Before we jump in, it’s apparently a busy month of lit events on my calendar. Here are links to where I’ll be appearing in San Francisco:

Oct 8 - Onstage interview with Doug Brod, author of Born with a Tail : The Devilish Life and Wicked Times of Anton Szandor LaVey, Founder of the Church of Satan. Green Apple Books, free, starts at 7pm, details here.

Oct 15 - Porchlight storytelling event for the Litquake festival. Swedish American Hall, $20 adv/$25 door, starts at 7:30pm, details here.

Oct 16 - California’s Fiercely Independent Literary Culture, as part of Litquake. City Lights Bookstore, 7pm, free, details here.

Oct 26 - The O.G.’s of Litquake, closing night Lit Crawl, The Chapel, 8pm, free, details here.

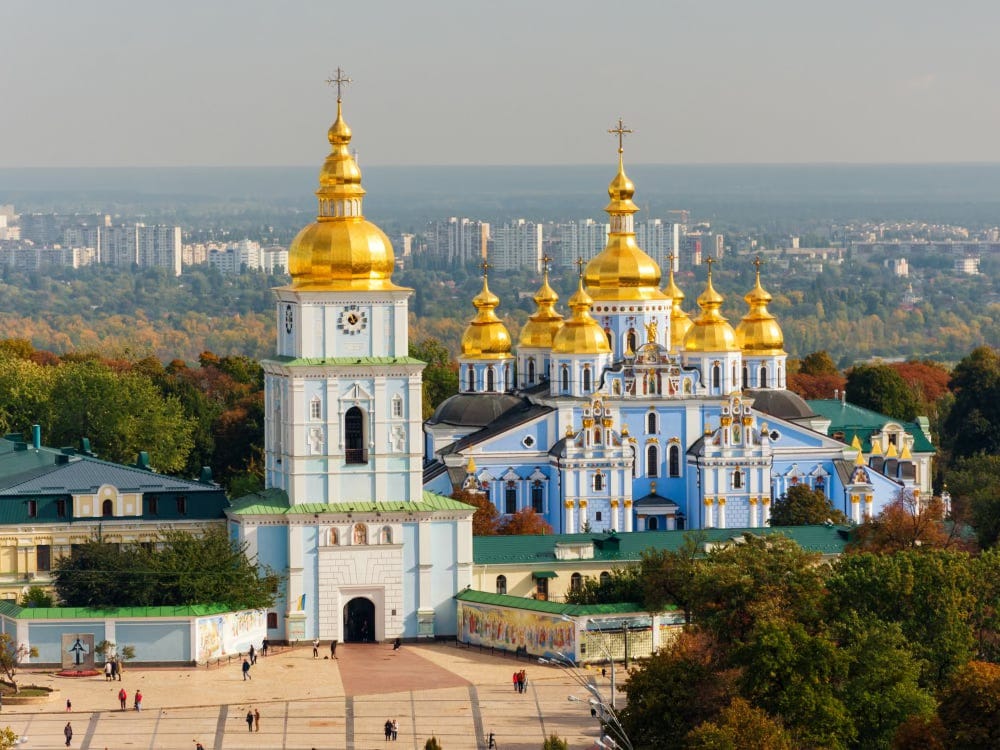

Okay, so obviously Americans are bombarded with election details at the moment, and among the topics tossed around is whether the U.S. should continue providing aid to Ukraine, to help its ongoing war with Russia. The past two years of destruction have been brutal to watch, especially because I was able to visit Kiev before the invasion, and witness a very different city. In 2002 Wired magazine sent me there to write about the looming criminal threat of that era: CD and DVD piracy. Which seems utterly ridiculous now, but back then it was driving the world’s entertainment industries into a full-blown panic. The U.S. was threatening Ukraine with millions in economic sanctions, unless it stopped producing and distributing copycat disks. I interviewed smuggling cops in London, Ukrainian government officials, and a diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Kiev who I’m pretty sure was a spy. The story got trimmed because some editors left the magazine, and there was so much extra material I thought I’d share more of it here. (Photos are from today’s internet.) Keep in mind this was 2002, and much of what I describe may no longer even exist. At that time, Kiev was a beautiful city, relatively stable, pleasant, and kind of wacky. It wasn’t perfect, but people were proud to be Ukrainian. Not one person I met had any interest in being attached to Putin’s Russia.

An old man stands on the sidewalk, holding out his hand. A small cloth is spread in front of his feet, with two carrots and a large onion. Twenty feet away, a man with a monkey on his shoulder approaches pedestrians, offering a Polaroid photo with the monkey. In an outdoor plaza, an orchestra sits in folding chairs, playing traditional patriotic Russian songs, accompanied by a chorus line of cheerleaders shaking pompoms. Underneath the street, in an empty subway tunnel, a woman sings opera along with a boombox.

It’s impossible to prepare for the peculiarity of downtown Kiev. There are no Ukraine travel books in English. The U.S. Embassy warns visitors not to use credit cards or ATM machines, not to walk alone at any time, to watch for muggers with guns, and go straight home to your hotel after dark. Despite all this, I am now here.

My main contact is Andrey Dakhovsky, a tall thin Ukrainian guy with a degree in nuclear physics, but since there’s no jobs he runs the Kiev office for Universal Music, distributing the latest releases by Bon Jovi and Eminem. We take a walk down Khreshchayk Street, the main thoroughfare. Kiev’s had a long history. It was the original capital of Russia, and has been a trading center for over 1,500 years. After World War II, when the Nazis blew up most of the city, it was rebuilt as a combination of Spanish architecture and good old Soviet gray slabs.

Several office buildings are decorated with red stars and hammer and sickle logos. I mention to Andrey that these images seem odd, because in America we were indoctrinated to believe Russia was the evil enemy. “Oh, us too.” he says, as if it couldn’t be more obvious.

He points out a giant metal sculpture, in the shape of a rainbow, which spans over the street. The People’s Friendship Arch was erected in 1982 to represent the friendship between USSR and Ukraine, and underneath the titanium span sits a bronze sculpture of a Russian and a Ukrainian worker. [The sculpture was dismantled in April 2024, the remaining arc has been renamed Arch of Freedom of the Ukrainian People.] Surrounding sidewalks are lined with concrete blocks about waist-high. Once they held 13 flags, one for each Russian republic. Now they’re filled with cigarette butts and candy wrappers.

Kiev’s statues of Stalin were torn down after 1991, but I do observe a few of Lenin, one of him leaning forward as if walking into a headwind. The most popular statue by far is of a Cossack warrior on horseback, whipping a spiked club over his head. If Ukraine has one national symbol, it’s the hetman, a fierce soldier who led troops into battle. The club is called a bulava. You see toy versions of bulavas for sale on the streets.

Because Russia was the enemy for so long, we Americans have no frame of reference for this culture, no context other than James Bond villains, a few anorexic gymnasts, and the old Bullwinkle cartoons. Every single second in this city yields new information. The only thing I know about Ukraine is Chicken Kiev, which I’m told nobody ever eats, and the Beatles lyric about Ukraine girls really knocking me out. And indeed the people are attractive. Teenage girls stroll the streets braless with short dresses and G-string thongs, accompanied by their mothers wearing the same. It’s a warm day, but wow, it seems pretty overt to my American eyes.

Some of these girls are gathered around a tossled-hair kid, sitting on the street curb, singing and playing acoustic guitar. The girls nod and sway back and forth. As we get closer, I hear him singing, in English, the Nirvana song “Rape Me.”

A few months ago, Andrey produced a free concert in downtown Kiev for 10,000 kids. The star attraction was a pop group from Moscow named t.A.T.u., two 16-year-old girls who dress like school sluts and tongue-kiss each other onstage, while water is dumped over them. “Eez just an image, nussing more,” he tells me.

Andrey has arranged for me to meet his wife and two sons for a drink at an outdoor café in front of the Dnipro Hotel. We sit and chat, the boys fidgeting. Above our heads are the windows of the Millenium Strip Bar, attached to the hotel. It’s still afternoon, and the dancers are already gyrating, visible from the street. Andrey mentions that when the musician Sting was performing in Kiev on tour, this strip club was supposedly one of his favorites.

I notice that Kiev has several new churches, some so recent their lawns haven’t yet grown in. Andrey explains that the mayor’s brother is a contractor, and therefore more churches were built.

So why is everything so corrupt, I ask. Why is it such an established way of life? “In the old Soviet ways, Uncle Joe took care of everything,” Andrey says. “People never learned to have responsibility. An old Russian saying is, cheat or be cheated.”

I get back to my hotel and meet up with Nikolai, my photographer. Nikolai is from Moscow, and was formerly a Bosnia war correspondent, until his partner got blown up in front of him, and he crawled off the road into the bushes. Now he shoots for magazines. We’re staying at the Hotel Ukraina, an old ornate building built in 1908. In a month, the Hotel Ukraina will change its name to the Premiere Palace, and just to make sure everyone is confused, the Hotel Moscow will then change its name to Hotel Ukraina.

The next morning we take advantage of the complimentary breakfast, in the eighth floor restaurant overlooking downtown. Like everything else in Kiev, there’s a continual undercurrent of shamelessness. A screaming Santana guitar solo plays softly, and we watch businessmen stand in line at the omelet station, accompanied by slinky women in animal-print catsuits, teetering on high heels. Everybody needs an omelet. Nikolai takes a bite of bacon and smiles: “Prostitutes.”

Soon, we’re standing on a busy street corner, looking for a taxi. Kiev gives us three options: Official cabs, gypsy cabs, which are really beat-up official cabs driven by scowling chainsmokers, and if all else fails, you can just flag down a working joe on his way home from work. A gypsy pulls to the curb, I slide into the trash-filled back seat next to some dirty clothing, and Nikolai jabbers at the driver in Russian. He nods and speeds away.

We drive through several downtown blocks, passing an incredibly ornate Opera House, and end up in a tree-lined district of brick buildings. We’re here because one of these buildings is the former Rostok missile parts factory.

Much to the outrage of international corporations, Rostok has repositioned itself as one of the world’s largest bootleg CD plants, cranking out thousands of pirate disks which end up smuggled around the globe. Most of these operations have been shut down, but Rostok stubbornly continues. Nikolai and I want to interview a CD pirate and get some photos. We pay the driver to wait, and walk up to the entrance.

Security cameras are mounted on the building. The factory’s lobby looks very deliberate, as if they were anticipating an inspection. Glass display cases present a benign selection of food processor blades, electrical motors, a toaster, a blender. Nikolai begs the receptionist if we can go into the factory and take photos of them making CDs. It’s a ludicrous request, but hey, you have to ask. The woman shakes her head and says in Russian, “You have to leave. The Americans are trying to shut us down.” They argue for a bit, and she points angrily to the front door, and Nikolai turns to me and says, “Let’s get out of here.”

We walk outside just as a black Mercedes roars around a corner and pulls to a stop, the driver watching us and speaking into a cell phone. A few months ago, a Ukrainian journalist was found beheaded just outside the city, for writing stories critical of the government. My passport is at the hotel. My language skills are limited to “da,” “nyet,” and the Polish words for “chocolate” and “potato.” This is not good. Nobody knows where I am.

The driver stares us down, then mutters into the phone and drives off, performatively screeching his tires like it’s a TV show. Nikolai looks at my worried face. We approach our parked taxi, and he suddenly says, “Our driver’s throat is slit!” He bursts out laughing. The driver is calmly reading a newspaper.

Our next stop is Petrovka, an enormous outdoor market in the poor section of Kiev. The average Ukrainian makes less than $100 a month, so this is where most of them do their shopping. You can buy everything from books to CDs, clothing, household goods, all of it pirated, with phony labels. Police raid it occasionally, and haul away boxes of bootlegged CDs, and the next day all the stock has been replaced.

It’s a hot sticky afternoon, the air is filled with the stench of sweat and diesel exhaust. We wander the stalls, and I spot a pirated CD of the band Metallica. To a local it appears the same as any bogus disk of Eric Clapton, Sting, or Whitney Houston. But as an American, it’s a rich irony that the group most responsible for putting Napster out of business has been ripped off to an unimaginable extreme. Nine albums on one CD-ROM. Cost: three dollars US. Of course I buy it.

We return to our hotel and then walk down Khreshchayk Street for a beer. At a bakery, elderly women stand in line for bread, clutching their greasy bills of hryvnia currency. Boisterous young people pack the sidewalk cafes, wearing leather jackets, or Nike, Adidas, and Disney logos. Everyone is talking and smoking. Pockets of loud laughter. Occasionally, a German-made car with tinted windows inches through the crowd.

“Look at them,” says Nikolai. “Ten years of freedom, and they’re still celebrating.”

We meet up with one of Andrey’s employees. Dimitri is a local record producer, about 30, with a hip haircut and the easy smile of a car salesman. He carries a wad of American cash in his pocket, and his cellphone rings constantly. I wonder what scams he’s running on the side. He says he has something to show me: “I take you to the Buddy Guy Blues Club. Lez go. Eez American, you love it.”

We walk down a flight of stairs, underneath a photo of blues guitarist Buddy Guy. I ask Dimitri if he knows who Buddy Guy is. He shakes his head no, smiling, and beckons me into the bar, where he assures me, we will see really great American blues music. Neon beer signs hang on the brick walls. The room is virtually empty. Onstage at one end, a group of high school musicians finishes singing a pop song in phonetic English, and a handful of family members applaud from their stools. Dimitri gestures around the room and shouts, “Eez this great?”

We go back upstairs to the street, and Dimitri suddenly announces he has to do some business, and leaves me with his girlfriend Nataski, an 18-year-old student who is attractive but shockingly thin, she appears to weigh about 56 pounds. I sit with her at a wobbly plastic table, and she asks me in English, “Is it true, in America only poor people eat at McDonalds?”

I’m a bit speechless. That never occurred to me before. At the two McDonalds in Kiev, prices are too expensive for the average Ukrainian. I imagine teenagers going to their version of the prom, and the big night on the town culminates with a Big Mac and fries.

One taxi ride later, Dimitri, Nataski and I walk across a footbridge of the Dnipro River to a little island lit up with nightclubs, discos and casinos. This is where the new money parties, a resort-blaze of lights and loud techno music. The sun has set and it’s now dark. As we approach the Sun City disco, Dimitri mutters, “Don’t say anything, we’ll have to pay if they know you’re American.” I put on my best Eastern European scowl, and the doorman allows us in without charging.

We grab drinks and walk down to the sandy shores of the river. Guys and girls are shedding their clothes and splashing around in the water. They ask me to take their photo, and I click a few shots.

I ask Dimitri, “Isn’t this the same river that flows through Chernobyl? This is the water that flows through the world’s worst nuclear disaster zone, and people are swimming in it.”

“Eez been tested,” he says. “The government says eez perfectly safe now.”

You have to appreciate the post-Soviet surrealism, the absurd collision of old and new. And I know Ukraine is only ten years old, and it came out of this culture of no responsibility. But I still can’t get a bead on why. I want to see something that will help explain it. And I don’t know what it is.

The next day, I’ve got a few hours before my flight and take a cab to the Chernobyl Museum. Outside the entrance, children are buying ice cream from a cart. The doorway is decorated with Russian-language flags and signs.

A main exhibit room is covered from ceiling to floor with photos of the workers who died. A tour is in progress, somberly watching a video monitor. It’s pretty sad. When the nuclear reactor exploded in 1986, the Soviet government waited several days before telling its own people what had happened. The world learned of Chernobyl only when a nuclear plant in Sweden noticed the high levels of radiation. Citizens wandered around in nuclear fallout so hot, it registers on the videotape as white spots. A child is shown playing outside in a yard, and it looks like it’s snowing. Fortunately for Ukraine, the wind blew most of the radiation north, and it landed on Belarus, where for years afterwards, babies were born with no eyes or arms.

I wander around the room. Display cases show diaries of plant employees, medical reports, a horribly mutated dog. Horror after horror. A separate room is covered with children’s artwork of the disaster. It’s like the museum’s creators demand that you wallow in the tragedy, relive the deaths, keep the wounds open forever.

But it strikes me that there is no explanation for the explosion, anywhere in this museum. In America, there would be a detailed diagram of exactly how the accident occurred, who was at fault, how it could be prevented in the future, how a normal plant is supposed to operate. A table would be piled high with anti-nuke flyers and solar energy brochures. Here, nothing. Apparently, Chernobyl just…happened. It’s the ultimate paradox, the denial of responsibility, the culmination of decades of Soviet rule, when Uncle Joe Stalin would take care of everything.

I request my interpreter to ask the museum staff why the explosion occurred. She has a long, five-minute conversation with a curator, then walks back and says: “It’s believed that there are three reasons. The main reason…” She searches for the word in English. “...is negligence.”