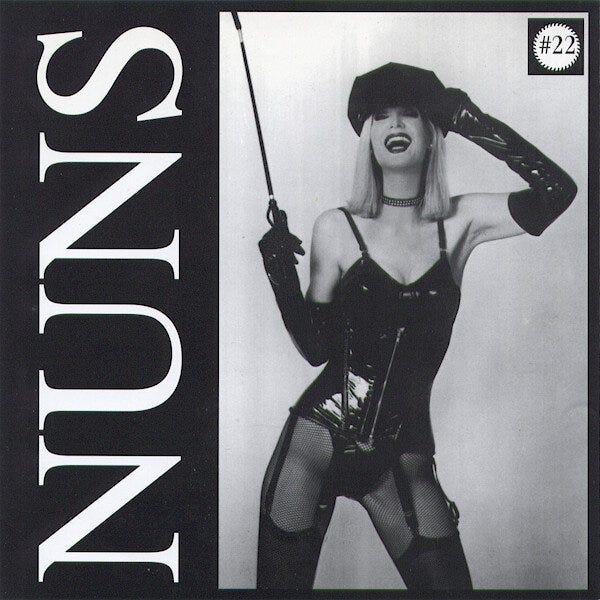

Jennifer Miro of The Nuns

The band's keyboardist/vocalist was enigmatic and mysterious to the end

The Nuns members Alejandro Escovedo, Jennifer Miro, Jeff Olener

Thanks for reading, and welcome to all of you new subscribers. I did a reading last weekend at Spec’s bar in San Francisco’s North Beach, and afterwards it was delightful to meet Nora Murphy, who hosts the weekly punk/post-punk radio show “Left of the Dial” on KSVY in Sonoma. She bought one of my books, and our conversation reminded me of this story. I’ve been meaning to share it on Substack, so here it is.

After Jennifer Miro passed away in 2011, I got an email from critic and author Ian S. Port, who was the SF Weekly music editor at the time. He asked if I could write up something about her. The Nuns were part of the first wave of Bay Area punk, and Silke Tudor and I had included her voice in our 2009 punk oral history, Gimme Something Better. I dug up her transcript and some notes I took at the time, and fashioned this essay. It first appeared in SF Weekly in early 2012.

If we’re talking the birth of Bay Area punk, there are as many points of view as there were people in the clubs. This timeline is the one generally agreed upon: The city’s first true punk club show—The Ramones, Savoy Tivoli upstairs, August 1976. The first local punk act—former stripper Mary Monday, with her band the Bitches. The first punk single—“Hot Wire My Heart” by Crime, 1976. The first band to play Mabuhay Gardens—The Nuns, December 1976.

Punks don’t necessarily have a long lifespan. Nearly all the Ramones are gone. Mary Monday moved to Alaska and died. Three members of Crime are dead. And last month, one of the scene’s founding females, Nuns keyboardist Jennifer “Miro” Anderson, passed away from cancer in New York. She had been playing in a version of The Nuns more or less continuously since the age of 18.

Despite devoting her entire adult life to making music, Jennifer never achieved much success or notoriety. Few from the Bay Area punk scene had any idea of her whereabouts. She had no steady boyfriend, no children, no connection with her family back in California. But enigmatic and mysterious, and still gorgeous, to the end? Absolutely.

When Silke Tudor and I were assembling our Gimme Something Better oral history, we set out to interview the first wave of Bay Area punk. Members of Crime, The Avengers, Negative Trend, Flipper, The Mutants, Dead Kennedys, and many others agreed to speak with us. But The Nuns were another story.

In the mid-70s, as the radio played dreck like Bee Gees and Peter Frampton and Barry Manilow, Bay Area kids were flocking to North Beach to see something chaotic and wild. Punk had not yet been codified. There was no dress code, no tats across the stomach, no Hot Topic stores, no guitars covered in stickers. Nobody had yet popularized the phrase, “Dude, that’s so punk rock.”

San Francisco’s first homegrown punk rock stars were Crime and The Nuns. Crime quickly developed a well-coiffed deadpan performance shtick, four guys wearing police uniforms, zoot suits, or candy-striper dresses. The Nuns were very different. They appeared to throw everything against the wall to see what stuck, from quiet Weimar piano ditties to what later might be called New Wave pop, to fast and raunchy New York-style rock and roll.

Most bands are led by a single identifiable personality, standing front and center, anchoring the stage. The Nuns had three lead vocalists—platinum-blonde teenage Jennifer, gravely-voiced gay New Yorker Richie Detrick, and band co-founder Jeff Olener, who would pop out his false teeth as a gross-out gag.

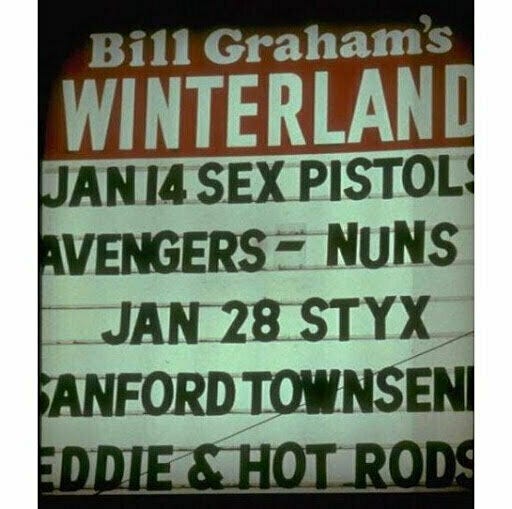

The Nuns and Crime both drew lines around the block at the Mabuhay, but The Nuns stood out thanks to mysterious investors, and a management team that would later include Bill Graham. Other bands in the scene watched helplessly as high-priced Nuns billboards and radio ads bombarded the city. Big-ticket shows like Bryan Ferry and The Ramones and The Dictators and Television and The Damned all featured The Nuns as opening act. Nuns members partied with David Bowie and Iggy Pop and Sid Vicious. They had meetings with Sire Records in Los Angeles, and played the infamous final Sex Pistols show at Winterland.

They sang songs about suicide, fat chicks, decadent Jews, child molesters, and World War III. It was a fabulous mess, sloppy and out of tune, but at least it wasn’t the same old dinosaur rock like Steve fucking Miller. And like all the early S.F. punk bands, things ended abruptly, in a pile of drugs, finger-pointing, and bitterness.

The Nuns did not want to talk to us. Guitarist Alejandro Escovedo, now a respected solo artist in Texas, begged no interview. Bassist Mike Varney, founder and proprietor of Novato’s Shrapnel Records metal label, didn’t answer messages. Jeff Olener, who had started the band with Escovedo as a class project at College of Marin, hung up the phone. It seemed like a bad dream everyone was hoping to forget.

Finally, in 2008 the onetime Nuns manager Edwin Heaven put us in touch with Jennifer, who graciously agreed to chat with me in New York. I had no idea what to expect. I knew she had worked as a fetish model, under the name “Mistress Jennifer.” She kept The Nuns going throughout the 2000s, but the videos bore zero resemblance to the Mabuhay era. Clips of half-naked vampire girls gyrating to Goth synth-rock seemed light-years away from the arty North Beach origins.

I walked into a tea shop with tablecloths on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, looking for a surgically enhanced blonde woman in black leather lingerie, smacking a riding crop. Instead, Jennifer was sitting by herself, wearing conservative clothing more appropriate for a law office, which is where she worked. She ordered pots of tea and a plate of scones for us to share, and seemed to enjoy reminiscing about her punk past. I had seen the late-70s photos of her, taken by Mab scene photographers like James Stark and Chester Simpson. The beautiful porcelain-skin blonde, calculated and cold, smirking and wearing something couture, hyper-aware of her posture. She seemed to still be all that, but I also found her very warm and articulate, with an unexpected streak of humility.

“I grew up in Mill Valley, California and I think all my rebellious things started with men,” she began. “I had a lot of anger towards men, because I was suddenly a teenage girl and I was sexy. Even my high school teacher was coming on to me, and would grab me, and he was always having sex with his students. He ended up marrying one of our students. It was kind of disgusting.

“In the early seventies, I was a little monster. When I was 16, I had three different coke dealer boyfriends that would pick me up at high school in leather-upholstered Jaguars. I would wear furs and makeup to school, and everybody hated me. I was a total snob. I would never date an actual high school boy. I had my rich boyfriends, they were all classy guys. The really scary thing is, I’m dating the same type of guy, but they’re not coke dealers, unfortunately. I think it would be better if I was dating coke dealers. Anyway, so I grew up really fast, obviously.”

She studied classical piano, but quickly gravitated to the mid-70s glam scene, hanging out with bands like the New York Dolls at Rodney Bingenheimer’s club in Los Angeles. People magazine ran a photo of her at age 16, at the release party for David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel.” When the Ramones played the Savoy shows in North Beach, Jennifer was right there in the audience, along with a cluster of hipsters who would later form the bands Crime, The Nuns, and The Avengers.

People remembered her as aloof and withdrawn, sitting backstage by herself, reading a book before a show. I began to realize that more than anything else, she was just an insecure rich-girl teenager who craved the spotlight and wasn’t prepared to handle the attention.

“I was really snooty. But I really wasn’t that confident in those days. I had all these guys coming on to me because I was really young and I was unattached. It was kind of weird. There were all these rock stars wanting to date me and all these people, so I just kind of closed off.”

Photo by James Stark

I asked what it might have been like as a female in such a male-dominated scene. Did she form bonds with other girls?

“No, they all hated me,” she replied. “Penelope [Houston, from The Avengers] and I sort of knew each other, but we never really bonded because I was so different from those girls. They were all kind of rough, tough sleazy street girls, and I was elegant, and wearing black evening gowns and perfect makeup and they all hated me, because I was this posh lady. But you know, people in bands all hate each other. Bands hate other bands. Even to this day, I’m not that big and I’m not that famous, but I still have a lot of problems, especially since I’m still dating people in show business, and bands and clubs. So I still get that kind of competitive jealousy, even on the smallest level.”

The Nuns imploded for the usual reasons—cocaine and heroin and booze, strong competing personalities, a music industry that didn’t want to take the risk. According to Jennifer, it didn’t help that the band was managed by drug dealers.

“The whole thing, it’s like a building with a decaying foundation—when the foundation of your building is made of drugs, you know. What’s gonna happen? Gee, I wonder!” She laughed out loud, and a few old ladies looked up from a nearby table.

“So obviously the whole thing sort of deteriorated. Alejandro formed his other band Rank and File, and then we went back to New York and I tried to plead with the drug dealer managers, I said, ‘Well what are we gonna do? Since everyone’s doing drugs, don’t you think maybe we should try and pull this thing together and get straight?” And they go, ‘Well, why don’t you quit?’ That’s what they said to me. That was their solution. Apparently they had some tax evasion problems, so they ended up in South America, and they’re still there. It was a bit of a money laundering thing, oh yes.”

The Nuns’ songs were eventually recorded on an album, and versions of the band continued intermittently throughout the years, but even though she was now the group’s most recognizable face, she seemed less inclined to talk about that history. I asked her how the other members of the original Nuns viewed the direction she took.

“They all kind of sneer at The Nuns,” she said. “They look at The Nuns as a joke. To me The Nuns were really a cool band. We never sold out, we never made it big, we never became a big commercial thing. But so what? A lot of people don’t make it in showbiz. I’ve been basically in and around showbiz people since then, and none of them make it either, so it’s not just us. Showbiz is very, very cutthroat, very competitive. The weird thing is, I keep thinking it’s going to end. But I’m still doing The Nuns. I’m still doing it.”

I asked her what she took away from the whole experience, and she burst out laughing. “Don’t ever, ever get into a band! Do something else with your life. Be a lawyer, be a waitress—anything. I would have been much better off if I had just gone to Vassar and married some investment banker.”

As noted in her obituaries, including the San Francisco Chronicle, Jennifer passed away with no family or friends around her, other than a neighbor who doubled as caregiver. She left an apartment filled with Nuns photos, flyers, and recordings. But rather than remember her as clinging to clippings like a punk-rock Norma Desmond, we can also watch archival clips that reveal her, and The Nuns, in their prime.

On January 14, 1978, at the Winterland in San Francisco, what would be the final show ever for the Sex Pistols, the most talked-about punk show in history, before the mob of 5,000 roared to life and pelted the stage with spit and D-sized batteries, before anyone knew what to expect, before rock media anointed this night as the death of punk rock, before the voiceover introduction, “We’re The Nuns, and we ain’t from New York, and we ain’t from England, we’re from San Francisco!”, the very first person to take the stage was Jennifer, walking out by herself in a single spotlight, scared to death and emotionally fragile from just having broken up with Crime drummer Brittley Black. She sat at her piano, began a closing-time saloon melody, leaned into the mic and sang, “I’m so lazy, so lazy…I’m too lazy to fall in love…It’s such a bother, I’d much rather stay home and watch TV...”

Jennifer remembered the moment clearly. “After that,” she said, “you can’t go back to a normal life.”

Another great piece of San Francisco history. You make it so vivid, even though I was only 9 years old and living in Houston, Texas at the time, I feel like I could've been there. When I eventually made it to San Francisco, everyone was always declaring "the scene" dead, but it seemed to go on regardless of any such claims, always shifting a little into something slightly else, but still a place to get and stay weird. I don't know how true that is now, because who can afford to be weird there anymore, but I hope it always retains some of that magic.

I'll be spending the rest of my day trying to square the words "The Ramones" with "Savoy Tivoli" in my head. I just see every single wineglass in that place exploding.