minor chord. Bird had an effect on people, but Trane is probably the only one you could start a church from.”

John Coltrane returned to San Francisco in 1966, and Franzo King again brought his wife to the Jazz Workshop, but Marina was refused admission because she didn’t have identification. The following year they looked forward to Coltrane appearing again at the Workshop, but he canceled the gig, and died a few months later. King admits that his life had changed by that time. He was still trying to run jazz clubs and parties, but saw very clearly that he couldn’t get Coltrane out of his head. A quote from the sax player kept coming back to him: “Yes, I think the music is rising. In my estimation, it’s rising into something else, and so will have to find this kind of place to be played in.”

“I think that was the key thing for me,” King says. “‘Ah, church. That’s where we have to do it. To the church.’ That’s where it changed.”

When A Love Supreme was released two years earlier, King didn’t even bother giving it a listen. All the stuff about God—it looked like Coltrane had been snatched up by the Jesus freaks. But that was then. Now, King set about converting a downstairs apartment of his house into a chapel. People came over every Tuesday at midnight, listened to the Love Supreme album, and prayed and fasted for 24 hours. King didn’t have a great desire to be the leader; he just wanted to supply people with information. But as the circle evolved, he eventually ended up leading the service. The group called itself the Yardbird Temple.

As the idea grew, King realized they needed a larger space. He moved the group into a storefront space on Divisadero, just across the street from the Both/And jazz club. The church was told that the address was once the home of the Theater of Madmen Only, a community that was one of the first to experiment with LSD in San Francisco. Rent was $225 a month.

It soon became clear, King says, that they owed a responsibility to the community. Up to this point, they had been just fasting for a day, and then feeding everyone to break the fast. One of the church’s main criticisms of traditional faith organizations was that they had failed to alleviate the suffering of the people, and ignored those on the streets. The Coltrane-themed church hoped to make a concrete contribution.

“With Anchor Rescue Mission, you’d have to come in, you’d have to listen to a sermon, you’d have to sing ‘Rock of Ages,’ and all this other stuff, to get a baloney sandwich,” says King. “And we were saying, ’We’re not gonna come like that. What we’re gonna do is invite the people to sit down, give them a copy of John Coltrane’s testimony A Love Supreme, and play the music.’ And that’s what we would do. Coltrane said, ‘Let the music speak for itself.’ So that was our preaching. We’ll just put the music on, and baptize the people in sound, and let it go from there.”

The church originally used the jazz band that had played at the old Yardbird Club, but although the musicians could play Coltrane’s music, the service as a whole didn’t exactly work out. “Some of the cats couldn’t understand what was going on, you know. Because we’d go from “Giant Steps” to [sings] ‘Jesus is on the main line, tell him what you want!’ They’d go, ‘What?’ It was just kind of hard for them, in that they had not been born again.”

Eventually the music problems were ironed out. A church member started a weekly Coltrane-themed radio program on the KPOO station, also located on Divisadero. Marina King organized the church’s Sisters of Compassion, which acted as a choir for church services and solicited church donations at the SFO airport. The airport began donating clothing and luggage to the church from unclaimed lost and found items. The new Coltrane Memorial Outreach Programs offered free meals twice a week, counseling for the troubled, clothing and shelter for the needy, and calligraphy classes.

Around 1972, King recalls, members of the church went to Berkeley to see a performance by John Coltrane’s widow, pianist Alice Coltrane. “We spent almost two years with her in study and meditation. We benefited greatly from her. She opened our eyes to so many different things spiritually, and about John’s life personally,” he says. “She elevated our community in such a way. Very anointed woman, very wise.”

During this period, however, many fringe religious organizations rose to prominence in the Bay Area, from Jim Jones’ People’s Temple to the Moonies, the Hare Krishnas, and Synanon. King remembers the era well, including the stigma his church picked up. “‘Oh, they’re the Coltrane cult down there.’ I think people still feel that,” he says. “I think there’s still people who are concerned whether we’re down here worshipping John Coltrane, and it bothers them that we might be.”

Cult hysteria increased with the Jonestown mass suicide in Guyana. And in 1981, Alice Coltrane turned around and sued the One Mind Temple Evolutionary Transitional Church of Christ for $7.5 million, claiming the group was exploiting her husband’s name and infringing on copyright laws.

The news hit the inside front page of the Chronicle: “Widow of ‘God’ Sues Church.” A photo showed King, identified as Ramakrishna King Haqq, sporting a big Afro and beard, sitting in front of a Coltrane-decorated altar. The article outlined the dispute: Coltrane was asking the church to stop desecrating her husband’s image; King was saying he didn’t care what the allegations were, because the music was healing, and allowed people to lead richer and more productive lives. He told the reporter that the church had even started a movement to get “A Love Supreme” named as the national anthem.

Representatives from the African Orthodox Church in Chicago heard of the lawsuit, and sent a vicar to meet with King. This offshoot of Catholicism, founded in 1920 by a United Negro Improvement Association leader named George Alexander McGuire, was a popular affiliation for storefront churches in the eastern United States. The representatives told King they were looking to establish another church in the west.

King was reluctant to get involved. The lawsuit with Alice Coltrane had gone nowhere, but he felt gun-shy. Why should he get caught up with another faith? To him, John Coltrane’s picture would always be the highest in his church. But after he met with Archbishop George Duncan Hinkson, the distinguished and charismatic leader of the African Orthodox group, he relaxed. Hinkson assured him he could keep the Coltrane connection.

Bishop King and Mother Marina traveled to Chicago and studied for two years with the principal members of the African Orthodox Church. After King received his Doctor of Divinity degree in 1984, the couple returned to San Francisco. King’s church was no longer a group of revolutionaries who aligned themselves with the Black Panthers. Now they were part of an established faith. To King, the African Orthodox affiliation felt like a Good Housekeeping seal of approval.

“Up to this point, we’re doing Sanskrit chanting, things we got from the Holy Ghost, things I brought from the Pentecostal movement, somebody else brought from their Catholic expression, somebody was a Buddhist,” King says. “We had all this hodgepodge of things, but when we became under the umbrella of the African Orthodox Church, we had to accept the Sacraments. We had to really deal with being Catholic. So how do we do this? To keep John here?”

The church simply took Catholic prayers and married them to Coltrane compositions. “The Lord’s Prayer” was chanted to Coltrane’s “Spiritual.” “The Lord Is My Shepherd” was sung to the sax line from “Acknowledgement.”

“The music and the liturgy is incorporated,” says King. “It’s no more than what some of the European classical composers did for the church. Basically, that’s what we did. The archbishop said, ‘There’s hundreds of liturgies. You have a Coltrane liturgy.’”

There was one catch in becoming African Orthodox. King and his church couldn’t treat Coltrane like God, because, for African Orthodoxy, there is only one God. So King made Coltrane a saint.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, the church received regular press attention. Travel guidebooks listed it as one of the hidden treasures of San Francisco. Neighbors up and down Divisadero Street got to know church members, and how pleasant they were. Street people knew to drop by Sunday and Wednesday afternoons for a free hot meal. Bishop King performed weddings and funerals. Volunteers launched the www.saintjohncoltrane.org Web site. And core church members still listened to A Love Supreme at least three times every day.

The church band became a tight unit. Franzo and Marina’s children had been taken to jazz clubs at a young age, and grew up surrounded by music. Franzo Jr. developed into a first-rate saxophonist. John Coltrane King slid behind the drum kit. Wanika King picked up the bass guitar (and also took on hosting duties of the weekly KPOO radio show). Franzo Jr.’s high school friend Fred Harris manned the church piano. And holding down the tradition of Coltrane’s musical style was a saxophonist and church elder named Father James Roberto Haven. This core group now provides music for the Sunday services, featuring a regular repertoire of Coltrane compositions that mutate into long jams, allowing plenty of room for other guest musicians. Occasionally the band plays in clubs, and the French government has invited the group to perform in jazz festivals.

When David Boyce moved to the city in 1991, before forming the Broun Fellinis, he spent many memorable Sundays playing his horn at the church. “They were steppin’ out,” he says. “There must have been six saxes up there. Being in church, playing space music—it was great. If they happen to believe that one of the most intense musicians of the 20th century is a saint ....” He shrugs, as if to say, So be it.

Now Bishop King is pacing back and forth across the carpet. This part of the story is getting him agitated.

David Bell had been the church’s landlord for some 20 years, but he passed away in 1998, leaving an unfinished negotiation on a new lease. Nothing had been finalized, but this was no big deal. In 27 years of paying rent at 351 Divisadero, the church had been through several landlords and lease agreements. It had always worked out. But that was before.

In May, a San Francisco property owner named Naseef Musleh purchased the building that houses the St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church. The church proposed a new lease, King says, but Musleh rejected it. Then, King says, Musleh raised the rent from $1,100 to $2,250 per month; suggested that the church close down its food program because it did not have the necessary kind of kitchen; said the church needed to take out $1 million in insurance; and told King the church would not have a lease, but would rent on a month-to-month basis.

King says he went to a lawyer, but received only bad news. “He tells me pretty much I don’t have a leg to stand on. We’ll be outta there in 90 days at the most, blah blah blah blah blah.”

King acknowledges he hasn’t paid rent for 90 days, because he can’t afford the new, higher amount. The landlord has extended the date to vacate from September to March 15, but that’s absolutely it. After 28 years, the Coltrane church has to move.

The Union Street real estate firm of Hill & Co. acts as property manager for the building. Agent Larry Stacy refuses to comment on any particulars of the current landlord/tenant negotiation, but does say that the church has had a history of delinquent rent payments, and that the new owner has made considerable financial concessions because the church serves the public. But when it comes down to the bottom line, the building is now a different property, with a different relationship to the tenants. And yes, he adds, the situation is unfortunate.

Steven MacDonald, the lawyer King consulted about the rental dispute, declines to discuss his former client directly, but he does confirm that commercial space in San Francisco is treated differently than residential property. Rent control does not apply to business space. And in this case, the Coltrane church is a business.

“To the people involved, it’s not simple, but from a commercial standpoint, it’s very simple,” he says. “Month-to-month is very difficult. When a new owner decides that they’ve got another use in mind, that’s it.”

San Francisco is experiencing an unprecedented commercial real estate boom. Spaces that once were considered disreputable are now being snatched up by high-tech firms and other companies that are benefiting from the strong economy. If a landlord buys a commercial building, and the tenants are renting month-to-month, if he thinks the market will pay more rent, he has the right to do just about whatever he wants. Even if that means posting an eviction notice on a kitchen that serves the homeless.

So the Coltrane church situation is pretty much over at this point?

MacDonald pauses, and says quietly, “Yeah.”

Bishop King eases his wife’s car onto Third Street, and slows as he passes a boarded-up tavern. He has been thinking about moving the church into this space, at least temporarily. It’s in the heart of the community it serves, and Muni will eventually extend rail service to this point. But he’s concerned that the tourist portion of his congregation might hesitate to commute all the way out to the Bayview.

We cruise past rows of residential housing. During Willie Brown’s recent campaign, King says, church members actively participated in spreading the word throughout this neighborhood. They helped re-elect the man. To them, he is the father of the city, and they are his children. So King says he went to City Hall to meet with Brown, and asked for assistance.

He stressed his church’s civic importance to the mayor, especially in terms of tourism. King envisioned a permanent home for St. John’s, where people of all faiths could worship, and take classes in what he calls “Coltrane consciousness.” The church would continue its outreach programs, hold a drum clinic, maybe even open a Coltrane college. Brown acknowledged that the church is popular with tourists. “If this is the place for their destination, then we do have to do something about it,” King says he was told by the mayor.

To Brown, doing something meant that if King wanted to raise money within the secular community, the mayor would graciously lend his name and his support. As he does with any major real estate development in the city. King doesn’t want to take government grants or tax money (constitutional restrictions on state support of religion would make a governmental role dicey, at any rate) and estimates that land, architects, and construction of a new building would cost about $10 million. No money has been raised yet.

King says he spoke briefly with developer Charles Collins, who plans to open a Blue Note jazz club on Fillmore Street as part of the neighborhood’s planned Jazz Preservation District. But even if the church could be somehow included in the planned development, such an arrangement could not start until far in the future. Ground hasn’t even been broken yet for the new club. And to King, the Western Addition is more lower Pacific Heights than the African-American community he wants to be aligned with. Besides, as he says, who’s gonna be able to afford to go to the Blue Note?

After the service, as musicians pack up their instruments, members of the congregation shake hands and say God bless you to one another. Behind the altar of the St. John Coltrane Church and up a short flight of stairs is a Victorian flat with kitchen and restroom. Paint is chipped off the walls, but each vertical surface features at least one photo or poster of Coltrane. Nobody lives here. The rooms are filled with clothing and instrument cases.

A handsome musician in a turtleneck sweater named Clarence Stephens stands in the hallway. He has coordinated the church’s food program for the past 11 years, and says between 35 and 55 meals are passed out every Sunday, with smaller numbers on Monday and Wednesday. All the food is donated weekly from Trader Joe’s and Rainbow Grocery.

Stephens ended up running the food program after dropping by the church one day to teach music lessons. To him, donating food is a way to help people and see the results right away. “It’s hard to give everyone a dollar on the street,” he says. “You be out of dollars by the time you get to the end of the block.”

In the kitchen, Bishop King’s teenage goddaughter Erinne Johnson stands over enormous pots simmering on the stove, serving up beans, rice, and vegetables into styrofoam containers. Hungry homeless people begin lining up at the back door of the flat. Someone drops the Coltrane album Impressions into a boombox, and a saxophone serenades a scene of controlled chaos. People are bustling about, bumping into each other. A child wanders underfoot.

“We need forks,” says Johnson, dashing about the kitchen looking in cupboards. “This is not good.”

“Not good,” says the child.

“Not good at all,” says Johnson.

“Not good at all,” repeats the child.

Johnson turns to face the first person in line, and hands him a container of hot food with an apologetic look. “You know what, I’m out of forks.”

“That’s all right, man,” says a tall man with a hooded jacket.

Plastic forks eventually materialize, and the homeless accept their food, taking it into the backyard to eat. In a month, neither the church nor the music of John Coltrane will be around to help make their lives a bit better.

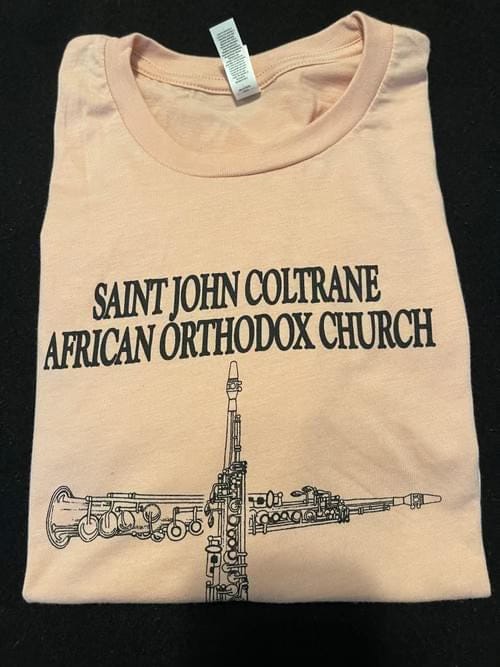

T-shirt design for Coltrane Church

'San Francisco is adept at fostering the creation of one-of-a-kind cultural landmarks, but not very good at hanging onto them.' - you nailed it, Sir. Brilliant and heartbreaking piece