Jeneé Darden: Beyoncé, Black Country, and the Positivity of Journalism

A conversation about music, writing, and the late, lamented Oakland Book Festival

Jeneé Darden is an award-winning journalist, author, public speaker, mental health advocate, and host of the weekly Sights & Sounds program on KALW in the Bay Area. She has interviewed and/or produced interviews with a slew of newsmakers and entertainers, from Alice Walker to Iyanla Vanzant, Eric Jerome Dickey, Mary Monroe, comedian Luenell, Adam Savage, filmmaker Malcolm Spellman, Edward James Olmos, Benjamin Bratt, cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz, Erika Alexander, U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, Kelly Rowland, Common, Fantastic Negrito, Van Jones, and everyday people making a difference in the world. She also hosts readings at Books, Inc., and at the new KALW station space on Montgomery Street in San Francisco. And she lives in Oakland. We’ve known each other for some years, and I love what she does, and what she’s putting out there, and so let’s just jump in.

We’re talking on the eve of release of the Beyoncé Cowboy Carter country album.

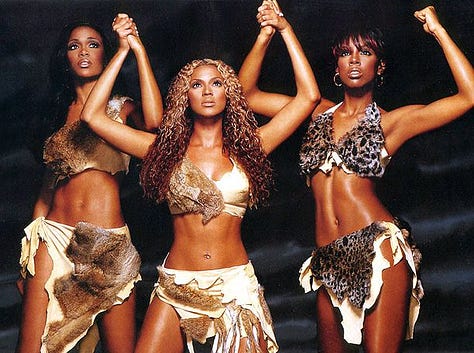

It’ll be interesting to see what influence this is going to have on the industry. I remember when Destiny’s Child came out, and I was young, maybe my late teens. I just remember how big of a deal they were. And at that time, for a lot of people, it wasn’t like Beyoncé was the standout, and they were the backup. It was like, we all kind of liked each one. Some people had their favorites. And it wasn’t just Beyoncé.

And the way they were marketed, these insane photo shoots.

They were in a lot of Black media, before they even went mainstream. They were everywhere, Vibe and BET, they were huge. So when I used to work at NPR for the West Coast Bureau, I had produced the interview with her father, Mathew Knowles. This was when it was rumored her and Jay-Z were together, but it hadn’t been confirmed.

He was the manager for both Destiny’s Child and then the Beyoncé solo career, and then she fired him, for allegedly stealing from her. Is he like Serena Williams’ dad? Was he that kind of crazy?

I didn’t get that vibe from him. As far as I remember, Beyonce has said her dad was crazy. She meant like, as far as how he handled business, and his aggression. I could tell, he was just very strategic. Very strategic.

So now she’s releasing this new album, with guest stars like Willie Nelson and Dolly Parton.

I was hoping she would do a country album because I loved her song “Daddy Lessons” from Lemonade. So I was excited. What she’s doing is, she’s doing genres of music that Black people either started or were pivotal in starting. So the first album was house, this was country. And so people are speculating the third one of the Renaissance trilogy will be rock and roll.

She’s doing a rock album next?

That's what some people are speculating. And she did some rock music on Lemonade. So she’s doing genres where Black people have been erased, even though we either started them or were very instrumental.

I mean, Big Mama Thornton, “You ain’t nothing but a hound dog.” She was the first to record it. So many people still think Elvis was the first version, you know?

Yeah. Yeah.

And who was that lady who played electric guitar? Rosetta?

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, right.

Oh, my god. There’s video of her on YouTube. She was just phenomenal. Why is she not in every Hall of Fame?

Yeah. Yeah. That’s what I’m saying. There’s so many. So I hope it makes the country music industry more open to having different types of artists.

This Beyoncé record is going be a huge, huge deal. She’s one of the bestselling music artists in the world.

I mean, she did it ’cause she was treated terribly, in part, at the Country Music Awards.

Right. That’s a very famous episode, at the 2016 Awards, when Beyoncé appeared onstage with The Chicks, and although the venue audience was on its feet, the online backlash was brutal. Some country fans were enraged, posting nasty racist comments, and Beyoncé fans countered, accusing the CMA of deleting promotional posts about the performance.

So I grew up with country music. I don’t know why it is still so rigid and stratified like that. I just don’t get it. I mean, every family has parts of them that is rural and poor, with breakups, heartache, pickup trucks, trains, prison, whiskey, you know. You’d think it would be more universal, right?

Yeah, we’ll see. I think the expectations of country music aren’t gonna change, at least for another generation.

So I just recently saw an article about this Black country artist from Oakland named Miko Marks. Do you know her?

Oh, yes. Yes. I’ve interviewed Miko.

Tell me what she’s like. The headline was something about, roller-skating country artist from Oakland.

She’s from Flint, Michigan, I believe. And she’s been in Oakland for a while. And yeah, she roller-skates! She roller-skates around the lake. She’s an incredible singer. Miko Marks has the most amazing voice. I saw her perform at Freight & Salvage for Black Opry, which is a Black country organization where they set up shows around the country, with Black artists. And she just blew us all away.

I remember when I first saw her in the early 2000s. She was coming up, and there was a lot of buzz about her to be the next big country star. And it didn’t happen because the music industry was trying to define her, and they wouldn’t let her be the star that she wanted. So she quit country for awhile. And she came back. It was really a pleasure to talk to her and to hear her sing. I really recommend people go hear her live.

Yeah, I stumbled upon her recently and she just released a new remix with the musician Buddy Miller. He’s sort of like a support band and curator for all of the cool acts at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass. He brought Yola to HSB a few years back.

Oh, that’s awesome.

The whole thing about the country music world, if people go back and research, there’s a long history of Black artists in country music.

Yeah, I went to see the Black Opry Revue, they came to Freight & Salvage, they’ve been coming a few times a year. When I was listening to them sing, you can hear the gospel and the blues, you could hear all of that in their music. So you could see how country has such deep roots in Black culture. I was like, oh, I hear it now, you know.

I love that performance at the Grammys with Tracy Chapman, and what’s his name, Luke Combs? I was watching it the other night. I’ve watched it so many times. That was such a beautiful performance.

So you grew up in Oakland, I’m guessing the 1980s was your childhood?

Yes, very much so. ’80s and ’90s.

So what was it like for you back then? You were living with your mom. Do you have any siblings?

My father has other children in Southern California, but I didn’t grow up with them. I’m like, 20 years older than them. I grew up as an only child, because my father started having more children after I went to college.

I grew up in East Oakland specifically. For the most part, I think I had a good childhood. I mean, of course it had its challenges, but my grandparents were from Mississippi and Texas. Sometimes people think I have a Southern accent, the way I say things, but that’s ’cause I grew up around them, and they took care of me when my mother went to work. So I had this influence of California culture, Bay Area culture, and Black Southern Mississippi and Texas.

The South, with that accent. My dad and my grandmother were from Texas. I grew up with that in my house. It never goes away.

It doesn’t, it doesn’t go away. And it’s special. And when they migrated here, they all lived within a mile radius. So it was all these family members that were just so close. Good dinners, good dinners. Some of the best food. Mm hmm.

So what made you decide, I’m gonna go to southern California to go to college? I’m out, I’m getting out.

I wanted to try and live somewhere else. I always wanted to go away for college. I applied to different schools. My grandmother lived by Mills College, and she wanted me to go to Mills College. She was like, let’s go to school there. And I was like, that’s really too close to home.

Yeah, you don’t want to go to college and then come home for lunch, you know?

Exactly.

So was that a shock to move to southern California?

I went to U.C. San Diego, which is in La Jolla. And at the time, it probably still is today, La Jolla was one of the wealthiest cities in the country. It’s very, very, very suburban. So it was definitely a culture shock to come from growing up in Oakland, hanging out in Berkeley and San Francisco, to go to this very suburban, wealthy, quiet place.

Right, right. And let’s say Caucasian, pretty Caucasian.

Yeah, it wasn’t very diverse either. I don't know if it’s changed, but La Jolla wasn't very open to students. There wasn’t anything going on off-campus. We’d have to go to San Diego to do fun things. And it wasn’t just the students of color that complained, it was all the students. It’s like, all we're doing is studying.

So did you know that you wanted to be in broadcasting? Were you already doing that as an undergrad?

When I was an undergrad, this was before podcasts, iPods, all that kind of stuff. I wanted to go into magazines and newspapers. So I interned at an interior decorating magazine. And then after I graduated college, I moved back home to Oakland. I was working as a TA, ’cause I was still kind of like, let me just make sure I definitely wanna go into journalism. I was writing for small local publications here. And I was like, I don’t wanna do this. But I don’t wanna be on TV.

So I moved back to Southern California, and I went to journalism school at USC. USC was preparing us to be multimedia journalists. We would have to take classes in broadcast, print and online reporting. I started getting interested in radio. And so I took a radio class, and then that was it.

Let’s talk about what you do at KALW. You showcase a very wide palette of people in your interviews. So the story ideas are not assigned, they’re your ideas?

Yes, so it’s me and my producer, Porfirio Rangel. We have meetings every week and we talk about people who we want to interview, who are artists. I like to be as broad as possible because if not, it would sound like the hip-hop jazz poetry show.

We like to have a huge range because that’s the Bay Area, so many people doing so many things. The Bay Area is so influential in pop culture, nationally and globally. So much starts here, that goes out to the world and pushes the needle in pop culture.

Why do you think that is? Why do you think we have this outsized reputation as a creativity incubator?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I think part of it is because so many people move here from other parts of the country and the world. So you get all these different influences mixed in with the Bay Area culture. I think the Bay Area is this place where you’re allowed more to be yourself. And so you can really just go with the creativity.

Yeah, I always felt that too. It isn’t like New York or Los Angeles where they’re like, you better be pro, you better roll in hot, and you better have it all together or we’re not gonna pay attention to you.

Right, you’re not thinking about what the studios are thinking or the music industry is thinking. Here, it’s grassroots creativity.

Many people move to the Bay Area because they’ll be more accepted with their sexualities. Some people move here because of the activism here. I have a friend who’s a minister. That’s why he moved here, because he thought the faith community was more progressive, than maybe the other parts of the country.

I just interviewed somebody who’s doing an exhibit on the Great Migration. You know, six million Black people migrated out of the South. And a lot of them came to California. My grandparents came to California. Coming here for a better opportunity, right? And to be themselves and to have more rights and privileges.

So when your grandparents came out during the Great Migration, some of that was during World War II? The war effort, building up the boats and ships and stuff?

You’re dead on. There were different waves of it. And definitely, that’s my grandparents. My grandfather worked on the shipyards in Richmond. And then my other grandfather was a longshoreman. So definitely, yeah, that all played a part.

So, you’ve written poetry. You’ve written essays, published a book, and contributed to anthologies. How does your brain sort out the idea of being a journalist and interviewing people and getting their stories, versus you sitting in a corner and writing your own stories by yourself? Because it’s a polar opposite writing style, when you think about it.

Oh, it is. No, it totally is. I mean, even like writing for broadcast versus writing a magazine article or an essay. I feel like it’s a dial, and I have to switch my brain into the writing style. And I’ve been journaling since I was seven. So for me, it’s therapeutic to journal and to write about myself. I know how to go into that space and write about my own experiences. And then also, I know how to ask people questions, and get in their business.

Was there one story where you suddenly realized, oh my god, I’m a real journalist? I’ve certainly experienced this myself. Was there a moment when you were working on a story and you’re like, this is out of my league, but I think it’s helpful for me to continue?

Yeah. It was 2005. I was in journalism school and I had an internship at Time magazine in London. I was there for the summer and that was my first time off the continent of North America. Towards the end of the internship, maybe two or three days before we were supposed to come back to the U.S., Al-Qaeda bombed the city. It was the largest terrorist attack in the history of London.

And this was the transit bombings. I remember that.

It’s interesting because usually I would take the train to Time magazine, and that morning, my alarm didn't go off. And I was like, oh man, I’m gonna have to take the bus. And I’m glad I did, because they bombed King Cross station, and I had to go through King Cross to get to Time magazine. So I might’ve been on one of those trains.

When I got to work, I didn’t know what was going on. I don’t think anybody knew anything that was happening. Everybody looked frenzied. And they were like, everybody has to go out and cover this. Even you. And I was the intern. So me and another reporter, she was Egyptian, we went to Muslim neighborhoods in London to talk to how people were feeling. And people were scared, because they thought they were getting deported. They thought there was going to be anti-Muslim backlash. We talked to people who were refugees, and they were like, we came here to get away from that. We went to hospitals, to get counts of people that had perished. No buses or anything were running. So, of course, I picked the day to wear tall leather boots.

So you were stomping all around London in boots, on the cobblestones. And how old were you?

I was probably about 26. But if I did that today, I’d be in trouble, you know. I can do it in sneakers today, but not in boots.

So that was a moment where you were like, this is what this is about. And it changes you forever.

It does, it does. And it’s funny, I always keep a landline. Because when that bombing happened, the British government shut down all cell phones. But for a little time we had landlines, and that’s how we were able to communicate with people. And for that reason, I still have a landline.

So you and I met at the Oakland Book Festival. This was 2016. I remember vividly, I was sitting at a Litquake booth, outside City Hall there, and you came right up and you said, “I’m Cocoafly!” And you held out a business card, with a website and everything. And I looked at it, and was like, “Wow, she is organized.” [laughter] So what were you doing at that time?

I hadn’t gotten to KALW yet. I was freelancing and blogging, and I had been working for a nonprofit that did mental health advocacy in East Oakland. I was so excited that Oakland had a book festival. It was so good. I love watching C-SPAN Books, and how they go to different book festivals. I can see the energy. So when Oakland had a book festival, I was so excited. There’s so many great writers here, and we get to celebrate. I would love for Oakland to have a book festival again.

Yeah, the energy was really great. And it had a really intelligent, social-justice vibe throughout. I moderated a panel that year.

Yeah, I went to your Jack London panel.

Oh, where I mentioned that he was a white supremacist?

Uh oh! I’m leaving, did you see that?

Jack London’s great-granddaughter, she gave me such a look. Oh, man. I had to, though, right? You know, come on. The truth hurts.

People looked disappointed because they love Jack London, and it was like, what? I’m looking at all those white folks. I’m like, “Don’t look at me. I had nothing to do with that!”

Yeah, it got really quiet. And then I think there was one academic panelist who quickly chimed in, “Oh, well, you know, you have to understand, in context…” and he rolls out some sort of explanation.

This is why we need an Oakland book festival, because that was an Oakland moment. That was so Oakland! I really hope someone takes that mantle and brings it back.

So who are some of the more memorable interviews that you’ve done?

So many. Oh, Margaret Cho.

Oh, I love Margaret. I first met her when she was like 17 years old. I always liked her because she’s true, right?

Yeah, she is, she’s very down to earth. I know she doesn’t live in the Bay Area anymore, but just very much a Bay Area artist. So I enjoyed talking with her. Luenell, another comedian from Oakland. I really enjoyed talking to Luenell. I mean, it’s funny because when you interview comedians, they’re not always—

Funny?

Yeah. But they give really good interviews. Producing the interview with Mathew Knowles was really amazing. I’m trying to think who else. At the mental health nonprofit, I used to interview people who were learning how to manage their mental health challenges. Those were some of the most memorable ones that struck me. We tried to give people hope. And show different ways that people were managing their mental health, and that they were still able to have quality of life.

One more person I wanted to mention, who impacted me, Ericka Huggins.

Oh, she is amazing. She did a Litquake event one year, a discussion about the history of the Black Panthers.

Just being able to interview people who advocated, what they did, benefited me to be able to do what I do. She was incarcerated, and mistreated by the system. She has a very calming energy and presence and peacefulness. And it’s like, how do you have that after you went through so much, and your husband was assassinated? Definitely talking to her was unforgettable.

Those people who are still around in the community, it’s important to get those stories. So before we sign off, you don’t have to talk about this if you don’t want to, but I looked it up, and you were roughly a teenager during the O.J. Simpson trial?

I was 15, 16.

So when you were 15, this was all over the media. We all followed it on CNN. And your father was the co-prosecutor. What goes through your little teenage mind?

Well, I went to a predominantly Black Catholic high school in Oakland. And the trial highlighted the racial division in the country. So I was lucky that my classmates, with the exception of a few, didn’t harass me or be mean to me. One person who was mean to me, she actually apologized when she saw The People vs. O.J. Simpson series, years later.

Yeah, yeah. I could see that. “Oh, why is your dad doing this?”

Right. “Your dad’s a traitor to the race,” and all that kind of stuff. “Your dad’s a sellout.” I used to hear some of that.

That’s heavy though, when you’re a kid.

It is heavy. And then like, he’s on TV and people are criticizing him, and the rumors. I was in tabloids. My picture. My uncle’s ex-wife sold my Winter Ball picture to the tabloids.

What? Your Winter Ball picture?

Yeah, so when I came to school, it looked like a movie. I saw these people lined up at their lockers, all reading the Globe. And I was in it. I guess they went to the convenience store and got it.

And you’re like in some kind of fancy dress, and you’re 15 years old.

Yeah, and it was like, “Chris Darden’s Secret Love Child.” And I was like, I’m not a secret. Everybody—I’m not a secret.

Oh my god. I cannot imagine. For everyone watching the trial, we all realized that, at that moment, he had the toughest job in the United States.

Oh yeah. It was, it was, it was. Yeah. I mean, you don’t know until you experience something like that. It was challenging. I had my own phone, and I would get calls from the press. They just find you. They would call me and be like, “Tell us something about your dad.” And so for awhile, I didn’t even want to be a journalist.

I was going to say. That would turn most people off of journalism.

Yeah, I had wanted to be a journalist since I was a little kid. And then when the O.J. trial happened, I didn’t want to, because I was so disappointed with the press.

And you saw the worst part of it. The absolute worst part of the United States media.

Yeah. It was the worst. I mean, my uncle was dying of AIDS and there were reporters trying to crawl through his window, and break into the hospital, and all this kind of stuff. It was awful. And I didn’t want to be part of the media.

But I still had this longing to be a journalist. And so I just changed my outlook. I was like, well, you know, I’ve experienced this. So how do I be a better journalist? How do I make it better? I’m very committed to being ethical when I practice, because I know how it feels when people aren’t being ethical and they exploit you.

Right, right. That’s one of the things I wanted to compliment you on, is that you’re very, very positive in your radio segments. It’s like a joy. If you listen to one of your pieces you know it’s gonna be uplifting. It’s gonna be upbeat.

Yeah, it’s arts interviews, you know? Now about politics, it’d be different, right?

I totally hear you. All this journalism nastiness just reminded me. You know that there’s a museum in Guadalajara, Mexico, called La Casa de los Perros? The House of Dogs. It’s a beautiful neoclassical building in one of the big plazas downtown, and it has these concrete statues of dogs on the top of it. It’s a Museum of Journalism.

That's what it is? Oh my gosh! Wow.

So I’m guessing there was a period of time after the Bronco ride, and the trial and the verdict, you didn’t just immediately jump back into journalism. Did you have to re-evaluate, let it sit fallow for a bit?

I had to let it sit, I had to let it sit. And then towards the end of my time in college, I was still really interested in journalism. So I did this magazine internship. ’Cause that’s where my heart is. I can’t let a horrible national experience affect me like that. You know?

I mean, you could have changed your name or taken a professional journalism name if you wanted.

Oh yeah. For years, people would ask me, are you related to Chris Darden? I said no.

Really?

Oh yeah, for years. ‘Cause people hated him. And I’ve lost opportunities. I’ve interviewed for jobs, and then people wanted to know. I had interviewed for a Black newspaper in L.A. and they were interested in hiring me. And then they asked if I was related to him. And I said, well, yeah, he’s my father. And everybody’s face changed. And then I never heard back from them.

Come on. That’s fucked up.

It is.

I’m sorry to hear that. But you know what? I’m glad you stuck to it and didn’t change your name.

Yeah.

I didn’t know the whole Bay Area connection with O.J., until the local media took around a camera crew, here’s where he went to school, get a shot of a mural on a building or something.

Yeah, he went to Kennedy High School in Richmond. I still get contacted by the press, if he did something, or he’s in the news or something, or somebody’s trying to reach him. They’re not all vicious like they used to be, but you know, I still get contacted.

Yeah, well, it’ll be in your rear view soon. I mean, it pretty much is, right? Except idiots like me, bringing it up, you know.

I’m gonna get asked about it for the rest of my life. It’s funny. That’s okay though.

It’s been such a pleasure talking to you, Jeneé. Good luck with everything you’re doing and keep it up.

All right, thank you so much, Jack. I enjoyed talking to you too.