Death Is Shakin’ on Shakedown Street

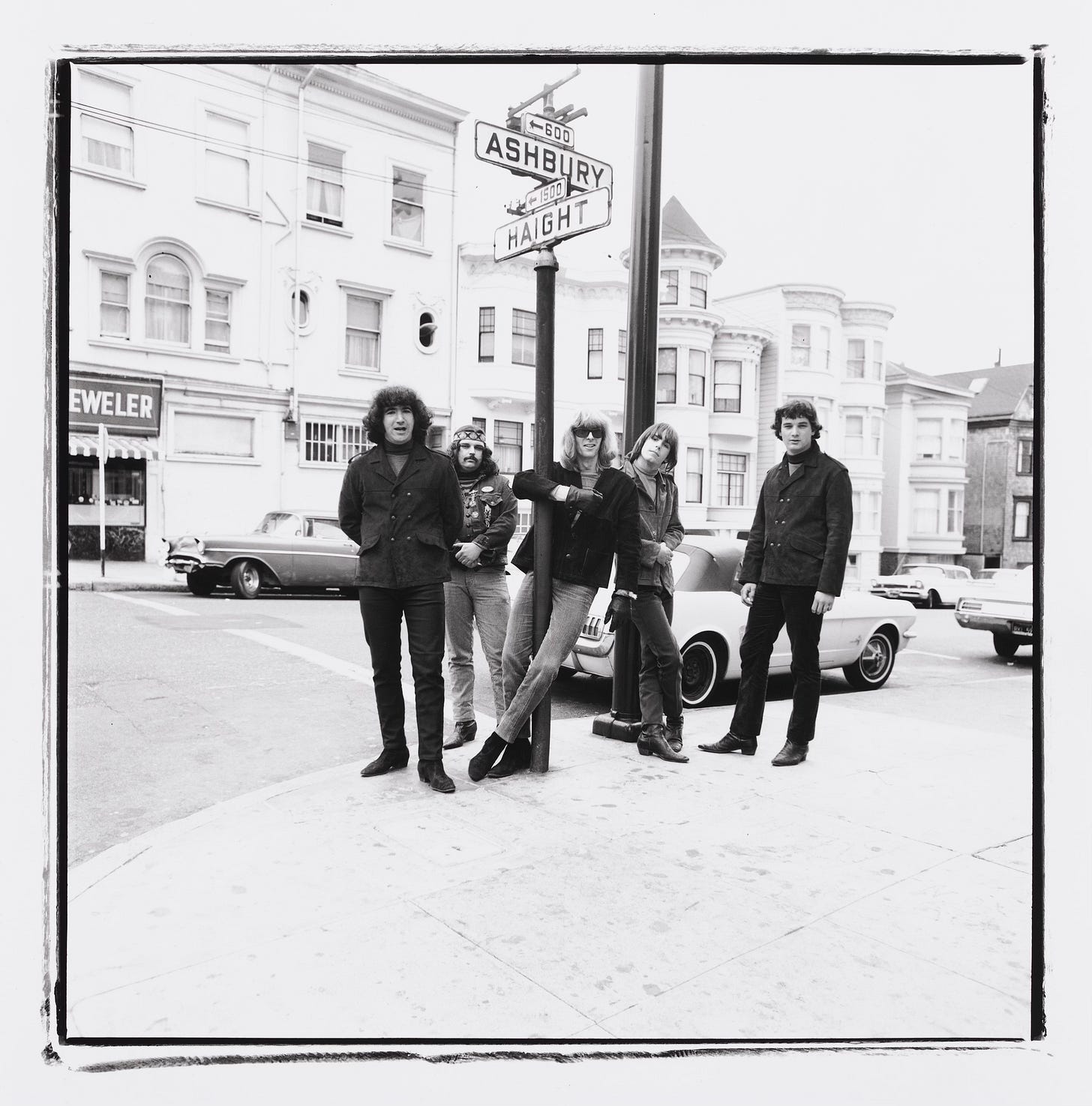

The Haight-Ashbury district, on the night Jerry Garcia died

I saw the Grateful Dead once, at a basketball stadium in Eugene, Oregon. I don’t have clear memories of the show. There was a woman at least eight months pregnant, dancing furiously next to me. Probably 200 drummers playing in the lobby. Ken Kesey came out onstage pulling a wagon painted with Day-Glo colors, and he took out mallets and began playing it like an instrument. The one true moment that stands out, is that every single person inside the venue was glued to Jerry Garcia’s guitar solos. It was a weirdly magnetic bond I’d never seen before. Of course, this was the Dead and everyone was high AF. But still compelling. After he finished each solo, the wave of zonked-out psychedelic energy flowed all the way to the back of the venue. Ancient and tribal. Nothing like it. I think of Garcia occasionally, perhaps because just up the road from my house is the rehab center where he died. If people would like to hear the real thing, or a few band members left of the real thing, Dead and Company is performing at the Sphere in Las Vegas until August 10. Jerry Garcia died on August 9, 1995, and as soon as I heard the news, I ran up to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood to check out the mayhem. This was originally published in SF Weekly.

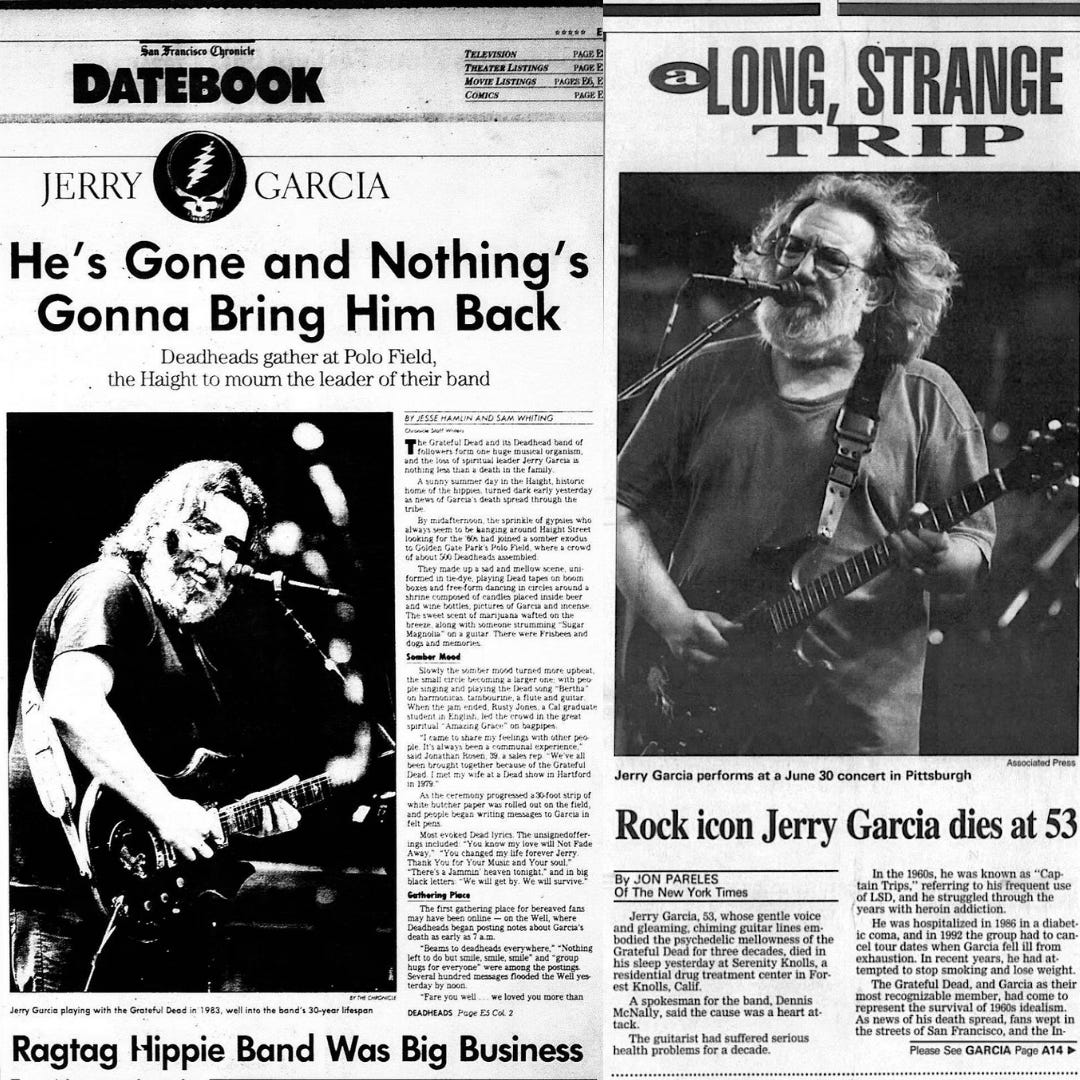

It’s late afternoon on the sardine-packed corner of Haight and Ashbury, approximately ten hours after Jerry Garcia’s corpse was found in a rehab center, dead of “natural causes.” All day long it’s been Garcia-mania. Radio stations are filled with music by the Dead, the WELL and AOL are clogged to capacity with Deadhead discussions in chat rooms and bulletin boards. Fans are furiously downloading Garcia snippets from audio and video libraries. Across the country, rallies are amassing in city parks. And in the upper Haight, police are busy pushing back foot traffic so buses can still go down the street. It’s chaos. Music blasts from apartment windows, interviews with Jerry waft from passing cars. Jostling for space with Deadheads, the homeless, curious tourists, 9-to-5ers coming home from work, and greedy journalists, is poor Karl Sonkin, reporter from NBC’s KRON-TV Channel 4, responding to the comments in his earpiece:

“Yes, Carl, I need to talk to Glenn RIGHT NOW. Don’t put me on hold…I will—FUCK!…I’m gonna talk to Glenn—”

Sonkin’s cameraman tries to be helpful. “There’s another phone—”

“Please…please…” mutters Sonkin. The cameraman backs off.

The pressure is mounting. News organizations across the planet are having Garcia-size heart attacks themselves, hunting down file photos and footage, shaping deadline stories with teasers that will surely say, “Long, Strange Trip Finally Over,” or perhaps the more tongue-in-cheek “We Will Survive—Not.” Panicked hacks are typing leads like “Living on reds, vitamin C, and cocaine finally took its toll on this icon of a counterculture…”

Every television station outside the Bay Area wants a video bite on the death of Garcia. Since there are no other local camera crews here, Sonkin is their whipping boy by default, providing live remotes for stations from San Jose to Seattle. In stark contrast, CNN’s camera crew stands calmly ten feet away, the blue-blazered reporter’s voice perfectly modulated as he goes live with his single report:

“Folks come here to sing his songs, dance to his music…This city takes its music and its heroes seriously.”

As if on command, the Haight struts its full plumage for Ted Turner’s camera. People are dancing to drums, black gauze hangs from the familiar Haight/Ashbury corner clock, candles are lit, dueling shrines appear on opposite corners. Except for the bustling Ben & Jerry’s ice cream shop, it could be 1968.

“COME ON!” snaps Sonkin suddenly. “When are we going to KING? And then what do we do? Who else? Don’s been telling me this shit that I’ve got a 5:30! And THEN an IFB?”

Sonkin’s cameraman leans over to a burly bodyguard hired by KRON for the afternoon. “That’s just the way he is, man. Very mercurial.”

A girl with a shirt that says “Smile, smile, smile” comes up to Sonkin and puts a little yellow bear sticker on his lapel. Sonkin grins and thanks her. When she tries to do it to the CNN reporter, he brusquely waves her off.

Three tourists from Israel crowd around a makeshift shrine on one of the street corners: a pile of Garcia photos, incense, and flowers. A slit-eyed girl in a blue stocking cap and worn backpack sits on the pavement scrawling a note on a piece of scrap paper:

Thank you for a real good time. R.I.P. Jerry Garcia. We Love You.

Merlin

Grizzly Bear

Ian

Marlene

The girl lifts up her pen, looks around, and slurs, “Who else?”

Finding no takers, she signs it “Love, Feather,” and shoves it with her foot into the midst of the pile.

A drum circle of 20 or so hippies forms across the street in front of a vintage clothing store. The collective body odor is beginning to approach the stench of an undrained bayou. Somebody keeps time with the beat by hitting a broken Mickeys bottle with his car keys. A punk girl runs by and yells, “You’re all going to kill yourselves for Jerry.” The hippies hear it but pay no attention. She doesn’t know. She’s never sat in the Phil Zone.

“I’m not gonna have echoes in my ear, am I?” Sonkin tries to remain calm, talking to two people simultaneously. “Hello, Seattle? We’re gonna start on the Ashbury side. Who am I talking to? Dennis? Dennis, don’t panic. We’re about to change batteries.”

Sonkin is pumped with adrenalin. He turns to the crowd and asks nobody in particular: “Is the ice cream good? The Cherry Garcia? Kind of a body-blood type thing?”

The crowd groans. Sonkin doesn’t care. He needs to kill time, and keeps babbling. “It’s a different era when you see T-shirts that say Brooks Brothers.”

“Easy there,” says a young crew-cut with a Brooks Brothers T-shirt. “It takes all kinds.”

Two guys in flannel examine Dead lyrics that someone has chalked on the sidewalk.

“It’s about love,” offers one.

“It’s about weed,” corrects his companion. “Weed and LSD.”

The CNN crew finishes up, and the cameraman says to the reporter, “Nice job, Greg. You, Fred, and Kevin can go back.”

Sonkin, however, is stuck waiting for instructions. He’s already done a zillion 15-second bites, but the gaping maw of news could be still hungry for more.

By now an obvious acid vibe is beginning to kick in, as Deadheads begin coming on to their doses, preparing for an inevitable all-night vigil in the park. The mood is extremely stoned and disjointed. Two girls half his age barrage Sonkin with questions about his life.

“I’m actually from Chicago,” he replies. “I’ve lived here 20 years.”

One bleached-blonde with bare feet and a pierced lip looks at Sonkin’s blue blazer, forest-green Dockers, and shiny cordovan loafers and exclaims:

“You’re a little overdressed for the occasion.”

Sonkin shrugs.

His cameraman leans to me and whispers, “He was a personal friend of Bill Graham for many years.”

“Shoot the police first, then come back to me,” orders Sonkin. He pauses, listening to his earpiece. “Anything that anyone asks. I can’t think right now.”