Hinckle, Hinckle, Little Star

There are two joys in life—making things and breaking things—and pirate journalist Warren Hinckle has excelled at both

Warren Hinckle: a classic San Francisco character. The first time I met him it was at a party for local politico Angela Alioto, at a dusty old mansion in the Presidio Terrace neighborhood. It was a strange old-school collection of assorted firemen, SFPD officer Bob Geary, who was fond of carrying around a ventriloquist dummy dressed like a cop, and private investigator Hal Lipset, who supposedly consulted on Coppola’s movie The Conversation. I hung around in the background near the food trays, which is where I first met Jane Ganahl, my co-founder of the Litquake literary festival. Hinckle was also there, standing alone sipping a beverage, and I introduced myself, and it was funny to realize that, like Jane and myself, that night he was just another freeloading journalist, lingering around for the food and open bar. I had heard a few notable stories about him, including his Hunter S. Thompson collaboration which gave birth to gonzo journalism. And I was friends with his daughter Pia, who is also now on Substack, check her out. So eventually I found myself researching deep into the Hinckle corpus of publishing triumphs and failures, lies and gossip, friends and enemies, pranks and alcohol, and his singular style of “rigorous fun.” This story first appeared on the cover of SF Weekly in 1996. Since it was published, more books have appeared which are worth noting: A Bomb in Every Issue: How the Short, Unruly Life of Ramparts Magazine Changed America (2010); and two posthumous Hinckle collections—Who Killed Hunter S. Thompson?: An Inquiry into the Life & Death of the Master of Gonzo (2017), and Ransoming Pagan Babies: The Selected Writings of Warren Hinckle (2018).

In the country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. —Desiderius Erasmus

Quentin Kopp barks into his car phone as he roars down I-80, another overcast afternoon commute for the senator to the Bay Area from Sacramento. The subject is his old friend, journalist Warren Hinckle, and the question: What has Hinckle contributed to the city?

“He’s stirred up some shit, that’s what he’s done!” exclaims Kopp in his characteristic growl.

“He’s the best writer in this city,” adds Kopp flatly. “Once in a while somebody can surpass him, but he’s your steady single- and double-hitter on what happens. He has the best instinct for the jugular.”

Has he ever directly picked on Kopp?

“Yeah, the prick got me about 1975. It was the first year Jerry Brown was governor. I’m trying to think of what it was. Some goddamn thing …” Kopp trickles off, experiencing a late ’60s/early ’70s memory block common to those who weathered the period in San Francisco. “I screamed at him, but, oh, the hell with it.”

Kopp says the first time he met Hinckle was in 1961 at a meeting of city politicians. The young Warren was decked out in a white linen suit, announcing his intention to run for city supervisor, demanding that the old-school political gentry listen to him and his ideas. He was all of 21 years old.

“He looked like a fop,” says Kopp. “He had the gall to think that he could serve with the likes of J. Joseph Sullivan or Harold S. Dobbs. I’m talking about the greats.”

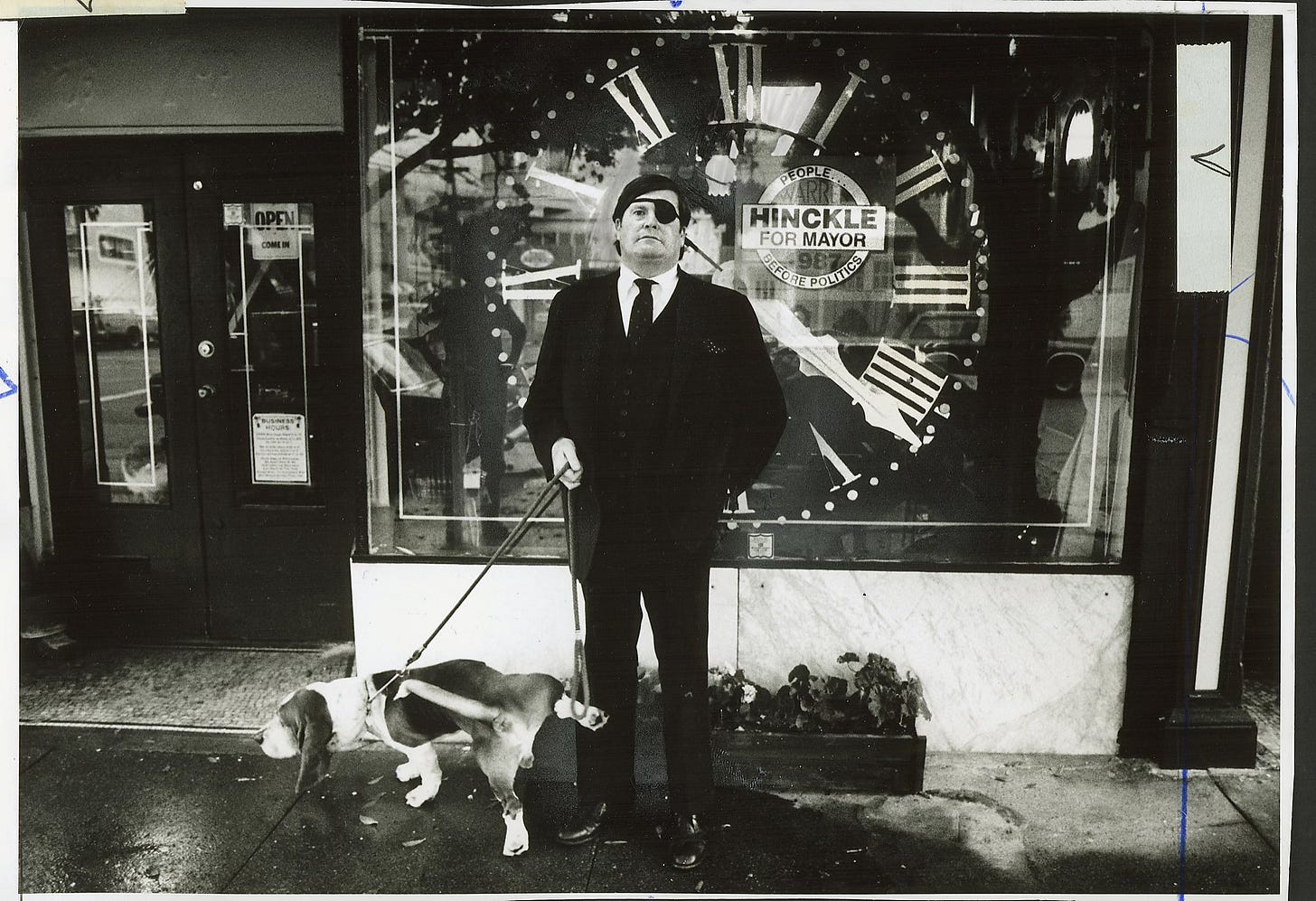

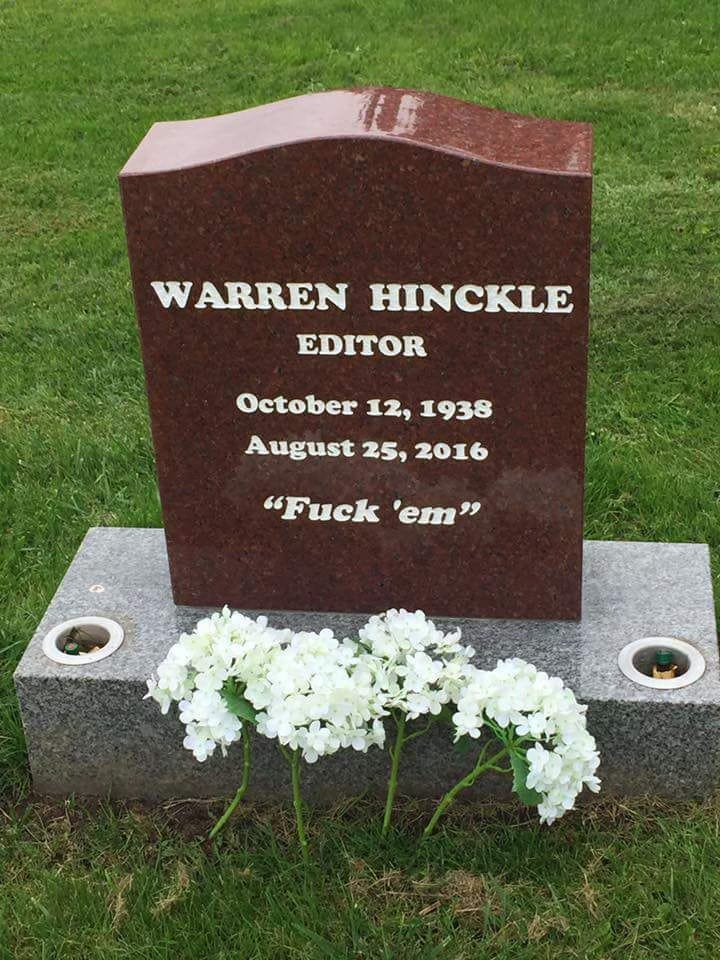

Linen suit or no, Warren Hinckle is many things to many people. He has been a public relations hack, magazine editor, muckraking reporter, columnist, procrastinator, mayoral candidate, con man, conspiracy theorist, and loving pet owner who recently held a pre-death wake for his ailing basset hound, Bentley, at Stars restaurant, feeding the mutt a final burger before the dreaded visit to the vet. Next to Herb Caen, he is arguably the town’s most well-known newsman.

The late Randy Shilts described him as “San Francisco’s foremost sob sister muckraking journalist.”

Hunter S. Thompson has said Hinckle is “the best conceptual editor I’ve ever worked with.”

“He’s a man who invents things, who often gets his facts wrong, who gets carried away by the emotion,” says veteran Chronicle reporter Maitland Zane. “He lets his prejudices dictate his writing. He’s not even a good speller.”

“I think he’s as good or better than Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson—he beats them all cold,” says Los Angeles Times columnist Robert Scheer.

Former Examiner staff editor David Beers reduces the Hinckle message to this formula: “We’re gonna take over the world, we’re gonna do it early enough to knock off for happy hour.”

“I think one can argue that everyone knows Warren is Warren, and don’t take everything he writes seriously,” says Examiner Executive Editor Phil Bronstein. “Some people take nothing he writes seriously.”

“He’s the Jimmy Breslin of San Francisco,” says longtime friend, collaborator, and former FBI agent William Turner.

“He will be a wonderful case study for future students of journalism, future students of publishing, future students of the political scene in this country—particularly the ’60s and ’70s,” says his aspiring archivist, Boston University professor Dr. Howard Gottlieb.

“He’s one of my best friends,” says political consultant Jack Davis, just before refusing to be interviewed.

“Isn’t he that guy who’s always drunk in North Beach?” asks my landlord.

But how did he get here? How does a one-eyed Irish Catholic son of a Hunters Point shipyard worker end up barhopping with senators and politicos, helping shoehorn mayors into City Hall? Well, don’t ask Jack Davis for help. Or Warren Hinckle, who also declined to go on record. As did other members of his family, frequent foils like Angela Alioto, certain journalists, and employers like former Examiner Publisher Will Hearst III. When Hinckle is informed of the strict code of silence Davis has adopted, he crows gleefully:

“It’s a conspiracy!”

Such high jinks breed mythology, a blur of fact and fiction that has always embodied the city, from the homeless Emperor Norton or the stray dogs Bummer and Lazarus on up to Kerouac or Kesey’s busload of white punks on dope. Reality and cartoon converge quickly in San Francisco; we find ourselves celebrating our loonies almost involuntarily, whether they be genuine nut cases or contrived attention-getters. And native son Warren Hinckle, known as much for his extravagant failures as heralded successes, as much for drunken political pranks as ball-busting journalism, proves to be no exception.

Hinckle’s impact is largely a memory now. The days in which he published assassination scoops, helped stop a war, uncovered nefarious CIA plots, published Che Guevara’s diary, and midwifed gonzo journalism twinkle like distant galaxies.

“I don’t want to contribute to furtherness of the myth,” says one of his former collaborators. “Just by writing a cover story on him you equate him with something important, and he ceased being that, oh, 20 years ago.”

But Hinckle, Hinckle little star’s impact remains palpable. He still writes a weekly newspaper column (for the Fang family’s Independent), he still cuts a swath on the party circuit, he still hobnobs and schemes with politicos, and up until two weeks ago he still had a basset hound. And he continues to prank practically every notable San Francisco politician and editor. Why, he must ask himself, should he bust his ass on the mundane like those sweathogs at the dailies?

Warren James Hinckle III was born in 1938, the grandson of native San Franciscans. The eldest of three siblings, he shared a fogbound house in the Sunset, a home where his 90-year-old mother still lives today, and where sister Marianne runs a book-printing company out of the basement.

After surviving 12 years of Catholic school, and landing at the Jesuit University of San Francisco, the curious young man observed that the school library carried The New Republic but didn’t stock copies of The Nation. He asked why, and was told that “one liberal magazine is enough.”

Hinckle became editor of the USF paper, the Daily Foghorn. According to his 1974 autobiography, If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade, written when he was only 36, he had a unique way of filling the paper. Once, when he needed a cover story, he enlisted a friend and burned down a wooden guardhouse in order to create some news. A hint of things to come.

In the early ’60s he was hired as a reporter by the Chronicle, working under the legendary Scott Newhall, who stacked the paper with columnists, strange journalistic hoaxes, and other techniques worthy of P.T. Barnum. The two were made for each other. Cub reporter Hinckle once was assigned to cover a press conference in which he was also giving a speech.

After his unsuccessful linen-suited bid for local politics, he opened a public relations firm that, by his own admission, was a disaster.

Between Chronicle stories, he was hired to help shopping center millionaire Edward Keating launch an intellectual Catholic journal named Ramparts, a publication for which Hinckle is perhaps still best known. Subtitled “The Catholic Layman’s Journal,” Ramparts ran such yawn-inducing articles as “George Santayana: Catholic Agnostic” and “The Theme of Waiting in Modern Literature.” Hinckle appeared in the Christmas 1963 issue as promotion director, and within a year had written for the magazine a firsthand account of a black Progressive Labor Movement march in Harlem that was abruptly canceled to avoid blacks fighting blacks in the streets, not exactly an image the Harlem community wished to offer the world. The article was timely, its subject was of genuine national concern, and it had absolutely nothing to do with the Catholic Church. It didn’t matter; the publisher was already $1 million in debt.

But with assistance from a hustling Hinckle, investors were soon found. He became executive editor, and was introduced, through each other’s wives, to a young journalist named Robert Scheer. Scheer offered a solid background in international politics, and his first feature ran in early 1965, a nasty indictment of the Catholic Church’s meddling in Vietnam.

“Hinckle got all excited,” remembers Scheer. “It was just what he was looking for.”

Scheer was hired as staff writer. Hinckle had also struck up a friendship with a San Francisco advertising whiz named Howard Gossage, who, truth be known, despised the ad game, and gained more pleasure from contributing articles to the magazine. Media savvy told Gossage that Ramparts needed a visual overhaul. He called a designer friend from L.A., Dugald Stermer, and put him in touch with Hinckle.

“Warren told me that they had enough credit for two more issues,” says Stermer, “and that the founder was down to his last shopping center. Yeah, why not. I only had three kids and a wife; it wasn’t like I was encumbered.”

Now the three had an entire magazine at their disposal. They were faced with a turbulent mid-’60s political climate—an unjust war, assassinations left and right, unchecked corporate corruption—and nobody was covering it.

“It was a time for intellectual gunslingers,” says David Burgin, at the time a sports editor for the Examiner. “You had to have a lot to say, and a different way to say it.”

They had a lot to say. Ramparts broke stories on the Michigan State University connection with the CIA, persecution of the Black Panthers, the JFK assassination, and the RAND think tank. They printed the story of a decorated Vietnam veteran who came out against the war. An Oakland City Hall corruption feature reportedly was instrumental in forcing then-Mayor Houlihan to resign. One issue was composed entirely of excerpts from the smuggled diary of Che Guevara, including an introduction by Fidel Castro himself.

A cover story by Hinckle called “A Social History of the Hippies” provided plenty of Haight and Fillmore photos for the ’60s stoner culture to drool over, except some staffers actually read the essay and resigned in protest.

Stermer splashed full-bleed illustrations across the pages—angry caricatures of politicians and photo essays of subjects like the 1968 Chicago riots or a North Vietnam all-girl militia. The art director blasted the self-congratulatory media establishment by nominating Adolf Hitler for the Father of Modern Advertising, for Der Führer’s simplicity of the swastika logo. Covers leaped out at readers—Jesus crucified on the cross in the middle of a Vietnam battlefield, a JFK portrait made out of puzzle pieces, a close-up shot of hands of the editorial staff holding up burning draft cards.

Ramparts’ roll call of contributors was also impressive—Martin Luther King Jr., Noam Chomsky, Jessica Mitford, Kurt Vonnegut, I.F. Stone, Studs Terkel, and Richard Brautigan, as well as jailhouse letters from Jack Ruby, Eldridge Cleaver, and Ken Kesey. The magazine even had its own “spook desk,” manned by former FBI agent William Turner.

“What we were writing was what the mass media should have been doing and wouldn’t do,” says Scheer. “I was in the mold of the New York Jewish intellectual. Dugald was supposed to be the L.A. lifeguard, and Hinckle was supposed to be the San Francisco drunk.”

Hinckle’s cohorts watched his persona begin to emerge.

“He had a drooping eyelid, and a blind eye,” says Stermer. “The muscles had been damaged in a childhood accident. He went in to have an operation to pull up the eyelid. It would require two operations, and after the first one the doctor said, ‘Wear an eye patch,’ so he did. And he liked it, and never went back for the second operation. He started adding to the image, you know, a velvet suit, or a pair of dancing pumps, and adding his dog.”

“I don’t understand the thing about the dog,” allows Scheer. “I don’t know what that’s all about.”

When money ran short, Hinckle and company traveled around the country shaking down potential investors, whether they be Columbia University debutantes, suit-and-tie liberals, or wealthy clients of a proctologist friend. The magazine was always broke, but they were all in their 20s, what did they have to lose?

Offices were moved from San Mateo to North Beach, in close proximity to local bars like Vanessi’s, where staff meetings ran far into the night. By 1967, circulation had risen from 2,000 to an astounding 228,000 copies infiltrating the country. There was nothing else like it—glossy and subversive, a welcome antidote to the sanitized drivel of Time magazine. For America’s rebelling youth, a national magazine finally spoke to them.

Ramparts won the George Polk Memorial Award for excellence in journalism, and became the subject of a 12-minute report on the Huntley-Brinkley nightly broadcast and front-page news stories in The New York Times.

“I think hesitation would have been our downfall,” recalls Stermer, now a San Francisco graphic designer.

Such notoriety made for interesting encounters with strangers. One story has it that sometime in 1967, after reading the galleys of a forthcoming book, Hinckle invited the author—Hunter S. Thompson—to the North Beach office for a visit. Thompson set down his knapsack, and the two left to go drinking. When they returned they discovered Henry Luce, the office monkey, had escaped from his cage, opened up the knapsack, sampled some bottles of pills contained therein, and was currently tearing around the office, screeching at the top of his lungs. It took the simian two days to return to normal.

The delicate nature of some of the editorial material made for some certified paranoia during those Cold War days. William Turner remembers opening up the Ramparts office one morning to discover the entire place had been trashed. He called police, and a sergeant arrived to inspect the scene and take notes. Turner immediately thought, “Oh, some right-wing jerks had a buzz on, and decided they’ll get even with them for publishing all that lefty trash.” The crime remained unsolved until years later, when Hinckle couldn’t stand it any longer, called up Turner, and confessed everything. He had gotten drunk one night with contributor Gene Marine, and the two had destroyed their own office.

The staff was never at a loss to spend money. Hinckle and Scheer flew first class whenever possible, and rang up enormous hotel bills. In 1967 the magazine launched a weekly Sunday newspaper offshoot, in which toiled a young entertainment reporter named Jann Wenner, running errands in his mother’s Porsche. When San Francisco newspapers staged a strike in early 1968, Ramparts published a daily edition, and later in the year, during the Democratic Party convention in Chicago, they published an oversize version of their daily from the hotel.

But by the end of 1968 the strain was beginning to show, and the organization filed for bankruptcy. Another version resurfaced the following April, with Scheer and Stermer still at the helm, but Hinckle was gone to New York. He had another idea.

Together with Howard Gossage and journalist/attorney Sidney Zion, Hinckle was planning a successor to Ramparts, jokingly named Barricades. The project found investment capital, and Scanlan’s debuted in early 1970, co-edited by Hinckle in San Francisco and Zion in New York. The first issue’s cover featured a reproduction of their initial $675,000 investment check, and a subsequent one of a fist punching President Nixon in the face.

Scanlan’s is best remembered not for Hinckle’s pranks but his collaboration with Hunter Thompson, who pitched the idea of covering the Kentucky Derby. Hinckle suggested British illustrator Ralph Steadman as a traveling companion. Steadman accepted the assignment, and his first visit to America ended up a frantic, alcohol-soaked blur of a week in Louisville, Ky., his fish-out-of-water reactions becoming the centerpiece of Thompson’s notes.

The two flew to Scanlan’s New York office to piece together the article: Thompson was sequestered in a hotel to finish the text, where he found himself up against the wall with terminal writer’s block. Scanlan’s was panicked—it had 12 blank pages to fill and time was running out. Desperate, Thompson ripped out a few scrawled pages from his notebook and turned them in, knowing they would be angrily rejected. Instead, Hinckle called him from San Francisco and loved it. Send more. Thompson finished his high-octane first-person collage of observations and sentence fragments, which were forwarded to Hinckle for editing, and slunk back to Aspen, certain he had blown it.

“The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” appeared in Scanlan’s June 1970 issue, and its narrative structure of fragmented, unrestrained chaos was, at the time, completely original, Steadman’s brutal images adding to the mix.

“It was awesome,” remembers Burgin, now executive editor of the Alameda News Group. “It was just incredible.”

The piece is acknowledged as the origin of gonzo journalism, and has spawned endless imitators from Rolling Stone on down to today’s zine explosion—inspiring and ruining writers for a generation to come.

Despite its notoriety, Scanlan’s never found secure financial ground. In 1971, the final issue’s entire print run of 200,000 was seized at the Canadian border, supposedly on orders of the Nixon administration, and Warren Hinckle found himself riding another nag into the dirt—the second magazine in three years. He snatched up the unused editorial content and wrote his first book, Guerrilla War in the USA.

No more Scanlan’s meant more time with the family. Hinckle was living in the Castro with his wife and daughters Hilary and Pia. He would entertain his daughters and their friends by popping out his glass eye and flicking it between his teeth. The Hinckle household became well-known for its Thanksgiving get-togethers. One year a lawyer friend of Hinckle’s brought over a vial of amyl nitrite, and passed it around to the adults. Hippie satirist (and neighbor) Paul Krassner remembers taking a sniff and just for fun passing the vial to Quentin Kopp, who exclaimed:

“What’s this for? I don’t have polio!”

“I’d go to his house and there were piles of newspapers and magazines and clips and notes from telephone calls, and his dog sitting there looking like Sherlock Holmes’ bloodhound,” says Krassner. “He would be grunting and grumbling, and I would say to him, ‘Warren, don’t you remember the time when it was a pleasure to write?’ and he would grumble to me, ‘It was never a pleasure.’”

Hinckle’s second book, The 10-Second Jailbreak, published in 1973, grew out of William Turner’s investigations of a prominent wealthy liberal named Jack Kaplan, whose sugar company had been linked to Caribbean operations of the CIA. Kaplan’s nephew was imprisoned in Mexico City for a murder he said he didn’t commit, and after several escape attempts failed, a helicopter flew to his rescue. Hinckle, Turner, and Eliot Asinof shared the byline, and the book was eventually made into the movie Breakout, starring Charles Bronson, which Turner now laughingly calls a “real potboiler.”

Hinckle’s next book grew out of the ex-CIA pilot whom he and Turner had also bumped into who had entree to Miami’s anti-Castro Cubans. Turner flew to Miami, using his old FBI contacts to research the idea.

“Warren’s job was to polish, rewrite my stuff,” remembers Turner, but the anti-Castro project was to be delayed for years, because Hinckle had gotten a contract to write his own memoirs, and the publishers sequestered him à la Thompson in a New York hotel to complete it.

“The research was all done,” says Turner. “I just never gave up on it.” Nine years later, The Fish Is Red: The Story of the Secret War Against Castro would finally be published, a comprehensive tale of CIA-Mafia espionage and mercenary activity involving Castro and the Kennedy assassination.

Hinckle’s autobiography arrived in 1974, an audacious chronicle of the ’60s and the years at Ramparts. Studs Terkel called it “a hilarious and serious commentary in one,” but the other Ramparts members were somewhat dubious.

“It’s a terrific work of fiction,” chuckles Robert Scheer.

Graphics designer Dugald Stermer is much less generous: “An autobiography by somebody who’s afraid that he might be forgotten.”

Hinckle leaped right back into magazines, this time seducing the bulging pockets of Francis Ford Coppola, at that time coasting on the success of The Godfather, and intrigued with the idea of creating a media empire outside Hollywood. Coppola and Hinckle devised a more local publishing concept, a magazine called City of San Francisco. Hinckle hired a staff, offices were rented—again in North Beach—and it was off to the races. In inimitable Hinckle style, City wouldn’t last long, but it would make a splash.

San Francisco was wilder in the ’70s than the ’60s. The endless free-love party trickled uphill to the establishment, where everybody had money to burn. People elbowed for space in fern bars and topless joints, the Mitchell Brothers were porn’s Katzenjammer Kids, Margo St. James was organizing an annual event called the Hooker’s Ball, comedy clubs were sprouting, politicians were passing joints to cops at parties thrown by lawyers, Bill Graham was throwing Day on the Green concerts in Oakland, and Cyra McFadden was satirizing the hot-tub Marin lifestyle for the Berkeley Monthly. Each year, thousands of gays were migrating to the city and settling in the Castro. Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City was running regularly in the Chronicle.

Against this backdrop of insanity, City attracted attention by posing on the cover of the debut issue a young woman seated on a barstool between two disinterested men. Underneath ran the headline: “Why Women Can’t Get Laid in San Francisco.” The issue sold out.

Like other Hinckle publications, the organizational principle was chaos. Coppola assigned someone to follow Hinckle around town, with orders to drag him out of bars during deadline. Contributor Paul Krassner’s $150 payment for an article was delayed so often he finally visited the magazine’s offices and threatened to heave a typewriter through a window. The managing editor was forced to make a phone call to Coppola’s wife.

“I got a signed check within 20 minutes,” remembers Krassner.

Hinckle took Krassner aside later and told him, “You did the right thing.”

Within months, Coppola realized the downward direction of his investment. Singling out the primary source of the problem one evening at a party, he shoved Warren Hinckle into a swimming pool. Hinckle surfaced soon with yet another start-up, Frisco, a direct jab at Herb Caen’s long-standing admonition not to call it such. Frisco sank not long after its launch.

Undaunted, Hinckle returned to the Chronicle and began a column called “Hinckle’s View.”

On Nov. 27, 1978, ex-cop, ex-fireman, and Pier 39 potato vendor Dan White expressed his frustration at not being re-elected city supervisor by executing Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk.

Disgusted by soft reporting about White in the daily papers, Hinckle investigated and wrote that the murderer had been congratulated by police officers upon his arrest; that he was brought a roast beef sandwich every day in jail; that he never once expressed remorse, sitting in his cell, hands behind his head. Despite the city’s reputation for tolerance, anti-gay factions were still very much alive in certain districts such as the Sunset, home turf to both Hinckle and White. But neither San Francisco daily would report negatively on White until after the trial, according to the 1982 book The Mayor of Castro Street by Randy Shilts, and for the moment, Hinckle was forced to sit on his research.

In May 1979 the jury returned a verdict of voluntary manslaughter, a seven-year sentence. The city was outraged, and City Hall was stormed. Police cars were set ablaze, anarchy was in the streets, hereafter known as the “White Night” riots. Hinckle witnessed firsthand a police charge into a Castro bar called the Elephant Walk, where cops clubbed gay patrons and bartenders with batons, yelling, “Sick cocksuckers!”

In 1985 Hinckle would publish Gayslayer!, a spirited, passionate collection of his stories from the Los Angeles Times and the Chronicle, illustrated with photos of the riots, as well as a manuscript reported to be Dan White’s actual jailhouse diary. By this time he would also have published two other books, The Richest Place on Earth (1978), with Fredric Hobbs, about early Virginia City, and The Big Strike (1985), a pictorial history of the 1934 labor strike. But a noticeable shift in direction was occurring.

Hinckle was turning his sights inward, toward the city and California, and, in a way, to himself. No longer did he seem to be concerned with the big stories. There were no more riots in the streets to cover, and he’d already helped stop a war.

Hinckle continued to juggle the twin passions of agitprop and journalism that had entertained so many, but he subtly turned up the volume on the theatrics. By living large and pulling a few fast ones, he learned that the stories would all but write themselves—and nobody would dare edit him. The beauty of prank journalism was that if the stunt was good enough he could put a story in play—and keep his name in print—without committing any words to paper himself.

The Hinckle persona rang loud and clear at the 1984 Democratic National Convention. While then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein was sweeping the homeless away from Moscone Center, Hinckle helped established a rump press headquarters at the O’Farrell Theater HQ of DiFi’s personal nemeses, the Mitchell Brothers—Jim and Artie. Hinckle was partner with the Mitchells in the Feinstein business: He wrote so many columns about her that one night she poured a drink over his head.

The Mitchells were such frequent targets of police raids that they retaliated against Feinstein by posting her unlisted phone number on their theater marquee: “Showtimes call Mayor Feinstein 558-3456.” (Note to readers: Don’t phone the number. It now belongs to Neighborhood Emergency Response Team Training.)

When Behind the Green Door porn star Marilyn Chambers performed live at the O’Farrell Theater, schoolmarm Feinstein put her foot down: Upward of a dozen cops raided the theater, hauling Chambers and her bodyguard away for prostitution. Chambers’ release from jail was delayed because officers kept requesting to take Polaroids of her in her cell. The bust was ridiculous on many levels, and immediately became the buzz of the town.

Warren Hinckle immediately assessed the incident in his Chronicle column:

“These porn dancers can be dangerous; one has to watch closely to make sure they don’t pull a concealed weapon from some orifice.”

His article appeared with an illustration by R. Crumb depicting Chambers being hustled down the street by a pack of chest-puffed policemen, exclaiming her jailhouse quote: “I don’t take tips, so how could I be soliciting?”

For his efforts, Hinckle was marked for arrest by the SFPD. His name was run on a computer search, and the results posted on a police station bulletin board for all to see: the unforgivable horror of a 4-year-old violation in Marin County for expired plates. Several days later the columnist was arrested in front of the Chronicle building by two officers. In addition to the traffic violation, he was also charged with the heinous crime of walking a dog without a leash, and hauled off to the clink. The paper ran the photograph, and Hinckle proudly described his brush with the law:

“You Hinckle?” one of the cops asked.

“I allowed I was,” wrote Hinckle. “It’s hard to hide if you’re fat and wear an eye patch.”

This wasn’t a CIA expose, but it was headline material—one citizen against the cops. Hinckle paid $178 in fines and was released, and two days later wrote a column about then-Police Chief Con Murphy. It seemed the chief’s boat was berthed at Fisherman’s Wharf, but obvious favoritism was being shown upon the head lawman, because the berths were supposed to be reserved for commercial fishing boats, not pleasure boats.

The Chronicle bumped the column to the front page, accompanied by an incriminating photo of the chief, casually putzing around on his prized vessel. Hinckle then tallied the approximate cost to taxpayers in police overtime to bust the Mitchell theater and arrest Chambers—$203,000. Then-Police Commissioner Jo Daly received over 50 calls from citizens protesting the Chambers raid. Hinckle’s arrest was publicly denounced by the California Newspaper Publishers Association, and for once, Feinstein agreed with him, saying, “It was dumb, dumb, dumb.”

The excitement was not lost on William Randolph Hearst III, who had just taken over his grandfather’s Examiner newspaper and wanted to reinvent the Monarch of the Dailies. The plan was to stack the newspaper with lively personalities. Hinckle was the first. David Burgin came aboard from the Miami Herald, and Hunter Thompson was convinced to sign on, as well as Cyra McFadden, Joan Ryan, Rob Morse—even Herb Caen was nearly persuaded to defect.

Hearst had his dream team; Hinckle and Thompson were reunited again. Hinckle picked on the cops and other local hypocrisies, and Hunter roared off on various adventures, composing disjointed screeds against the national political swing to the right. And they were driving the rest of the paper crazy.

“They’re incorruptibly corrupt, both of those guys,” remembers Bob Callahan, Hinckle’s research assistant at the time. “They’re nuts, and you’re not going to get them to moderate their behavior under any circumstances. Neither one of those guys knows what time it is. There were guys that were hired—their whole job was to chase these guys around all day, trying to get copy out of them. Here’s the whole Damon Runyon, Ben Hecht, goofy universe that I saw movies about, being re-enacted live. And they kind of knew that’s what they were there for.”

Hinckle relished his growing celebrity. Callahan recalls attending an industrial art performance in a South of Market parking lot with the columnist and his friends.

“We had to walk by the stands, and when Warren walked by with Bentley they all started applauding him—all these fucking kids,” Callahan says. “They knew who he was. It was like, man, isn’t it great that Warren Hinckle comes to these events.”

In 1987, the Examiner marked its 100th Hearst anniversary. Will Hearst assigned Hinckle to edit a special centennial package composed from Examiner back issues, and Hinckle brought on Ramparts art whiz Dugald Stermer and Callahan. The team was entrusted with keys to a subbasement in the old Hearst building that housed 40-foot stacks of Examiners dating back a century. Callahan stood in awe.

“It was like the real vault that Geraldo wanted to find in Chicago,” says Callahan.

The three assembled a weeklong series of daily supplements, primarily reprints of old Hearst contributors—Jack London, Mark Twain, George Herriman, Ring Lardner, Ambrose Bierce, Damon Runyon, and others.

Reporters from the BBC snooped around the project, recognizing Hinckle and Stermer from Ramparts, and asked them jokingly:

“How can two commies like you end up working for Hearst?”

But the taillights of the Ramparts era had receded into the distance, according to Stermer:

“Warren would go to the bar, and I would do the paper at the office. I don’t think anybody during those nights and days, even with the Hinckle apologists, would claim that he had any impact on the thing. He would be in and out, and he’d scream, ‘Oh, why’d you put this to bed, I was going to write something!’ and I would explain, ’Fuck you,’ and that would be it. Will would come in at 2 in the morning and say, ‘Where’s Warren?’ and I’d say, ‘Who?’”

Dusting off old Examiners in the stacks wasn’t the first time Hinckle had plundered the archives for inspiration. Callahan, now the editor of Avon Books’ Neon Lit series, remembers one afternoon waiting in Hinckle’s personal library for a meeting with the man.

“This is where all the debris of all the magazines went. It was amazing to me, because it was all these journalists that I had never read, like the complete Gene Fowler, the complete Ben Hecht, the complete Mencken. Everything these guys ever wrote -- every book. I opened the books, and they were underlined. And then I realized, Warren Hinckle invented Warren Hinckle, to fit this tradition that he imagines himself in the middle of. The dress, the dog on the leash. I realized, here’s a guy who had gone to journalism the same way a lot of artists had gone to art, this sense of inventing his own role in it and then living it out.

Callahan continues: “He made himself up, and in this town you can. This is a shy, overweight one-eyed Irish kid who decides he’s gonna just invent himself as Warren Hinckle, living successor to Ben Hecht, Gene Fowler, and Lucian Beebe. And he did. And he is, and it’s a great fucking story. He had impact on this town over and over again, and he’s not through yet.”

“I think Warren is a lot smarter than he thinks,” says Robert Scheer. “I think he had an inferiority complex, really, about not being an intellectual, about not being really educated, and not being from New York, not having gone to one of those schools. And so as a result, he always felt he should report on what he knew about bars, or Irish San Francisco. I always felt that was his biggest problem.”

But if one consistent philosophical thread runs through Warren Hinckle’s work, it is sympathy for the working man. Like Old Man Hearst 100 years before, he insists on fighting for the little guy.

“He’s sort of an old liberal, which is different than a modern liberal,” says Zoran Basich of the San Francisco Independent, where Hinckle’s column now appears. “He’s not real politically correct, but he is for the underdog.”

Underdogs might need to reach for an unabridged Webster’s to fully comprehend some of Hinckle’s prose, which is often peppered with arcane turns of phrase, antiquated language, and references to Henry Fielding novels.

“As I read his stuff, there was always one word that I had to look up,” says Paul Krassner. “He told me that he always deliberately put one word in it that had to be looked up.”

Callahan also attributes the peculiar Hinckle spin to a strong heritage of Irish writers.

“I think if you’re Irish and you’re writing in English, you have a really interesting relationship with the language you’re writing in. You’re constantly trying to subvert it as you make it work. Because it’s English, it’s not Irish. You like to make it work better than it actually did before, by breaking its own rules. And that’s what it’s like to be Irish.”

In August 1987, Hinckle agitprop became more overt when he ran for mayor. In an Examiner column, Hinckle listed his civic accomplishments:

“I exposed the slumlord heatcheats who froze our senior citizens in Tenderloin hotels in winter…I was the first straight journalist to decry the ugly wave of gay-bashing in this town…When three San Francisco fishermen died when the drag boat Jack Jr. was run down by a killer tanker, I spiked an attempted cover-up on the part of the ship’s owners and campaigned to make the sea lanes safe for our fishermen…[E]ven though Madame Mayor was against it, I managed with the public’s overwhelming support, to change the city song from the smarmy ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco’ to the robust ‘San Francisco,’ from the best movie ever made about this town.”

Not to mention that business about turning Alcatraz into a casino.

Hinckle explained to his readers he would be “going on vacation.” Will Hearst III said Hinckle would be welcomed back to the Examiner after he “wins, loses, or withdraws” from the race.

In true San Francisco fashion, a variety of half-serious candidates expressed interest in running for office that year, including comedian Will Durst. Somebody had the bright idea of staging a mayoral debate between Hinckle and Durst, moderated by Jello Biafra, at the Mission’s Victoria Theatre.

“He showed up late,” says Durst of the evening. “He had some other Irishman debate me.”

An hour later Hinckle arrived, and the event proceeded. Who won?

“I did,” Durst says. “Oh yeah, easy. I was sober.”

When Art Agnos won the election, Durst went back to comedy clubs and Warren Hinckle went back to writing Examiner columns.

By this time Hinckle had earned a reputation as an editor whose magazines were forever crashing into a mountainside, yet he always managed to dust himself off and stroll away from the wreckage. Astonishingly, and certainly against their better judgment, people still gave him more opportunities. Will Hearst was going to give him one more, handing him Image, the Sunday Examiner magazine. It will be like People, Hinckle promised, except with occasional hard-hitting exposés! We’ll get art director Roger Black to give the whole thing a face lift!

David Beers, then editor of Image, was assigned to help Hinckle. He knew the Hinckle horror stories—the abrupt last-minute scrapping of one idea in favor of another, the dozing off drunk at the computer terminal, the staff begging him to dictate his column word by word, Bentley snarfing the contents of brown-bag lunches. He wanted no part of it, but since he was only 29, he had no cachet whatsoever. He struck a deal with the Examiner that he would work as Hinckle’s managing editor for five weeks, and insisted his name appear nowhere on the masthead.

The tension was immediate. According to Beers, Hinckle arrived each morning around 11, tore up all the work the staff had done to that point, would go out to a long lunch, come back around 3 p.m., tear up any other work that had been accomplished, and leave around 6 to go out drinking, with strict orders everything had better be completed by the following morning.

About week four, Beers had had it. Hinckle had barreled out the door one evening, as always, telling the staff everything had to be redone. It was going to be yet another long night, racking up more overtime that was undoubtedly to be fruitless. Beers told the staff, Screw it, everyone go home.

“They were close to mutiny at that point anyway,” he remembers.

Beers went out to dinner, and when he returned home, he found his wife lying in bed with all the lights off, huddled in terror.

“There’s a strange man on the answering machine, threatening you,” she said.

Beers played the message, and heard the unmistakable voice of Warren Hinckle, calling from a bar.

“You are guilty of insubordination,” snarled Hinckle, “and I will take this up with the highest court of the Hearst Corporation.” The tape continued, ordering Beers to be back in the office at 6 a.m., or face the consequences. At the end of the message, Beers heard Bentley bark in the background.

Beers arrived at the Examiner the next morning, answering machine tape in hand, eager to talk to Executive Editor Larry Kramer. To his surprise, Kramer approached him first.

“Did you get a phone call from Warren last night?” asked Kramer.

So had Kramer. After a short discussion, Beers was offered another job on the paper. Hinckle strolled into the Examiner around 11:30, and not a word was ever mentioned about the phone calls.

The episode was recounted in the East Bay Express by Sean Elder, who wrote, “Obviously by now, anybody can tell that giving your magazine to Warren Hinckle is like asking Roman Polanski to babysit your teenage daughter.”

Hinckle was eventually eased out of Image and plopped back into his column, which continued from New York, where he now made his home. After an amicable divorce, in which Quentin Kopp had handled both sides, he had married novelist Susan Cheever, and the two now had a son, Warren Hinckle IV.

Hearst was unhappy with Hinckle writing a local column from New York, a point that Kopp doesn’t buy. Even from afar, the senator says, Hinckle can still write better “day in, day out, what’s happening in San Francisco.”

The newspaper’s ultimatum was either live here, or lose the column. In January 1991, the columnist was fired.

A few days later a motley menagerie of noisy Irish, old hippies, and others converged on the Examiner building. They protested that Hinckle had been fired for writing a column critical of the Gulf War that compared President Bush to Tojo, a column that the Examiner was too chicken to run. The atmosphere was that of a drunken circus. A 10-foot-tall replica of George Bush’s head stared at passers-by from the bed of a truck. Flasks were passed to warm up the chilly morning. Strippers wobbled on their high heels, carrying picket signs with slogans like: “Stop Harassing the Visually Impaired.”

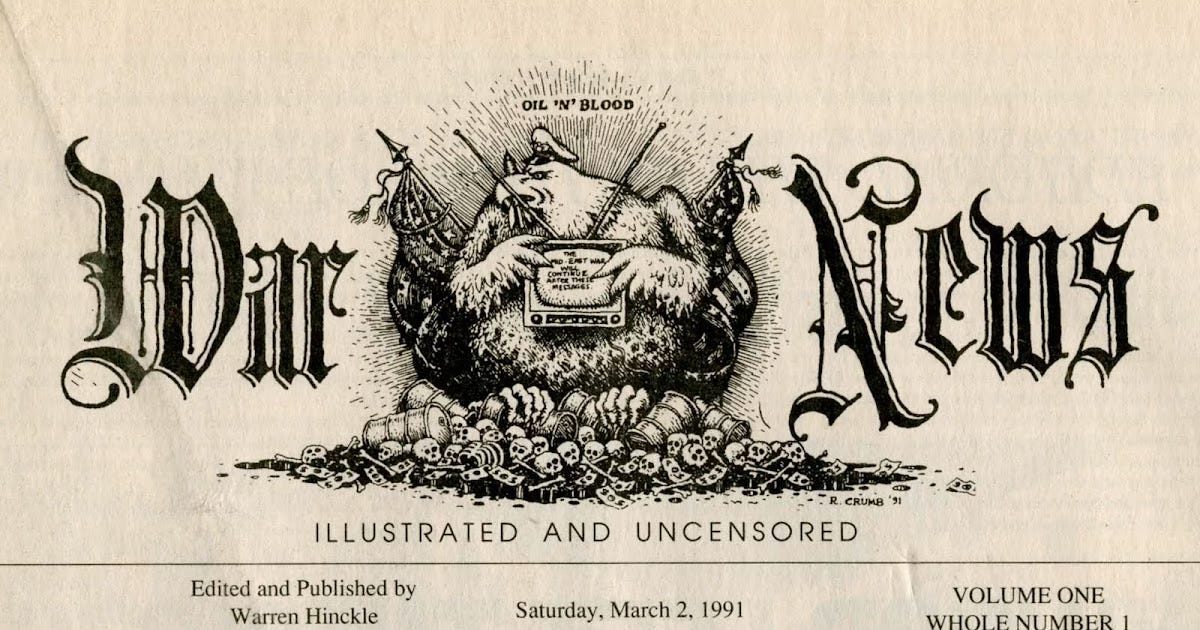

Jim Mitchell seized the opportunity to expand from the porn business and launch his own newspaper, to combat the disinformation America was receiving about the Gulf War. It was called War News, and Mitchell appointed Hinckle as its figurehead editor/publisher, whose primary duties were riding around in a car from bar to bar with his dog, while everyone else did the work.

A nightclub in North Beach was opened as an office. Hinckle commuted back and forth from New York, calling in favors and rounding up contributors, including Barbara Ehrenreich, whose Time magazine piece had been killed, as well as Daniel Ellsberg, Michael Moore, Paul Krassner, Art Spiegelman, Ron Turner, Bob Callahan, Peter Bagge, Jim Woodring, Trina Robbins, S. Clay Wilson, even a fax from Hunter Thompson. R. Crumb designed a logo. T-shirts were printed up.

Callahan was amazed at the array of talented shit-disturbers they had attracted for this one last tweak of the establishment. “It was like ‘The Over the Hill Gang’ gets one more ride on the range.”

Hinckle was back in his element, ear glued to the phone. This wasn’t some bullshit Sunday magazine— it mattered. And like most of Warren Hinckle’s gut instincts, at heart he was absolutely right. Hinckle didn’t get a chance to kill War News, though. Jim Mitchell did by shooting to death his brother, Artie. (Thanks to a Hinckle-led publicity campaign, Jim Mitchell got only six years.)

From his perch in New York, Hinckle began writing a weekly column in the Independent that slammed then-Mayor Art Agnos. His confederate was campaign consultant Jack Davis, who just happened to have a candidate in the race, former Police Chief Frank Jordan. A collection of the vituperative columns called The Agnos Years was published just days before the 1991 election, with Hinckle signing copies on the steps of City Hall. Jordan unseated Agnos, and Davis toasted Hinckle on a job well done. At the end of the year, Hinckle negotiated a fee with the Independent and began a regular column.

Borrowing a long-dead title of a newspaper founded a century ago by Ambrose Bierce—The Argonaut—Hinckle launched yet another publication. Actually he launched two, an eight-times-a-year free newspaper and a quarterly literary journal that went by the same name. Editor/Publisher Hinckle promised that it would compete with Granta. “We will bury them like a moldy dog,” he wrote in his opening editorial.

Argonaut offices were established in a ramshackle building on Geary Boulevard, owned by Joe O’Donoghue, president of the John Maher Irish Democratic Club. Roger Black graciously designed a template. John J. Simon accepted a senior editor post. Ishmael Reed signed on as literary editor. Daughter Pia became managing editor. More old names reappeared from the past, from Studs Terkel to William Turner and Sidney Zion.

The quarterly was occasionally brilliant, such as the second issue’s exploration of Germany’s burgeoning neo-Nazi movement. The third issue was delayed for months, however. Staff members came and went, including the firing of Pia Hinckle by her father. “Crazies: Is America Going Nuts?” was eventually published, but the advertised fourth issue, discussing the “Phenomenon of the Vanishing Jew,” was never completed.

The newspaper edition of The Argonaut quickly devolved into an occasional throwaway, published mostly in the vicinity of local elections, stocked full of ads from Hinckle’s political pals and attacks on his enemies. During the last mayoral election, the paper published a Photoshop-faked picture of Jordan in the altogether—the man they had helped to elect in 1991. Hinckle’s choice for mayor this go-round? Jack Davis’ candidate, Willie Brown.

Davis has filled an obvious void in Hinckle’s life. He has a partner-in-crime once again. Cut to the Mitchell Brothers’ theater in 1994, a Sunday afternoon birthday party for local politico Barbara Kolesar. As guests milled about, chatting and drinking, suddenly loud music cranked up from the sound system, a hybrid Don Ho/Ohio Players disco thump. The showers activated in the fabled Shower Room. Some sort of show was about to begin.

But it was to be a performance that would forever haunt the dreams of all assembled. Stepping out from the wings were not two nubile, naked women, but Warren Hinckle and Jack Davis, Hinckle wearing red checked boxers and patent leather shoes, Davis parading around in B.V.D.s. The crowd was slack-jawed at this tableau of two rotund, nearly nude men, drinks in hand, frolicking under the shower heads. Bentley suddenly recognized his master—perhaps it was the checkered boxers—and, despite a bandaged paw, eagerly jumped into the shower. As the columnist attempted to calm his excited dog, Bentley’s soaked bandage began to unravel. A silent crowd fumbled for their cameras.

Despite all the public pranks and moldy magazine carcasses, Warren Hinckle remains audacious in his Independent columns, issued weekly from the Argonaut office. Chronicle columnist Phil Matier is dismissed as a “toilet brush.” Examiner Executive Editor Bronstein is alleged to have a secret latent homosexual crush on Jack Davis. Bay Guardian Publisher Bruce Brugmann is said to sport “well-manicured fingernails.” And this very newspaper represents “square-headed yuppiness,” in Hinckle’s words.

“I think that it’s Warren as catalyst that makes him important, more so than Warren’s own ideas,” says Boston University’s Dr. Howard Gottlieb, “which of course are numerous, and go in all directions.” Gottlieb is eager to collect Hinckle’s work and papers at the BU Library, and has pursued the man relentlessly since 1965. He compares his quest to a minuet:

“He would promise yes, I would send truckers, and archivists to help pack the materials, and something would develop, and they would come back without the materials. This went on year after year, and each time Warren had another excuse. Oh, he had to leave town, or Ramparts was going into bankruptcy, or he had to think of something else, or this would happen, or that would happen. I’m hoping that as he lopes into maturity, and as the onset of middle age comes upon him, he may be tired of carrying all this material around. And then I think he might weaken. And I’m ready to pounce when he does.”

Robert Scheer is quick to point out that in the case of Hinckle, the path of an iconoclast is probably the most difficult road to take for a journalist:

“There’s a lot of people who were nowhere near as smart and talented as Warren, who had the presumption to become pundits. A lot of them make a good living now in Washington. I think Warren can beat ’em cold as a reporter, as a writer, as a thinker…Surviving in this life as an interesting person—doing interesting things—is not easy.”

“He needs that story,” says Bob Callahan. “That’s his addiction. The idea of something quiet, or any kind of spiritual life, the quiet life—Hinckle would laugh in your face. No philosopher king for Warren. He’s the last of his kind.”

Some would like to see Hinckle return to his sense of righteous indignation.

“He’s a muckraker,” insists the Examiner’s Bronstein. “He was passionate about going after things, and exposing things in his own inimitable way. But if you’re the booster for the establishment of San Francisco—I don’t care if it’s somebody as interesting and entertaining and colorful as Willie—you can’t engage in what you do best, which is muckraking.”

But Hinckle’s legendary style of fast and loose with the facts, creating his love-it-or-leave-it reputation with readers, is beginning to worry longtime friend Jim Wood, food critic at the Examiner:

“He’s done something recently that’s extremely troubling. I don’t know why he did it. I don’t understand it.”

Wood refers to a lunchtime crowd at the M&M, a newspaper bar on the corner of Fifth and Howard. Three weeks ago, a huddle convened of Chronicle and Examiner reporters, including Wood and Maitland Zane. All were discussing Hinckle’s recent column in the Independent about Chinatown activist Rose Pak. Hinckle had listed a few observations about her character flaws, then wrote:

“I raise these points as a person who genuinely, personally, likes Rose Pak. She swears and drinks and that is my type of person.”

The journalist beehive was completely baffled.

“She’s a non-drinker,” says Zane with the air of authority.

“It’s not like she’s a recovering alcoholic—she just doesn’t drink,” says Wood, a puzzled tone in his voice. “She’s never drunk. I thought that was the weirdest thing.”

Quentin Kopp is still on the line, tooling down I-80, talking about his lifelong friend Warren Hinckle.

“He has the most verve, the most imagination. He’s also fearless. It’s a wonder he hasn’t been whacked on defamation.” The senator pauses, then adds wryly, “Maybe because everyone figures, ‘Ah, who the hell pays attention to Hinckle?’ That could be, too.”

It was such a pleasure to read this again. Such a masterpiece! I'll never forget seeing one of our Examiner city editors, red-faced with irritation, having to pick up Bentley's poop from the carpet. Those were the days! xx Jane (fellow freeloader)

What a joyful stroll down memory lane. As a retired muni driver and devotee of Hinckle it was such a pleasure to revisit so much. I’d forgotten he married Cheever. I still have copies of “Frisco,” “Argonaut,” and even an old “Ramparts,” among other memorable screeds. Again to echo Pia, great profile!!!😎