Remember Webvan?

The original King of the Startups, and the $5 trillion lost in the dotcom crash

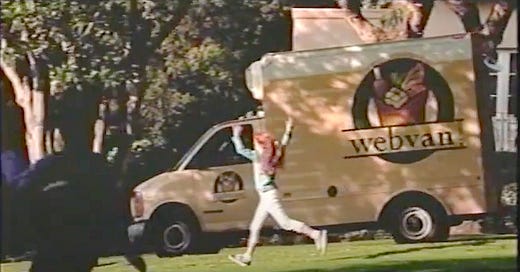

1999 ad campaign for Webvan

As the president flings tariffs like mudpies, the entire country is watching our economy tank in real time. It’s not partisan. This affects everyone, young and old, rich and poor, from Elon to my next door neighbor Lou. We’re in serious danger of a recession. And we’re all staring at each other wondering what’s next. Should I update my iPhone, before it costs $3,000? Do I postpone retirement until I keel over and die? We have been here before. Once in 2008, and further back, the funny-money days of the dotcom crash. This reminded me of Webvan.

Before Instacart, Amazon Fresh, or Uber Eats, in the late ’90s there was Webvan, the Grocery Unicorn. The company promised groceries in 30 minutes or less. The hype was astronomical, and investors elbowed each other out of the way to throw money at the idea. A nationwide network of warehouses, delivery trucks, and smiling employees who deliver food right to your door! Was it more expensive than just getting off your ass and going to the store? Of course. But the future was now!

Within a few years the dotcom crash brought everyone a harsh truth—their companies were not based in reality. (Also, some were just stupid.) The Nasdaq lost over 75% of its value, and $5 trillion in market capitalization disappeared. San Francisco turned into a ghost town, and U-Haul trucks carried the possessions of laid-off employees back to their parents’ houses. Webvan, the industry darling, king of the startups, was now a poster child of IPO excess, and the company washed away into bankruptcy.

How bad was it? In late 1999, Webvan went public and raised hundreds of millions. Fantastic! The stock doubled in the first day of trading, pushing the value to nearly $6 billion. Woohoo! A year and a half later, you could buy a share of Webvan for six cents.

CEO George Shaheen somehow walked away with a salary of $375,000, for every year remaining of his life. In 2010, Business Insider named him one of the 15 worst CEOs in American history. Shaheen’s lasting legacy, apart from collecting $9 million (so far) without doing a damn thing, is that business schools now study Webvan’s slide into oblivion as a classic example of how not to run a company.

I wrote a few articles about Webvan, this one first appeared in Business 2.0 in January 2001.

Throw a CD-ROM out your window and you’ll hit a person who has experienced the dotcom fallout, whether it’s job layoffs, getting fleeced in the Nasdaq, or watching an order screwed up by an online retailer. Whichever form it takes, each New Economy failure is then pounced upon by the media and reported with a knowing smirk: “We told you nobody would order allergy medicine online!”

All the more impressive it seems, then, to meet someone among the dotcom rank-and-file who’s completely unaware of—or completely at ease with—the industry’s death rattle. It’s like spotting a rare rainforest species. Or watching a presidential election in which every vote counts.

That person recently dropped by my San Francisco home, in the form of a driver for the online grocer Webvan. Two years ago, of course, Webvan was the poster child for VC funding, but now nearly $800 million later, it’s predicted to tank within months. And as this young man stood in my cramped kitchen, unpacking beer and dishwashing liquid and other items, I realized I had come face-to-face with a New Economy innocent.

Joe, you see, is all of 23, and has been behind the wheel of an official Webvan truck for all of two weeks, following a cross-country move to the San Francisco Bay Area. After some preliminary training classes and corporate indoctrination, the company unleashed him on Northern California with a frayed baseball cap, a van, and Webvan’s handy Palm invoicing unit for drivers. He makes two to three deliveries an hour.

Joe doesn’t exist in a complete vacuum. He knows that Webvan was started by Louis Borders, the man behind the Borders bookstores. He knows that the company recently bought out the competing HomeGrocer, and intends to offer service in HomeGrocer cities like Seattle and Portland. And he’s aware that Webvan hasn’t yet achieved its goals.

He tells me that the company’s cavernous 330,000-square-foot warehouse in Oakland, where groceries are stored and computer-assigned for delivery, operates at only a third of capacity. He admits that the groceries were once scheduled for delivery within a 30-minute window, and now it’s an hour. And he knows his stock options are worth less than my entire order.

As he processes my delivery, I mention that I once visited the Oakland warehouse, where a monstrous secret machine nicknamed the “DC” received email orders, and sent plastic “tote” buckets whizzing around a labyrinth of conveyor belts. Joe reports that the DC is still there and functioning, and asks if I want to keep the colored plastic tote to exchange it for my next Webvan delivery. I tell him no, because the deposit is $5 extra, and he shrugs. Apparently public opinion has turned about the totes. When the deposit was only a few dollars, people kept them in the garage. But now that it has risen to $5, fewer customers are hanging onto them.

At the bottom of my tote is a Webvan brochure thanking loyal customers and listing new developments, including a line of non-grocery goods such as toys, cosmetics, and electronics. The brochure also contains a letter from CEO George Shaheen, mentioning the many “remarkable changes” in service enhancements the company has wrought in recent months.

It excludes, of course, the kinds of remarkable changes that Wall Street analysts are picking on these days—that Webvan’s growth projects have been put on hold, that a Snickers bar is worth more than a share of its stock, and that the company is burning through $120 million per quarter, with the remaining $377 million predicted to run out within a year.

All that is news to Joe. He’s been told, he says, that Webvan hopes to turn a profit within a few weeks. It almost makes you cry to hear it out loud.

As for his stock option package, which will take four years to vest fully, Joe harbors no illusions. “I don’t think I’ll be here for that long,” he says. “But it was good that I got in when it was really low.”

What really gets me isn’t just that George Shaheen continued to collect money from Webvan, apparently until 2019 if LinkedIn is to be believed. It’s that so many other companies rushed to get him on their boards. Gee, it’s like basic competence has absolutely no connection to executive success…

I loved Webvan and was so sorry to see them fold. Every other house on my street had a yellow Webvan bin on their porch. It was awesome.