Joel Selvin: Drummer Jim Gordon, S.F. History, and the Bay Area Music Lightning Round

A conversation with the legendary San Francisco rock journalist Joel Selvin

Joel Selvin is a San Francisco-based music critic and author known for his weekly column in the San Francisco Chronicle, which ran from 1972 to 2009. Selvin has written more than 20 books covering various aspects of pop music—including the No. 1 New York Times bestseller Red: My Uncensored Life in Rock with Sammy Hagar—and published articles in Rolling Stone, the Los Angeles Times, Billboard, and Melody Maker. He has written liner notes for dozens of recorded albums and appeared in countless documentaries. His most recent books are Sly and the Family Stone: An Oral History, Arhoolie Records Down Home Music: The Stories and Photographs of Chris Strachwitz, and Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon.

I’ve been reading Joel Selvin’s writing ever since I moved to San Francisco in 1983. We’ve known each other for a number of years from Litquake festival events, as well as the stray party here and there. But it wasn’t until I launched this Substack that it occurred to me, Jesus Christ, I should just interview this guy. He’s got tons of stories. And, he just published a new biography of the rock drummer Jim Gordon, which is easily one of the best things he’s ever written. We go pretty deep and I hope we didn’t get too far in the weeds. There’s lots of links and photos, and if you’re curious about Jim Gordon, plenty of playlists await you on YouTube and Spotify.

So you grew up in Berkeley, dropped out of high school, and started working at the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper in 1967. You were a copy boy at first. How does one get to become a copy boy?

Copy boy positions in those days were all nepotism. I grew up in the Berkeley hills adjacent to the Scott Newhall family. My older brother went to school with John Newhall, and our parents were friends.

And Scott Newhall was editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, famously known for a front-page story about how terrible coffee was in San Francisco, with the headline “A Great City’s People Forced to Drink Swill.” That was legendary.

When Scott Newhall took over the Chronicle in 1954, it was the fourth largest newspaper in SF. In 1959 it was number one. He was a swashbuckling, old fashioned attention-getting newspaper editor who sent the outdoorsmen in his family out to see if they could survive a nuclear holocaust. As you say, the series about coffee. He had a series about clothing naked animals.

Oh yeah, the Society for Indecency to Naked Animals. With Buck Henry, who was an actor hired as a spokesman trying to put pants on a baby elephant at the San Francisco Zoo.

That was a George Draper piece. George Draper was in the Abraham Lincoln brigade before the war. Fought the fascists in Spain. And was just the most amazing kind of guy. The sort of person that populated the front page in that world. He rode his bicycle to work from Sausalito, he was an incredible old-time newspaper guy.

So you arrive at this newspaper when you’re 17. Did you foresee the future, where you’re going to be the music critic for the next 35 years?

No! The work of a copyboy—much of your time was spent at a table, folding carbon paper between newsprint, so the reporters wouldn’t get their fingers dirty. It was very menial chores. As a result, I saw the whole newspaper industry. I’d been in the stereo room, I operated the wire machines, all over the building I knew what was done where. When the presses started up, the whole building would start shaking.

I was really taken by the romance of the whole thing. I remember walking into the city room the first day, and there were no trash cans. People just threw things on the floor. And sometime after midnight a janitor would sweep up. And start over the next day. Because it was pointless. I was like wow, this is a giant playpen.

And then, I started getting on the guest list at the Fillmore. And that was, as Lenny Bruce would say, getting a shot of morphine straight in the stomach. I mean, Cream, Hendrix, you name it, I saw them.

During this time, I’m guessing the newspaper world was still largely a suit and tie affair? And you were the young hepcat from Berkeley, walking in and looking around and thinking, okay, who smokes pot, and who doesn’t? That was important back then.

There was a creeping hipness in the younger ends of the reporters. The copy boys were all older than me, they were all well culturated. All that stuff was leaking into everywhere in San Francisco.

What was your first review?

I was in the office, as a copy boy, and the editor of the Datebook wanted somebody to go review, I swear to god, Myron Cohen and Sergio Franchi at the Circle Star Theater. Myron Cohen was an old-time Jewish comedian, not even in poor taste, he was clean and dull. And Sergio Franchi was this Italianate pop singer, in the mold of maybe an Al Martino or something.

What a weird bill.

Totally weird bill. And you know, that show business was already totally over by that time. it was like Totie Fields-era stuff. But that was my first review for the Chronicle. This little freelance article.

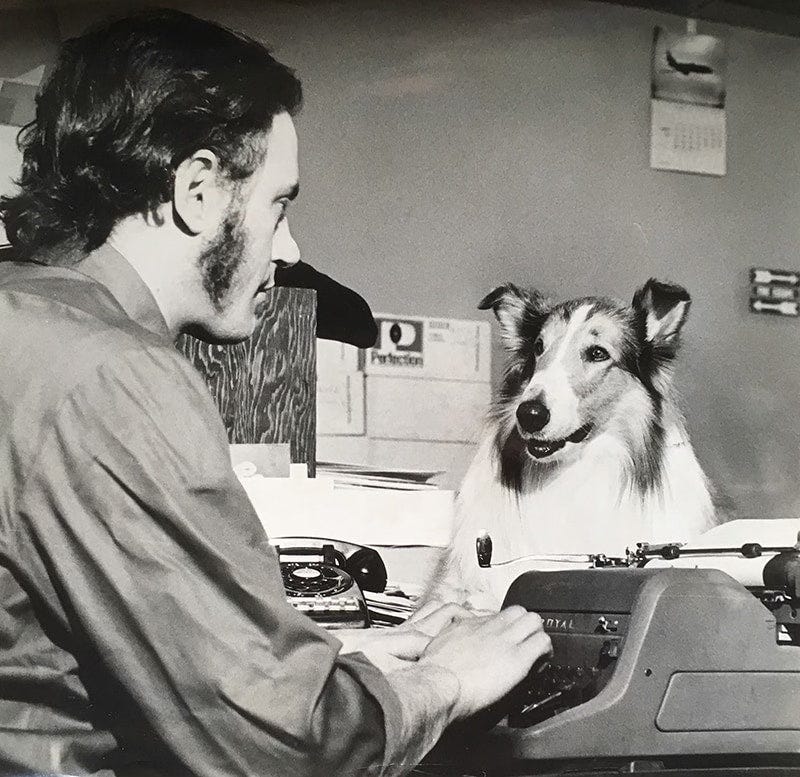

Tell me about the Chronicle columnist John Wasserman. You became his assistant for a time. I first became aware of him in a used bookstore, a collection of his work for two bucks. As a fledgling newspaper columnist, I devoured this, realizing what could be possible. This sense of pure freedom, with a crazy twinkle in his eye. He once interviewed the dog Lassie, and the Chronicle ran a photo of the dog sitting on his desk in the newsroom.

He had no problem doing things like going to the Cow Palace to review the Osmonds concert. I actually found this review online: “The Osmonds originally tried to make it in show business as singers and musicians. When it finally became clear that this was an impossibility, they formed their current act.”

The Osmonds review. I’ve stolen that line, that Donny Osmond “is as cute as a Presto log.” John came from the aesthetic that would be best described as the early ’60s Playboy magazine. Light jazz, stereo hi-fi nut, that whole style. Cocktails for sure. And cigarettes. He didn’t really grok the new rock, although he understood that it was popular and important. He was much more inside the Al Jarreau, Kenny Rankin kind of stuff.

He started out as an impolite film critic. Which he was brilliant at. His review of Texas Chainsaw Massacre is genius. There was a film critic at the Chronicle who handled all of the Hollywood movies, so John started doing drive-in movies, and B-movies, stuff like that. Being rude, and mischievous, and funny. He had an incredibly good sense of humor. He brought this underpulse up into the paper where it hadn’t really been much before.

I can’t begin to tell you how many things John taught me. He took me under his wing and mentored me. He was 11 years older than me. I remember driving into the San Francisco airport, we were going down to L.A. to see the Stones and come back the same night. Sign says “Sorry, level full.” And as we drove past that sign he said, “Signs, Joel, are for assholes.” I mean, I don’t know where you’d learn this stuff otherwise!

At that point I proved myself very useful, and also I was out at Winterland, writing reviews of the contemporary rock scene, so I ended up with a position at the paper of a pop music reviewer, starting out part-time. I was 22.

Did you know the Chronicle political cartoonist Robert Graysmith, who wrote the definitive book about the Zodiac killer? When I met him, he had just published a book on the murder of actor Bob Crane.

One of the weirdest, most wonderful guys that worked there, and the newspaper was full of them. He sat back in the corner and watched everything. He was an obsessive researcher. He was all over the Zodiac thing. That’s how he ended up in that movie. And that guy who played him, Jake Gyllenhaal, really kind of channeled Graysmith. Paul Avery was just another incredible character.

Avery was played by Robert Downey Jr. in the Zodiac film. Before the movie came out, I had a vague inkling that he was the Zodiac Killer’s contact at the Chronicle. I met him only many years later.

Did you meet him after he got sober?

He was in a wheelchair, and had an oxygen tank. This was at Pier 23. I didn’t have a chance to really talk to him.

He was fading. I knew the wild and crazy Avery. We snorted plenty of blow together in the men’s room. He wrote what he thought was happening, and then his sources would call in the next day and correct him. Avery was unhinged. And just a force of nature.

Can you talk a bit about Ralph Gleason? I first heard of him when I subscribed to Rolling Stone at age 12. The issue came in the mail and the entire magazine was a tribute to him, he had just died. I was reading these long articles and I realized, I have no idea who this guy is. Obviously I later learned his importance, that he helped launch Rolling Stone, co-founded the Monterey Jazz Festival, testified for Lenny Bruce in court. I also loved watching episodes of “Jazz Casual,” the music program he hosted in the ’60s, which was produced and recorded here at KQED. What was your memory of him?

I read every column Gleason wrote in the Chronicle, once I was infected by the music scene, at age 15. He was the absolute window into what was going on in San Francisco. The radio stations were coming along, but they weren’t really there. So at the bottom of his column, he would just drop in a bunch of one-sentence plugs for gigs coming up. And that’s how you found out what was going on in town. He told me years later, he put those in there because he knew that’s what people would read first.

He was one of those names you always saw in jazz liner notes, he was sort of the west coast guy.

There were three guys: Nat Hentoff, Leonard Feather, and Ralph Gleason. Before there were books and magazines about this shit, where do you go, in 1964, 1965? You go to the record store after school, and you read liner notes. I used to stand in Discount Records on Telegraph Avenue, and read Hentoff, Gleason and Feather to absorb this information which was unavailable elsewhere. The history of the music was contained on liner notes.

They also gave context to the music. People didn’t know how to describe jazz. Other kinds of music, you could at least quote the lyrics, but jazz writing, it’s a totally different thing.

Writing about music is always tricky. Especially when you have to come into the area where you describe what people hear. That is worse than describing smells. Because it’s so vague, and so subjective, and the terminology is so imprecise. When I come up to a place in my writing where I have to go into the music, and describe it, to me it’s a major alert. And I do it as carefully and as fast as I can, and get out of there. No eloquent expansions, and rhapsodic—no, let’s just get this over and done with.

My rock journalism era was Circus and Creem magazines, where I first became aware of the music of that time, punk, and glam, and the larger swath of ’70s rock. Very different approach than Rolling Stone writers. Very stylistic freedom, personalities like Lester Bangs and Nick Tosches.

Tosches, man, that guy writes better than anybody. He was better than everybody else.

His book Dino, the Dean Martin bio, is just incredible. And it still holds up.

Okay, I’m in New York, working on the Bert Berns book. I’ve just gotten there, it’s my first week in the Village, and I’m going to dinner with a friend of mine. There’s a guy at the bus stop, clearly intoxicated, almost about to pass out. And behind him, some model is rubbing his neck. That was Nick Tosches. And my friend knows him. We didn’t say anything that night. but we’re out a couple of days later in the neighborhood, and run into him. He’s just a fantastic guy. Just a cauldron of knowledge and intellectual curiosity. And wit and wisdom. He was amazing.

Rolling Stone launched in San Francisco in 1967, and throughout the ’70s grew into this legendary repository of rock journalism, and journalism of all kinds. The contributor list is long, from Ben Fong-Torres to Cameron Crowe, Hunter S. Thompson, Joe Eszterhas, Tom Wolfe, etc.

It was rich in the ’70s, really rich. And then by the ’80s it got sort of New York-y. Jann [Wenner] called San Francisco a “provincial backwater.” He showed up in New York, and within a year his picture appeared in the Chronicle escorting Carolyn Kennedy to Studio 54, and it said, “Carolyn Kennedy with unidentified escort.” Ha ha ha ha!

I remember seeing him play himself, a bit too eagerly, in the movie Perfect. One line in particular was just ridiculous: “Mikey Douglas is in town, and I’ve got the cocktail flu.”

Yeah, that was just—he was gone. There was too much ego, and too much, “Hello Mick,” you know.

Before it moved to New York, the offices of Rolling Stone and the Chronicle, we’re talking south of Market, were maybe only 5-7 blocks apart. You’re here, you grew up in the area, but you’re not that associated with the history of Rolling Stone.

I knew those guys, and they knew me. I don’t know that there was any great affection. No, my Rolling Stone history is minor.

Why was that?

I started there like everybody else. When I was in college, Ed Ward bought my first professional piece, a record review for Rolling Stone. Fifteen bucks, dude. But I was much more interested in the daily newspaper, I was much more that style of writer. I took more cues from sportswriting than the kind of underground newspaper stuff, which I thought was overly fan, and conversational, and didn’t have the kind of hard-bitten news angle that I liked. The true phrase about that was given to me by a managing editor at the Chronicle, he said, “I don’t think a sports story is worth a shit unless you know the final score by the end of the first paragraph.”

There was a point where my profile in San Francisco was enough that they were picking up on it over at Rolling Stone, and they gave me a big-deal cover assignment on the Doobie Brothers. I spent a lot of time with the Doobies in rehearsals, and put together a big long article, and they went off on tour, and the second night on tour, the lead singer quit the band, and they brought in a new lead singer, and everything had gone to hell. But the article hadn’t printed yet. I found out about this by going to Los Angeles to see the Doobies, just for fun, and who’s that? Where’s Tom Johnston? I went back and hit Rolling Stone’s office on Sunday, they pulled it off the stone, and rewrote it. And they got verb tenses wrong in the first five paragraphs. I mean, it was a mess. And I think that mess was accorded to me. They didn’t call me up for any more cover articles after that. What a funny story to come up, ha!

There are still plenty of recognizable-name rock writers here in the Bay Area, from Sylvie Simmons to Ben Fong-Torres, Michael Goldberg, Greil Marcus. I remember reading Greil early on and thinking, I’m not smart enough to understand this. He had this extra heightened intelligence that he brought to his work.

Yeah yeah, he was an academic. He developed into this incredible thing that we call Greil Marcus. He is the best Greil Marcus that you can have. Greil looks into a song, and he sees the history of the world. It’s just astonishing insights. Some of his work is better than others. But then he pops one out on Bob Dylan’s big song, “Like a Rolling Stone.” The one song. He wrote the book in six weeks. He just keeps going, tick tick tick.

So why are you so often the historical reference people call upon, for a documentary on Bay Area music history? At some point you end up being the guy.

I just hung out. I outlasted everybody, that’s all.

That’s not true.

Ha ha ha ha!

Here are some numbers. Since 2010, you have published 13 books.

That’s true. I’ve been productive in my post-newspaper life.

This is when you’re in your ’60s. Who does that?

Well, thank you Jack. Maybe I’ll get discovered after all! I keep hoping. It’s been so much fucking fun. I love writing my books, and I love writing other people’s books. I love the Ed Hardy book, that’s an amazing story about art, and culture, an independent-minded visionary. I’m really proud of that. That’s my only work outside of the music world.

Speaking of your books, you had a #1 New York Times bestseller some years ago, with Sammy Hagar. He’s lived here for a long time. but he’s not really included in SF rock history.

Not much, no. He’s meat and potatoes. He doesn’t fit the San Francisco rebel profile. And that covers a wide berth. You got Chris Isaak managing to capitalize on that maverick thing. You’ve got Metallica. But Sammy’s never gonna be that cool cat. He’s just gonna be a working-class guy. Robert Mitchum once said he figured the secret to his appeal was that people would see his face up on the screen and go, hey, that guy’s so ugly he looks like me. I think there’s something to Sammy for that.

I went into that project willingly and enthusiastically. I don’t have to like his music. But I liked his story, as I came to know Sammy and understand his story, A lot of that stuff grew on me. But a lot of it didn’t. I like Sammy’s Van Halen stuff much better than most of the Roth stuff. Except for “Jump,” which is a masterpiece. And Sammy can’t sing it.

It was your best-selling book?

Oh, no question. When I signed up the Ed Hardy book, that publisher told me they’re going to print 100,000 copies, and it was the lead item for their next catalog. So I thought, this is gonna be easy. I went to a party that night with a bunch of book people, and I was just floating around like, I’m rich and famous! It sold about 7,000 copies. Ha ha ha ha!

Befriend and betray, is the classic journalist saying. It’s your job to create an environment where they talk to you and tell their story. Of course you quote them, and that’s part of the betrayal part. You have a lot of musician friends. How do you negotiate this in your journalism?

The more you know someone, the more you’re familiar with details of their life and work, you engender sympathy. but it’s also understanding. Now I always knew why I was there. I wasn’t there because I was smart or cute or friendly. I was there because I had a job at the newspaper. and everybody knew that was what I did. I didn’t think anything about it. If something happened that I wanted to write about, I’d write about it. Then maybe have to deal with some of the repercussions.

The one that comes to mind is being in England at the Reading Festival, when Greg Kihn was kind of a big deal here in San Francisco, but just struggling to get known in England. And he just got washed out at the Reading Festival. It was awful. I filed a story from England, “Local Boy Fails” was the headline. Which is not exactly pretty. I remember Greg calling me on the phone screaming, “I told my wife everything went great!” But that’s what I was there for. I wasn’t there to be their promotion department. I was there to be the representative for the readers of the Chronicle. And that was my loyalty.

Over the years, I can imagine there have been some musicians who were dissatisfied with the Selvin coverage?

Dylan called once. He didn’t like my review of his Christian stuff. I wasn’t home, my wife at the time picked up the phone, and she thought she was talking to a drunken blues man. She was a well-raised southern girl. Ah, he’s not home. Well where is he? He’s at school. What’s he doing at school? Well, he teaches. “Well, this is Bob Dylan. And you can tell him, his license to review has been revoked.”

Wow, that sounds exactly how Bob Dylan would have worded it. Any others?

I got a phone call from John Stewart, out of the Kingston Trio, folksinger kind of guy. He had been at the Boarding House, he was sick, he had to cancel. In as a replacement, was this guy they had to fly in from Los Angeles, I’d never heard of him, named Tom Waits. And I wrote this review about how great Tom Waits was. But I couldn’t leave John Stewart alone. and I just pasted him. There was no good reason for it. He called up the next day and he said, “I love Tom, I was really glad he could do this show and he’s gonna have a fabulous career. But why did you do that to me?” I felt terrible, because he was right. It was completely gratuitous. It was just me being a smartass for no good purpose. And it informed me. It grew me up a little. You have to learn, you have to evolve.

Another good one, I reviewed The Who and the Dead, on a Saturday, and had the review in Monday. I wrote that the Dead pretty much stunk up the place. They had another show on Sunday. Tuesday morning I came into my office, and sitting on my desk—I don’t know how they got past security, or how they got to my desk—was a box of tapes. And the note on the top said, “Yeah, but you should have been there Sunday.” Somebody from the Dead circle. Tapes of the entire show, that I was not at. And they agreed that Saturday stunk, but not Sunday. That’s Grateful Dead shit.

I’ve observed that often the music from the Bay Area, the art in general, is mostly about the freedom and expression. It’s not necessarily a hub of artistic commerce, as much as it is a place for people to do whatever the hell they want. What are your thoughts on this?

The whole thing about San Francisco—it’s the final resting place of the forward march of the history of western civilization. Starting from Mesopotamia, moving west through Europe to the New World, finally in the 1840s reaching San Francisco because of a Gold Rush. So San Francisco is the final resting place of 5,000 years of forward progress, and it comes here with a bunch of zealots, madmen, and crazies that want to get rich quick. None of them do. What’s left is a community of polyglot characters that have no aristocracy, no history, no place in the land. And they have to build it really quick. So yeah, this has been a bohemian outpost since day one. Emperor Norton and all that. Robin Williams called it a human game preserve.

So true. Eventually, the internet did make a few people a bunch of money here. But the town was quite different in the ’80s and early ’90s, before the tech boom, when there were no billionaires other than the Old Money.

As AIDS sort of came to an end, that’s when the tech thing came in. And those guys came out of their offices at ten o’clock at night, hit the restaurants, and came to the clubs at midnight, and didn’t want to hear original music. They wanted to hear ironic things, like New Wave or Michael Jackson tribute bands. And just destroyed the local music scene. No offense, but they were a humorless bunch of nerds. I remember going to some mixer at one of the dot-coms, Listen.com. Surrounded by people half my age, who were telling me where they worked, and they asked me, where do you work? I said, oh, the Chronicle. And I swear to god, they didn’t know what it was.

Your favorite music book you haven’t written? Mine might be Tropical Truth, by Caetano Veloso.

The Django biography. The Howlin’ Wolf biography. And the Dino biography. Howlin’ Wolf’s is amazing, they pulled this guy out of the dark shadows of history. Django’s is astonishing. If I was Steven Spielberg, I’d be making that movie. There were four or five extraordinary scenes that would just be heart-stopping on film. Django had a nightclub in Paris. You know who reported on it for Downbeat magazine? Lieutenant Herb Caen.

That’s why I came to interview you today, Joel. That fact. My first concert was Henry Mancini. What was your first concert?

My mother took me to a children’s-only concert at Live Oak Park in Berkeley, by a blacklisted folk singer named Pete Seeger. I was about seven. But if we’re talking about a concert, I went to the Fillmore in April of ’67, to see Chuck Berry, who was just huge in my estimation, and there was a band on the bill called the Grateful Dead. That was my introduction to the hippie rock thing.

What drew you to this Jim Gordon project? People in the music industry of a certain era knew his work. But he kind of went under the radar of history. He passed away last year, and had been in prison since 1984.

He was known for one thing. And that was killing his mother. I had a conversation with an editor at a publishing house, and he said, your next book should be crime and rock and roll. As soon as he said that, Jim Gordon’s name was in my head. So I had met these women, 30 years before, who had gained Jim’s cooperation on a book. And they’d done interviews with him, they’d done some other interviews. Thirty years later, when the editor mentions this to me, I circle back and find one of these gals, and she had this stack of transcripts. So I acquired them, looked at them, and realized, I’ve got a book. This is a nut of a book. They didn’t know what they had. They had access to his storage lockers, his medical records, his diaries. I said, you have his diaries? They said, yeah, they were useless. It was just studio dates.

The diaries disappeared. The medical records disappeared. At some time during his incarceration, a con got out of the joint with power of attorney, and emptied the storage locker and stole the drum sets. They’re out there on the internet right now. All that went to hell. Only in the last ten years was his daughter able to sort of face her responsibilities to this father that she had never really been able to connect with, and put a conservatorship together.

But I had this research, and I started talking, and listening to records. and oh, man. Every record he played on, he does something special. Doesn’t matter whether it’s Merle Haggard or Gary Puckett. And something special for that record, not some little trick Jim Gordon signature. Something that is part of the composition. You see the level of this artistry, and his accomplishments.

I’ll give you an example. He went to England in a rush. He’d gotten out of the studio, and he was doing Delaney & Bonnie and Mad Dogs and Englishmen. He was on top of the world of the rock scene. And he goes to England to do a band with Eric Clapton. They do a gig, four days after he gets there, a little charity thing. They’re announced as Derek and the Dominos. The next day, they go into the studio to back up George Harrison. He’s already started his solo album, All Things Must Pass. Ringo’s been playing on it, but Ringo’s out of town for a couple weeks. And so they come in, and the first one they cut is “What is Life.” And Jim’s entrance on the drums, to that track, is so exciting, so confident, so commanding, you can feel this guy entering George Harrison’s music, reaching out and grabbing that. So he’s there for a couple weeks. And when Ringo comes back, they give Ringo a tambourine.

What are some other hits he played on?

“Rikki Don’t Lose that Number.” Steely Dan. The cross sticks came out of that Horace Silver thing. How about "Midnight at the Oasis." He dreamed up that samba beat. I’d say that’s why that was a hit record. “Layla” by Derek and the Dominos. “Sundown” by Gordon Lightfoot. “Wichita Lineman” by Glen Campbell. I love what he did on “Grazing in the Grass,” by Friends of Distinction. And I can’t get enough of “My Maria” by B.W. Stevenson.

I also see that he played on “You’re So Vain,” by Carly Simon with Mick Jagger.

Oh, the “You’re So Vain” story is awesome. They were in the studio all week trying to cut that one track. Andy Newmark took the first crack at it. And then they brought in a British session player. And Jim was going through town with Zappa. He had the night off, and just called Richard Perry, the producer. and said, hey, howya doing? And Richard said, get down here now. And Andy was there. He sat in the drum booth and watched Jim cut this thing. Five hours, 50 or so takes, not a single mistake. And at the end the snare drum was caved in like a crater. But if you ask me, that drum part is the record. The “clouds in my coffee, clouds in my coffee,” he was doing the eighth notes on the tom toms.

Jim had a way of seeing drums as a holy musical instrument. And instead of just sticking with backbeat timekeeping, he would embed his drums in the fabric of the musical composition. You can see how he prods, pokes, and moves things along. He’s got the touch that is just beyond anybody else’s abilities. As kind of a luminous inner beat that comes up after the one. There’s a whole period of time where he was a fresh face, and people would just hear him play and go, oh my god. Jack Nitzsche heard him play, and he put him to work the next day. Hal Blaine heard him play, put him to work the next day. I compare it to what [golfer] Bobby Jones said when he saw Jack Nicklaus. He said, “What game he plays, I know not.”

I’m convinced of two things and they’re really important. One is that this extraordinary, almost supernatural ability, comes from the same biochemical system that the disease comes from. And the second thing is, when Jim played drums, it shut out the disease. It put him in the world of the mighty groove, between the hypnotic effects of the rhythmic containment, and the report of the drum kit, which you feel in every part of your body. It just consumes his consciousness and eradicates the voices. And in that world, Jim was safe, he was the master of his life. And then he stopped playing drums. And it all fell apart.

So what you’re describing is in that headspace of playing music, he was in control. He wasn’t tormented. He had something to do.

It wasn’t being beleaguered by forces he couldn’t control, and tormented by doubts and pains and anxieties. This guy had as severe a case of schizophrenia as you can have, as far as the medical professionals told me. He would walk down the street, and people would walk by him, and he’d hear them say, “It’s all over. You should give it up.”

What other musicians did your research unearth, who were perhaps undiagnosed with something similar?

You think Brian Wilson heard voices? You bet he did. Peter Green, from Fleetwood Mac? Check out the lyrics to “Green Manalishi.” Skip Spence of Moby Grape. Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd. The most amazing fact that I’ve learned—schizophrenia is 1 in 100 of the population. Worldwide. Multiple sclerosis is 1 in 10,000. It’s the common cold of mental illness. They don’t know what causes it. They don’t know why it goes into remission. They don’t understand the mechanics of it. It’s this mysterious destructive force in people’s lives. Vast numbers of people sleeping under freeways in the cold, in the wet, with voices buzzing in their heads.

What is the most current treatment for schizophrenia?

They don’t have much treatment. Jim was subjected to horrible, primitive, sledgehammer type things. He was on Haldol, which gives you a constrictive feeling in your ribs. He was playing drums wearing a chemical straitjacket. He was on massive tranquilizers, heavy duty anti-psychotics, and plenty of alcohol and cocaine, which was more effective for him, actually.

All your books have a narrative arc, but this one is really something special. You have told me that this book affected you more than the others.

I came to care for Jim. Immediately I was aware that he had not been the beneficiary of any compassion or understanding. Nobody knew about the five years before he killed his mother, of the tortured hellscape he lived in. It just happened, and everybody just turned out the lights. They turned their backs on him. Nobody came to the trial, nobody came to the jail. It was just, forget about him.

So the whole thing of who Jim Gordon was, has just been rolled up into this crime. And I started to see how much struggle, how shamed he was of it. The incredible lengths to try and cover it up and manage it. The explosions of uncontrollable behavior that betrayed his best efforts to be a normal, decent human being. And when I realized how little support he had, and how little connections were out there, how alone he was, how he suffered by himself like this, I just couldn’t help but feel tremendously for this guy.

I’ve really got my heart into this. I’m on this mission. I want Jim to be restored to his place in music. He’s number 59 on the Rolling Stone list of greatest drummers. 58 is Sheila E.

So let’s play the Joel Selvin Lightning Round. Give me one word or one sentence about each of these Bay Area musical artists. From the eras you’ve covered. You’ve reviewed or met most of these people. Just say the first thing that comes to your mind.

Dave Brubeck

I lived across the street from him in the ’70s in the Oakland hills.

Kingston Trio

Whoah. Bob Shane.

Grateful Dead

I love the Dead, they’re an exercise in, they call it diving for pearls. I’ve had some of the best musical moments in my life to the Grateful Dead, and I’ve had some of the longest, more boring stretches at the same time.

Jefferson Airplane

They were the kings and queen of the scene. They ruled, their reign was glorious.

It’s a Beautiful Day

I loved those guys! They were a favorite of mine. Pattie Santos, oh my god, she made my heart weak as a teenager. They had a really great light show that went with it, really made that thing flash at the Fillmore.

Count Five

That guy’s name is Kenn Ellner, he was a music business attorney from San Jose. So I’m at the Bohemian Club, and Steve Miller is chumming up with Greg Kihn, who is sitting, glowing with attention from the rock star, and I said, “Steve, you want to meet the guy from Count Five?” And Greg Kihn was instantly forgotten.

Dino Valenti

Valenti was a very complicated, difficult, and ultimately, it turned out, mentally ill person who had a tumor. I worked on doing some pre-production work on a documentary about him.

Dan Hicks

Dan Hicks came over here to do a radio show with me, and he brought a bunch of tapes. And one of the things he brought was the Muzak version of “I Scare Myself.”

Beau Brummels

Those guys were the greatest. Sal Valentino is one of the most underrated vocalists in the history of rock. He’s like a Van Morrison kind of figure. I asked Sal once, what was the most money he ever made in the record business, and he told me he got $5,000 from Warner Brothers for bringing Rickie Lee Jones to the label.

Hot Tuna

There are trees that grew up during Hot Tuna performances.

Marty Balin solo

So Marty is like the James Dean of San Francisco rock. Always had a chip on his shoulder, and a song in his heart. He was a fantastic figure.

Blue Cheer

Loudest San Francisco band of the day. I remember seeing them in the Palace of Fine Arts, before it had been restored, and they made the walls shake.

Santana

The early Santana, probably the best band out of San Francisco.

Steve Miller

My daughter’s godfather. I saw the Steve Miller Blues Band before they ever played the Fillmore, I just think he’s one of the greats of classic rock music.

Flamin’ Groovies

Wonderful band. Roy Loney. Cyril Jordan, still holding up, wow.

Malo

Oh! Great song [“Suavecito”]. Arcelio Garcia was a very important figure in the Latin rock community.

Earth Quake

I loved Earth Quake, they were Berkeley’s Rolling Stones.

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Spent a lot of time in 1969 and 1970 writing teeny-bop magazine articles about Creedence, ’cause they were the biggest thing in the world. So I got to know all those guys. I was there while they recorded Pendulum, and John Fogerty’s one of the most tightly wrapped individuals I’ve ever met. They were doing all this huge massive publicity behind the Pendulum release, and I asked him why, and he said, “’Cause I want John, Tom, Stu, and Doug to roll off people’s lips like John, Paul, George, and Ringo.”

Sopwith Camel

Peter Kraemer comes from real beatnik aristocracy. Black Sun Press, his mother was in with that crowd, and he was brought up super bohemian. He lived on a houseboat in Sausalito. The whole Sopwith Camel, that was just sort of a wrinkle that could only happen in San Francisco in ’65.

Lydia Pence and Cold Blood

That was the first real blast of hot soul, they showed up about the same time as Tower of Power did. By 1969-1970 the whole Stax Volt thing had emerged, and this was sort of the San Francisco answer to that.

Chris Isaak

Loved Isaak from day one. It’s like cool rockabilly, little bits of Orbison, little bits of Elvis, little bits of New Wave rock.

Eddie Money

Eddie Mahoney. Oh man, we had a lot of history. Eddie willed himself into rock stardom.

The Tubes

My favorite band of that era. They were just the most creative, wild, and imaginative. Their shows were super dense, multimedia.

Tower of Power

Fantastic band. Emilio Castillo and Stephen “Doc” Kupka. You just can’t say enough about those guys. And also Rocco and Garibaldi, that rhythm section is classic, up there with Muscle Shoals and Stax Volt.

The Nuns

I had been to London and watched crowds gob the bands, been to the men’s room at CBGB’s. And consequently, SF punk seemed a tad playhouse to me. But I remember running into producer David Rubinson in the halls of the Automatt and noting he had been in the studio with The Nuns. He said yes. I said, “David, they aren’t even competent on their instruments.” He said, “You have to get into the space where competence is no longer relevant.” He had drunk the kool-aid.

The Avengers

Wilsey and Penelope had something going.

Dead Kennedys

Dug Jello, the band could be rough. Loved the Deaf Club.

SVT

Oh! “Heart of Stone,” one of the best records of 1979. Then they re-recorded it and lost it. But that original single, on 415 Records, that was just a bullet to the heart. Jack Casady, Brian Marnell, Paul Zahl, Nick Buck, I can’t believe I remember these names.

Night Ranger

Aww, man. You know…B-grade Sammy Hagar stuff. I saw those guys at a rock festival up at Calaveras County, and Jack Blades pissed off the audience, he said, “Hey, we just got back from Europe. You know where Europe is, don’t you?” I mentioned that to Jack, and he said, “Yeah, I guess I was talking down a little.”

Sylvester

An absolute buried treasure. I remember talking to his manager, who had been with him forever, and saying, “You’re like the little house on the corner, you just need a fresh coat of paint, and everybody’s gonna say, ’Oh, has that always been there?’”

Romeo Void

Deborah Iyall, one of the most creative and expressive individuals I’ve ever seen. She was a raw nerve. I loved Deborah.

The Rubinoos

Aren’t they cute as hell? I saw one of their first gigs, when they were 14, and they were the band of the younger brother of Earth Quake’s lead guitarist. They were like little puppies. I saw them 50 years later, and they’re still little puppies. They’re amazing.

Huey Lewis and the News

Huey, great guy. Love that band. They were a San Francisco bar band that managed to capitalize on that. Huey told me, “We’re a San Francisco band, we found the five closest musicians and started playing.”

Clover

Elvis Costello’s first record. He’s never made a better one. It’s Huey’s band. Huey went to Amsterdam to smoke pot and get laid that weekend, so he’s not on the sessions. They were this legendary San Francisco band that struck out here so bad, their last chance was to try England. And they all got new clothes and started hanging out with Dave Edmunds. It worked out okay for a little bit, they got a couple albums out over there. But they came back and broke up, and started doing these jam sessions in Corte Madera, and that’s where Huey picked them up.

Journey

Oh yeah, well, I was there at the beginning, I was there at the end. And it was a big story for the Chronicle all along. It was interesting to follow. I loved Herbie Herbert, their manager and chief tactician. The band never really moved me. But it was certainly fascinating to watch the military-industrial complex of rock.

Pablo Cruise

That was sort of the beginning of the bland San Francisco ’70s commercial sound. They came out of a hippie rock band called Stoneground, it was almost a communal affair that Sal Valentino had been involved in. A couple of the guys decided to be a little more strategic about their music, and that’s what they came up with. They beat Elvis’ record of attendance at Caesars Tahoe.

Pointer Sisters

I saw them first as background singers, at Keystone Corner, in the Elvin Bishop Band. They were really smart, good, funny gals, and like you can imagine, they didn’t get along.

Third Eye Blind

That guy was hilarious. I did a massive article on him, based on him ripping off so many other people, and shitting all over the place. I collected all that information, and then talked to him. And we spent five hours, and he was fantastic. He deflected everything he said. I remember I said, somebody complained that when they played at the Paradise he acted like he had an audience of 10,000, and he said, “You should see me at rehearsal.”

4 Non Blondes

Linda Perry had “I want this all” tattooed on her fingers. She was intense.

Tracy Chapman

Never ran across her.

Robert Cray

Cray’s band came out of a Berkeley nightclub called the Rathskeller. They were this blues band of all blues bands. That’s where his breakthrough came, right out of the basement of the Rathskeller on Telegraph Avenue.

Tom Waits

I refer you to the podcast that Tom and I did in this basement. I love Tom. We once did an interesting interview at some Chinese restaurant in the Mission. He was prepared for it, brought notes. He’s a one-of-a-kind personality, and his music is spectacular. Go to the podcast, he brought a bunch of records from his collection. He didn’t want to play his records. He wanted to play Pete Seeger and William Burroughs,

Joe Satriani

I asked him once if he practices guitar as much as eight hours a day, and he said, yeah, about eight hours. and his wife was standing there going, [shaking her head]. Ha ha ha ha ha!

Primus

Primus sucks, right?

Eric Martin

Sweet guy, really sweet guy. And so desirous of his success that he finally achieved it in Japan. And has one of the worst number-one records in the history of rock.

Greg Kihn

Greg turned into the Archie Bunker of rock on the airwaves.

Sheila E.

Hot gal, can play timbales, and obviously had Prince’s attention for a hot period of time. But she is not number 58 on the chart above Jim Gordon!

The Call

Oh, Michael Been, he was something, wasn’t he? Didn’t Al Gore use his thing for a campaign song? His wife was a Unitarian minister. All his songs were these strongly spiritual things. And then he died young, having mentored his kid in the Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. Michael was an amazing guy.

Windham Hill Records

Will Ackerman brought me his first record, I thought he was nuts. And then this music started getting played everywhere I went. And I realized that he stumbled onto something that nobody else understood. And George Winston was this huge hit, he found some sort of space for music that really resonated with people. And then George turned out to be the greatest guy, who loved New Orleans piano players, and was responsible for bringing Henry Butler out.

John Lee Hooker

Well, John Lee was this sort of éminence grise of the blues scene in his later years. He’d come and sit in a jam, and his jam was always the same.

The Motels

I was just hanging out with Jeff Jourard of The Motels, he was also in Tom Petty’s band in the early days. Martha Davis and I were in elementary school together. She was a year behind me, her sister Janet was in my class. She moved from Berkeley to L.A., and that’s where she put The Motels together, and now she’s up in Oregon.

Metallica

Oh you know, those guys, I have begrudging admiration without liking the music. They have a very strict sense of what their music is, and they stayed with it. The thing about Metallica, go to used record stores and try to find Metallica records. They don’t exist. And it’s not because they didn’t print millions of them. It’s because everybody who has them, kept them.

Faith No More

That was a wonderful moment. “We Care a Lot.”

Red House Painters

Mark Kozalek wrote a song about my favorite restaurant and how it failed. And it captures the whole thing, about this wonderful restaurant that went to hell. It was down near the baseball park. Beautiful little outdoor restaurant, had a bar. Mission Rock Resort. They had a fire, and they just never brought the heart back to it.

Green Day

I ran into those guys right when they put out Dookie, and they were so young that when I was interviewing them they kept calling me “Mr. Selvin.” They were the real deal, I knew that right away. Very smart, all three of them. They did something really great. And I saw them do the baseball park and they were fucking wonderful. Good heart, it’s upbeat, it’s positive, it’s in the community.

Charlie Hunter

Fantastic. I first heard Charlie Hunter in Les Claypool’s living room. He was playing a strange number of strings, and he had these fantastic tunings. This was just before he moved to New York and blew them all out there. Les was the first guy to find him.

Michael Franti

Franti’s such a character. The barefoot thing, and the yoga stuff. He’s something special. That’s San Francisco shit.

Chuck Prophet

Love Chuck, what a great guy. And he’s got the spirit. Temple Beautiful is the shit.

Mother Hips

Yeah! Those guys had a sort of funny moment where jam band and pop-rock came together. They were from Chico, or somewhere outward. They had a huge following.

Jackie Greene

Love Jackie. He’s like the younger brother to all these guys. And I really loved his first three albums, and counseled him against joining Phil Lesh. I said, you’ll be playing to Deadheads the rest of your life. You’ll never be recognized for your songwriting. He was kind of aware of that, but he didn’t have any dough, he was living in his car. Phil Lesh had some real bucks for him.

Train

I don’t get that guy. Other people do.

Joel, thank you so much!

Oh man, it was great.

Absolutely fabulous interview Jack! Howdy Joel - thanks for the skinny on everybody. I looked for it online, but I could not find the John Wasserman review of Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Do you know where to find it? Also great litany of SF players. They might've been a little bit after your active reviewing career, but what do you think of Brian Jonestown Massacre?

i believe Selvin’s pop was also in papers, so, nepotism, yeah.