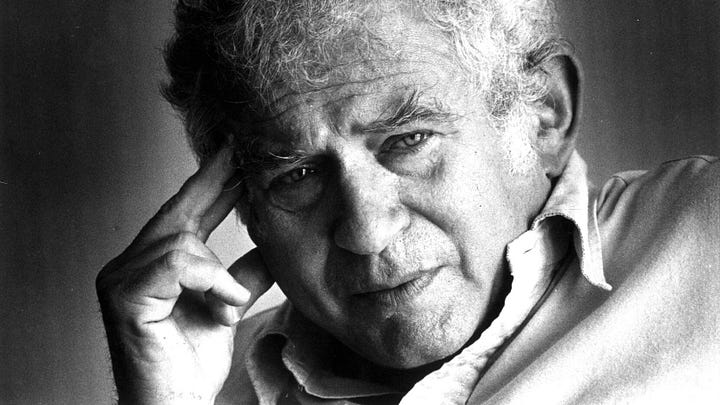

Mailer on Mailer

A rare glimpse into Norman’s Mailer’s 1995 book tour, as written by Norman Mailer

During a certain era, Norman Mailer was one of those writers whose name you saw quite a bit on magazine covers. He was also massively, absurdly self-centered. When he came to San Francisco in 1995, I thought it would be appropriate if Mailer covered his own book appearance…

Mailer on Mailer

By Norman Mailer, translated by Jack Boulware

It was a deceptively simple situation. The Writer, brandishing a formidable and long-awaited piece of research disguised as a bestselling book on the life of the young Picasso, on a publicity whistle-stop in San Francisco. The cool ocean air of Fitzgerald’s dark night filled his lungs, riffling those hairs that dangle protectively from the sweet scrotal sack, encased in which are the Balls, twin fortitudinal orbs responsible for groundbreaking novels, fistfights, and his penknife assault on his wife. The Balls, pendent, fully descended beneath his gray slacks, are, although the age of 72, still engaged in continual manufacture of his rampant tadpole seed, as if possessing a life of their own outside the rest of the man, insistent on fulfilling species propagation even if severed and flung against the stone wall of a Tijuana bullring. The Writer stood at a podium in a theater filled with the curious and adoring, including hipsters, scattered Negroes, and homosexuals. But no Harlem smoke, no devil swish. West Coast Negroes, West Coast homosexuals, WASPs, Irish, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, whites, all of which made up his audience, those readers possessed of an appreciation for the faculty of imagination. And his imagination was ready. He wanted to seduce the Bitch once more. She had had many San Francisco lovers over the years — Don Carpenter, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, even the rueful Kerouac and gadfly Caen — but he was still one of them. And there he was, back in town, holding the buttock of the lady in a guileless clutch. And he thought of the modern local newspaper jackdaws in sweatshop toil, farting up the hothouse beauty, the butter bilge, the toilet-tank prattle that constitutes the weakest and worst near-major newspapers in the country, their style reeking of stale garlic, mud pies in prose. And he thought, You don’t catch the Bitch that way, buster. You got to bring more than a trombone to the boudoir.

One of the oldest devices of The Writer — and in particular the Great American Novelist — is to bring his narrative (after much sighing and whistles of amazement from the audience) to a pitch of excitement and fevered discourse where the audience, no matter how cultivated, is reduced to a simple beast, tongue lolling in ravenous intellectual hunger, asking, “And then what? What happened next?” At which point The Writer, consummate cruel lover that he is, introduces a diversion, at once deepening the yearning of his audience, encouraging their appetite yet refusing to sate their pangs.

The Writer now pleads necessity. He will describe a momentary delay in reportage of his book tour appearance, because in fact he must. At this point he could not continue his presentation on the artist Picasso. The Writer became ensnared in a fit of coughing. He apologized politely, turned his head, and coughed again and again. The audience poised expectantly, as was their role, while a slide of a Picasso nude lingered on the screen behind him.

“Let me take a glass of water,” assured The Writer graciously. “That might ease the matter.”

The Writer reached behind the podium — a good, strong blond oak variation that reminded him of his National Book Award acceptance speech — located a glass and pitcher of water, poured himself a glass tumbler, and treated his affliction with nature's own agua.

“The treachery of the throat,” said The Writer to appreciative chuckles.

He had been here before. This cancerous dog-and-pony show was a leaden chess match this old man had come to play in his sleep. Nearly 30 books after his revolutionary 1948 novel The Naked and the Dead, he was once more surrounded with unformed minds seeking affirmation from the warrior, presumptive general, embattled aging enfant terrible of — as Terry Southern used to say — the “quality lit biz,” hard-working author, director of four feature films, past president of American PEN, twice winner of the Pulitzer, co-founder of the Village Voice, champion of obscenity, good friend to bourbon as well as gin, husband of six wives, head-butting party giver, and occasional hostess fondler. But tonight, onstage at the Herbst Theatre, wearing a forgivably rumpled blue blazer which embraced his barrel chest, simple shirt, gray slacks, and silver hair (not yet bald), in the zenith of his creative focus, presenting the nourishing fruits of another intellectual pursuit, he was not just a Jewish kid from Brooklyn anymore. He was finally in alignment with Arnold Toynbee and Bertrand Russell.

“Slide,” barked The Writer, and the projector clicked to a simple line sketch of a nude woman, her vagina rendered as a deft isosceles of carbon lead against paper — Picasso worked quickly. The Writer had always enjoyed articulating the vagina, discussing, observing, and eventually conquering it. He often trumpeted the idea — for instance, at his 50th birthday party he opened with a crude joke about the Oriental c*nt — but especially now, in these years of his sexual zenith. He liked the sound “vagina” made in its obscene echo off the walls and ceiling of the Herbst Theatre, and his face crinkled with the bratty smirk of the bagnio-bound jester. Picasso also directed much attention to the vagina, and this was where The Writer most felt kinship with the subject of his book.

“Slide!” he demanded, and plunged vividly into further analysis of the imagery, its prehistory, the location of Picasso’s apartment, the voluptuous models possessing “maws for vaginas.” At this point, he felt it essential to elaborate upon Picasso’s history of venereal diseases, concluding with raffish wit:

“That was no picnic.”

After interminable visual aids and excerpts from sources other than himself, The Writer finally read from his own bestselling book:

“One day with a model was enough — unless he wanted to start a relationship with her.”

The Writer stressed Picasso’s virtue of androgyny, suggested the edge of his impending personal dissatisfaction, compared his sexual history to the marijuana romances of the ’50s and ’60s, and after apologizing for showing the “only color slide of the Rose period tonight,” ended his riveting presentation to much applause: “I think I'm ready for dialogue with Wendy Lesser now.”

He sat across from her in a chair, she facing him in another identical chair, a table of dark wood between them supporting a plant and two matching glass tumblers of water, a woven rug with fringed ends their only barrier to the rough, raw surface of the theater stage below. She is editor of a modest literary journal called The Threepenny Review, also a Lithuanian Jew, as is he, and they both said so, and The Writer cleverly remarked, “I knew we were simpatico.”

He sat comfortably, his black shoes and black socks outstretched, his tough fighter’s hands resting in his lap, and when the question came, as it always did, he sat silently in the hunter's blind, shotgun to his shoulder, and squeezed the trigger:

“It's almost like the book chooses us.”

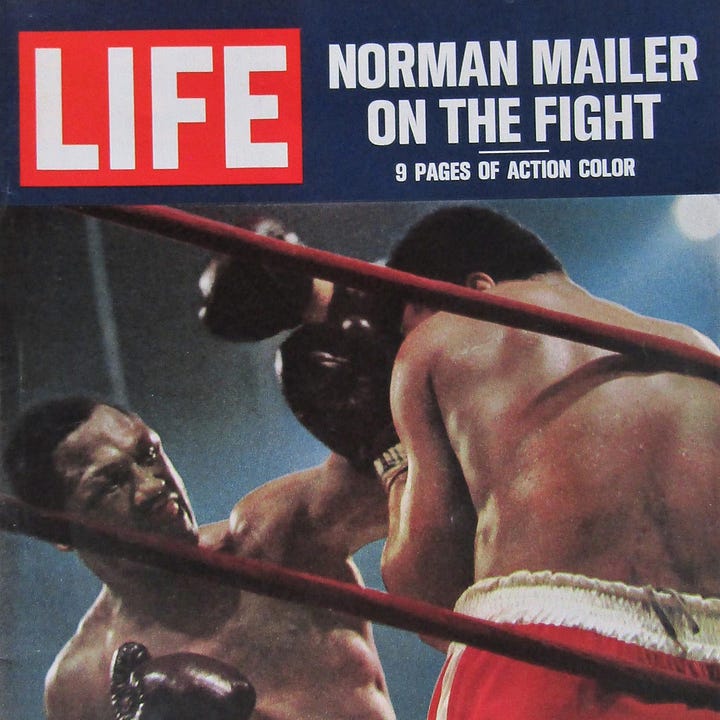

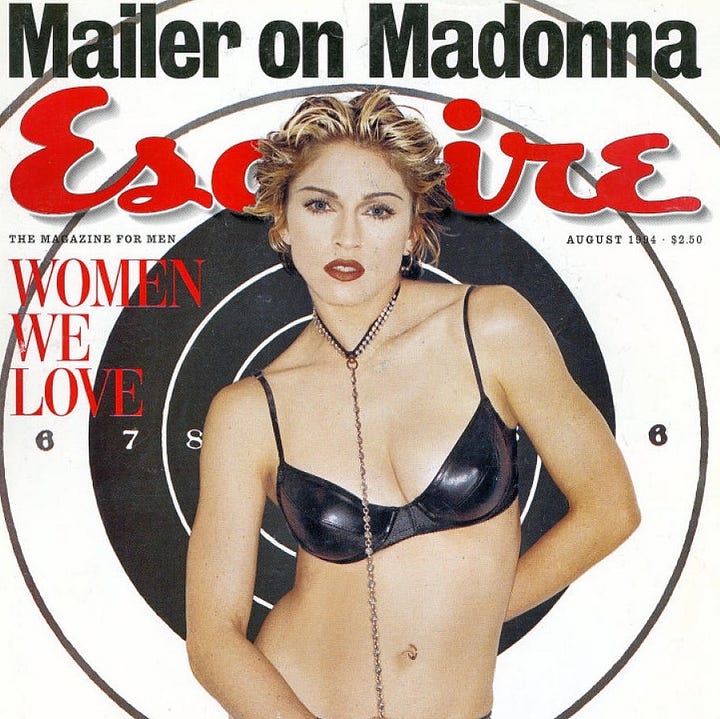

He was more comfortable now that the confines of his book subject were shed, and he could concentrate on what he knew best — himself, his writing, and, if need be, the maws of vaginas. He allowed he derived much pleasure from writing this book, and admitted he was drawn to the subject 30 years ago, but couldn't do it at that time. The woman nodded understanding, and he continued. A writer, if properly focused, can beam the resources of his imagination through different angles and subjects, as The Writer had done throughout his long and fertile career, from Marilyn Monroe to Gary Gilmore to the CIA to political campaigns and blood sports. He accused Gertrude Stein of being a fraud at the highest level, and compared her confused ramblings to the New Testament. He stunned his hostess with an abrupt reference to “getting it up the rear,” a powerful and lucid metaphor that shocked the crowd and assured his stature as America's preeminent radical intellectual. A short question-and-answer period followed, one audience member referring to The Writer’s “extraordinary book Harlot’s Ghost.” The Writer took delight in hearing this reader’s one-word assessment, and nodded not only to the adjective, but to the person who uttered it. The Balls pumped out another edition of seed, braced by the cool Fitzgerald air. He had seduced the Bitch once more.