Olga Zilberbourg: Literature from Russia, Ukraine, t.A.T.u., & The Wizard of Oz

A conversation with the St. Petersburg-born writer and lit organizer

So Olga and I have known each other for some years, through the Litquake orbit and elsewhere. In 2023 I produced an event with Ukrainian author Andrei Kurkov, which was a fantastic conversation that Olga was kind enough to moderate. I’ve always wanted to talk with her more about growing up in St. Petersburg, Russia, and so we finally got the chance to chat for awhile!

Olga Zilberbourg is an award-winning writer and author of four collections of stories in Russia, as well as her recent English-language debut Like Water and Other Stories (WTAW Press), which Anthony Marra called “a book of succinct abundance, dazzling in its particulars, expansive in its scope.” Her writing has appeared in World Literature Today, The Believer, Electric Literature, Lit Hub, Alaska Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. She serves as a consulting editor at Narrative Magazine and as co-facilitator of the San Francisco Writers Workshop. She is also co-founder of Punctured Lines, a feminist blog about literature from the former Soviet Union. She is currently at work on her first novel.

So tell me about Punctured Lines, which is an excellent galvanizing force for writers who grew up in the Russian diaspora or former Soviet Union. How did it come to be?

In many ways it came out of publishing my book Like Water & Other Stories. It helped connect me to the community for which the book was written. But I didn’t know that. In all of my writing groups in San Francisco, I was usually the only person of my particular background. So I was always explaining my culture. Trying to not do that, but finding myself in that situation. When the book came out, I started promoting it on Twitter.

And that’s how I met Yelena Furman. She teaches at UCLA. She was born in Kyiv, and she lived in Moscow as an adult. She is a Slavic scholar, and studies women’s writing of contemporary Russia and diaspora writers. So she and I started getting into these conversations about Russian lit, and how it’s still represented by old men.

Old dead guys, right. Dostoevsky, Tolstoy.

Old dead guys. That’s who you think about when you think of Russian lit, right? And that image hinders a lot of contemporary conversation. There are two separate things, the diaspora writing, and the writing that we get in translation from the languages of the former Soviet Union. So she and I started Punctured Lines as a feminist project to look at both of those things, and to center women’s voices and underrepresented voices. We do stories in queer lit in that space. A lot of books that are very interesting don’t get enough publicity in the English-speaking world. For instance, Akram Aylisli, a Azerbaijani writer who writes about the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. He has this wonderful American translator, Katherine Young, who’s been promoting his work. So the blog provides me the space where it helps me to read and explore and think deeper about a topic.

You live in San Francisco, where the Russian immigrant culture has traditionally been concentrated in the “Little Russia” neighborhood out in the Richmond district. Some businesses have since closed, and people have been priced out of the city, or moved to jobs in Silicon Valley. And the Russian consulate was famously closed in 2017. This project that you founded and created, is helping foster this new post-Soviet literary community. And you’re helping organize more and more events to showcase these writers.

We all know about the existence of the amazing New York and East Coast-based literary community. Shteyngart, Vapnyar, and Bezmozgis in Canada. We know a lot of these writers’ names. Here in San Francisco, I would hear individual voices now and again, but there wasn’t a sense of a community. It dawned on me that it would be really useful if we started to get to know each other’s work better. I started to meet writers in workshops, little by little, like Sasha Vasilyuk, who has a new book. Masha Rumer, she came through our Tuesday night group once. So it’s this group of writers that we’ve assembled around Punctured Lines. A lot of them came to the U.S. as young children or young teens.

So how old were you when you left Russia?

I was 17. I came here for college, in Rochester, New York. I always feel like I’m in between generations. I didn’t come here as a child. I was on my own, but never fully felt grown up. I also came here of my own accord. It was ’96, soon after the fall of the Soviet Union. There were maybe three other kids at school who came directly from the former Soviet space. But there were some immigrant families there. Interestingly enough, later I learned that the poet Ilya Kaminsky was in Rochester at about the same time. But our worlds didn’t cross.

That’s a big thing, though, when you’re 17, to leave. This was during the glasnost era of Russia, which people were thinking maybe was a positive thing, finally?

Most teens in the U.S. leave home to go to college. The model under which we grew up in the Soviet Union is that you stay home for as long as possible, until you get married. It changed very rapidly, after the ’90s and in the 2000s, where people started to have more money and opportunities. But no, I don’t think people leave home to go to school. You don’t leave home in St. Petersburg, typically. And again, I can’t speak for the whole Russia. I’ve met a lot of people from different parts of Russia, and I really only know a very specific corner of it.

But when you’re 17, it’s a restless age, right? What was the reaction from your family and your group of friends in St. Petersburg?

It was really emotional. My parents really wanted to give me this opportunity to study abroad, to experience something very different. They pushed me to do it. Also, we are a Jewish family, so that is always in the back of everyone’s mind. If something goes wrong where we are now, you need to explore where else we can go. That was very much part of my thinking at the time.

Your family supported you in it. That’s great.

We got a brochure from the college with all of these different majors. I had no idea what to do. My dad and I studied it together. In St. Petersburg you get to pick between math or humanities, but I didn’t have that choice. By the time you’re 17, your path has been set a long time, and I couldn’t veer off the math path that I had been on.

So you’re on a mathematics sort of path, and then you would get married and have children in St. Petersburg.

Yeah, and probably become a math teacher! Because again, as a girl in the world, you know, it comes with a ceiling.

So when you’re growing up in St. Petersburg, what part of the world were you able to see as a child?

In the late ’80s, early ’90s, within my community, people hardly traveled. At least with children. So for me, I grew up with stories of my parents’ travels. They had been all across the Soviet Union.

Because of their professions?

They had a month off in the summer, and young people traveled. There were lots of opportunities, it was really cheap. My dad has amazing stories. He was a part of a rock band in his college career. My mom, who was not a part of a rock band, she also traveled quite widely. So I grew up with these dreams of traveling around the Soviet Union. We had family in Sverdlovsk, which is in the Ural Mountains, and I always dreamed of going there.

So when I had the chance to go to Ukraine in 2002 for a magazine article, I remember walking around Kyiv with my guide, and you could still see red Soviet stars on some buildings. I mentioned that when I was young, this was considered the symbol of the enemy. He grew up in Ukraine, and his response was, “Oh, us too.” That propaganda imagery just seemed like relics of an older era. Do you recall any sort of youth brainwashing going on?

Absolutely, you know. My family, I wouldn’t consider them dissidents in any way. They didn’t leave Russia, they stayed even when I left. They were dissident adjacent. My mother, as a Jew, couldn’t apply to the math faculty at St. Petersburg University. So she had to apply to a lesser university and become a radio engineer, a job that she hated. She worked at a radio center. Part of its mission was that they dampened the signals from Western media, like Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, the State Department-sponsored radio stations that were broadcasting in Russian language towards Russia.

There was a whole culture in the radio engineering community of how to circumvent that. People were designing ways of listening to these waves. People made their own radios, which was illegal, I think. So my mom started to get some information pretty early. But that didn’t get transmitted to children.

I grew up with a lot of fantasies about what the Soviet Union is and might be. But I spent my summers in the countryside with my grandmother. We did travel to Ukraine twice, when I was five and when I was 11. I remember seeing the dam, the Kakhovka Dam, that Russia just destroyed. I mean, I assume it was Russia. For me, Ukraine was the land of plenty. It was amazing.

Very much so. Very beautiful, green, lush. There were trees everywhere. The breadbasket country, right? It grew crops and fed many countries. And now it’s a war zone and a humanitarian crisis.

Yeah, yeah. It’s so crazy.

Do you go back to St. Petersburg? Do you still have family there?

Most of my immediate family left after 2022. So I haven’t been back since 2017. I started being very scared to go after 2014. I was pregnant with my first son, and that’s when Russia first attacked Ukraine, and it was scary. I don’t even know what I was afraid of. I spend a lot of time trying to figure out why I couldn’t explain to people what I was afraid of. That year, I said I’m not going to Russia. I went to Helsinki, and my family and friends came to visit me there.

Another crazy story. I mean, it’s not exactly my story. My brother was born and raised in Moscow, but his girlfriend’s parents were from Vietnam. She identified her first language as Russian. She spoke some Vietnamese, but not a lot. She identified as a Russian citizen. But didn’t have the Russian passport. She had a tough choice, you could either pick a Vietnamese passport or a Russian passport when you reach adulthood. Her mother had gone back to Vietnam by then. So she chose a Vietnamese passport. She was like the DACA kids here in the U.S. Basically you spent your entire life here, but you don’t have the papers to go with it. And so when she and my brother came to visit us in Helsinki, they didn’t let her go back to Russia. Russia didn’t let her in.

So they just stopped her at customs at Helsinki?

Yes, she had to spend a night in detention, which, you know, is just horrific. She and my brother ended up spending three months backpacking around Europe, not knowing what to do. Trying to appeal her case. My brother went back to close up the apartment and grab some stuff.

That’s part of the fear, that it could happen to anyone, at any time. I’m guessing the Gorbachev years were probably pretty tame in comparison to what’s going on now?

Well, there was definitely a lot of violence in the ’90s. For example, this is even later, my dad couldn’t leave his windshield wipers on the car because they would get stolen. So when he parked somewhere, he would have to take the windshield wipers off the car to go with him. I remember in his briefcase, he always carried a roll of toilet paper. If you ever needed to use a public bathroom, or a bathroom at a café.

When you went back in 2017, what struck you?

I used to go back every year, and for long periods of time, and do a little travel. Before the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s hard for me to speak about the times when I was a child. I remember my grandparents, even in the late ’80s, people already had stopped traveling, because it was scary. There were always stories about people stealing your possessions when you’re asleep on the train.

But in 2017, I was really on edge the whole time I was there, because you could really tell there’s a lot more police presence. There had just been another attack in the subway station in St. Petersburg. But also, in many ways it was very nice and beautiful, and a lot of practical things were made very convenient suddenly. You could go to a bureaucratic office and do what you needed without having to wait in a long line, or having to fill out a form three times by hand in a particular form of cursive, without a single mistake. If you made a mistake, you had to start from scratch. This is how it had been until it got electronic.

After you moved to the U.S., did you have any realizations about what Americans knew of Russian history and Russian culture?

There’s not a lot of mutual visibility, I would say. And it goes both ways. I always use this example. What is the War of 1812? To Americans it’s one thing, and to Russians it’s a completely different war, when Napoleon attacked Russia. Here, it’s about the burning of the Capitol building. But most people don’t fully realize that. The 1812 Overture was written for a different war. It’s Tchaikovsky writing about Napoleon attacking Moscow. That always amuses people to discover that.

Ha, that’s amazing. Why would Tchaikovsky be bothered to write an entire piece of music about a war between America and the British? That’s hilarious.

I think it’s a good metaphor. Our friend Tamim Ansary writes this book, Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes, right? And in a way, I feel like somebody should write a similar book, how the history of the world looks from the Soviet perspective. Though of course, there’s so many problems with that, because we don’t want to write Putin’s history of the world. Putin operates with a very particular history that partly comes from the Soviet, but partly rewritten for him, as the new emperor of Russia.

America’s perception of Russia is largely shaped by World War II and afterwards. When I was a child in the ’60s and ’70s, it was always the space race and the bomb. Looking at it through an American lens, those are the things we were taught through our media and the schools.

There’s also very interesting ideas of what censorship was like in the Soviet Union, what was allowed and what was prohibited. One story that I love and I’ve actually written about, and appeared on a BBC broadcast afterwards. There’s a Russian translator, Alexander Volkov, who rewrote The Wizard of Oz for the Soviet public, for the Soviet kids. But he didn’t write America out of it. It still begins in Kansas. In the first chapter, he amplified the plight of workers in Kansas. When we were kids, we even dug a hole in the countryside where I grew up, trying to get to Kansas, to the yellow brick road. So it’s strange. Even though America was built up as the Other, there was also a lot of dreaming and fantasizing about what America was.

Right. And pop culture eventually started to filter in?

Pop culture reached us later than the older stuff. I didn’t know the name Beatles until I was 12. My parents knew. It was part of the counterculture, but that didn’t get transmitted between generations.

Well, I mean, if your dad was in a rock band, he would have known about the Beatles.

Yeah, for sure. But this was not something that was played on the radio. And not something that my dad was sharing with his children.

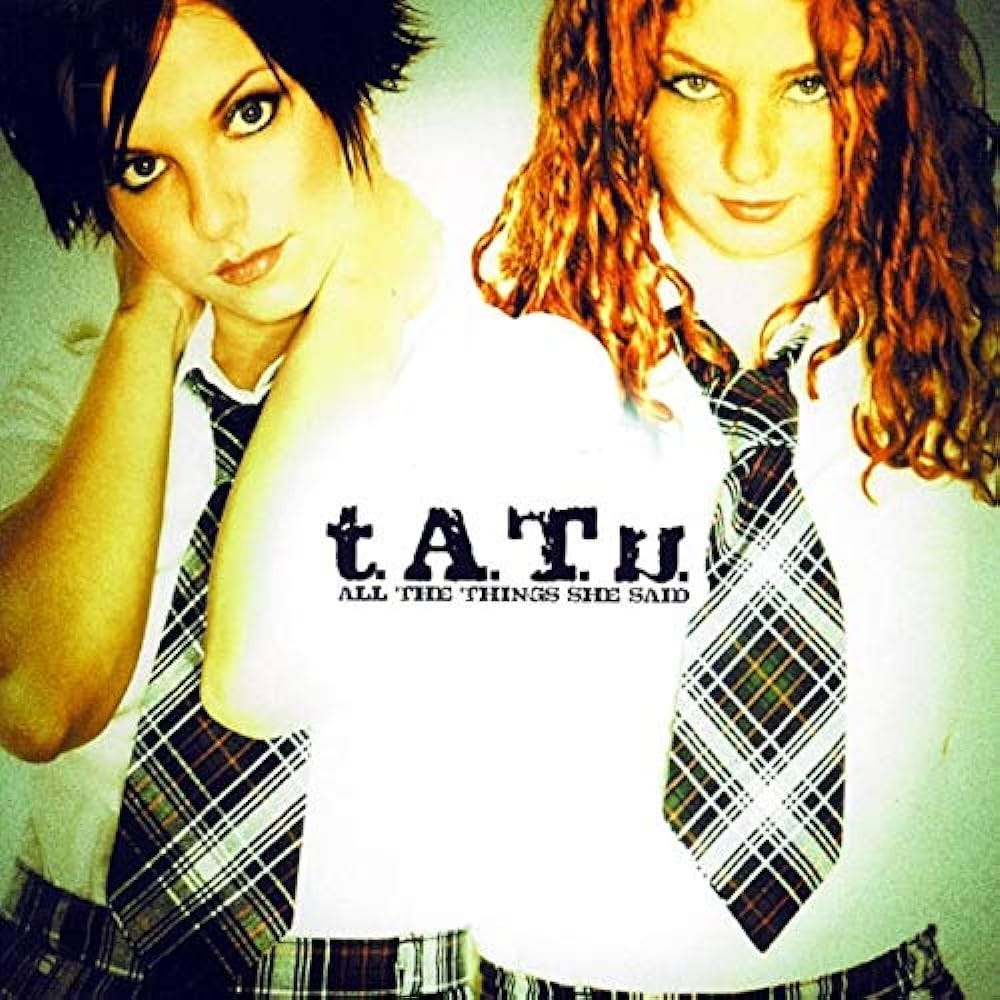

Wow. So, speaking of pop culture, when I was in Ukraine, I saw posters for this Russian music group, and it was so bizarre. They’re called t.A.T.u. You’ve heard of them?

Yeah, t.A.T.u. It’s the Russian word for tattoo.

Right, they were two women, and they were performing live in Kyiv. And it was so odd. On the posters, they were depicted as victims of abuse. They had black eyes, and bandages, and they’re staring at the camera. And I thought, that’s such a strange way to market music.

That band is so weird. All about that is so strange, because they became famous for being a lesbian duo. That was sort of their provocation to the country, to the world. Like we can perform this show of being lesbians.

And they would kiss each other on stage.

Yeah, exactly. But what happened later is, they both expressed some pretty homophobic stuff. They both married and had kids. And as Russia transformed from the possibility of openness and the idea of inclusivity, t.A.T.u. was at the forefront of the transformation back to being closed off.

They became the opposite of progressive in a way.

They were able to exploit lesbian identity as a performative thing. And once it stopped being useful for them, they just dropped it. To be acceptable, to continue to be okay with the regime, they had to formally renounce their previous connection with the queer culture. I would have to factcheck, but it felt like they had to renounce their youth fling as wrong, and maybe they were “corrupted by agents of the West.” Russia is fully embracing this spectacle of public denouncements these days.

What you’re saying seems emblematic of Putin’s regime. There had been advancements in freedoms, and now people have to adhere to an earlier, more strict sense of society.

Yeah, they had to be okay with the regime. I mean, honestly, all of these insane laws have one customer, and that’s Putin himself. Whatever polling is being done about what the people of Russia like or dislike, they have one customer and that’s Putin. I don’t know how Russians think, except I know what my personal friends think. There’s definitely good organizations who try to find out, for example, who supports these homophobic laws. I was following these stories closely, but I don’t remember whether these laws ever had popular support. Because popular support doesn’t matter.

Right. When Putin makes a televised speech and there’s a bunch of cabinet members listening in blind obedience, you’re like, okay, whatever. It’s all just for show. But when Navalny was speaking, there were genuinely hundreds of thousands of people in the streets. One of the truly great things Navalny did, was that he helped expose the secret Black Sea palace of Putin. Do you remember that?

I do.

That wasn’t words versus words, or who’s right and who’s wrong. It was photographic visual evidence of where your money went. A mansion that supposedly cost over $1 billion. It was impossible to deny in a way. That really hit me. How did you feel about that?

That investigation, they put it up in the middle of the pandemic. It felt like by then it was almost too late. I’ve had this feeling I was a Cassandra for a long time, that I knew Russia was an irreversible course from at least 2008. When Medvedev came to power, it was clear that elections were stolen and that protests were not leading to any shift. The only thing that Putin’s power has as a tool, is to increase police presence, ramp up enforcement and prosecution. They started specifically going after opposition when Navalny’s brother was jailed. And then Navalny himself.

It felt like there was this race. Here’s this new generation who believes in a different picture of Russia. These young people who didn’t know the past and who thought they lived in a free society, could travel, could build something new, could participate in it. That was really exciting and very invigorating.

But that young generation was in a race with the forces of the past, with the thinking of the men who wanted to control the power. By the time of that Black Sea investigation, it felt clear that this would only generate more repressions and more anger. And with all of that being said, the end of that sentence was Navalny’s death. Which is still painful to talk about. Because without people like him, who do give hope and show so much personal bravery, things would be even worse.

In the recent Navalny documentary by Daniel Roher, one of the things that was really striking about his personality, was that he was so open to anybody. In the middle of doing his work, he would take out a phone and just make a quick TikTok video and post it, and then get back to what he was doing. He recognized the value of communicating to a large group of people of different ages. There was something really positive about him.

He was able to do that in a genuine way. We tend to think of politics and politicians as more performative. But what he did came across in a very sincere, fully dedicated, fully passionate and dedicated way. I’m hopeful that maybe his wife Yulia can continue.

Women have a very large potential of organizing forces for opposition inside and outside of Russia. Right now some of the biggest sources of protests in Russia are happening in the wives and mothers community. Like the people who are being sent as meat to Ukraine—those wives and mothers have been attempting to organize and protest. They’re not specifically protesting for Ukraine. They may fully buy Putin’s narrative about Ukraine. But if you look at what are the forces of potential change, it’s the women themselves. And probably not the men who are being destroyed, either physically or psychologically.

That makes total sense. So, I wanted to ask you about the stories you prefer to tell. Although you moved to the U.S. when you were a teenager, your work so far feels permanently attached to Russia.

I know, it’s so weird.

Talk a bit about that. Of course this happens with any writer who grew up in another country, but Russia in particular seems to linger in the expat’s brain and soul.

For me, it happened in part because my family was there for so long. So I kept going back and thinking about it. Honestly, I’m not necessarily happy about this. I would love to find something different. I think my husband is getting really frustrated because his family moved out of Russia in the early 1900s, the Russian Empire. And as far as he knows, that place was already unlivable.

Do you feel a responsibility to continue telling these types of stories?

It’s something I can’t get out of, I guess. I think part of what I have from Russia is a different way of using my imagination. I grew up on the absurdist literature of the 20th century. There’s a very strong sense of how a story should be in the U.S. And I grew up with a different understanding of what is a short story, of what’s necessary and required for it to be a story.

Lyudmila Petrushevskaya is a more contemporary writer who writes powerful women’s stories. Her stories are also very multi-voiced. I wouldn’t say they have a lot of dialogues, but they include a lot of voices and narrative style. And they also introduce different subjects. She writes really contentious mother-daughter relationships, for example, that we don’t really see a lot of in the West. They’re presented differently. “I didn’t like my parents, so I moved away.” And the Russian story would be more like, “I hate my mother, but I am forced to live with her for the rest of my life while raising my children.”

Perfect. Okay Olga, thank you so much!

This is so fun too. Yeah, it was cool. Thank you.

Thank you Jack, for your excellent questions, speedy editing, and also -- beyond this immediate convo -- generally for everything you're doing for the SF writers community. It's so inspiring and nurturing. So much gratitude!

Now I will explore these other writers. Thanks.