Chile's $10 Billion Treasure

One American has spent over two decades digging up an island to find it

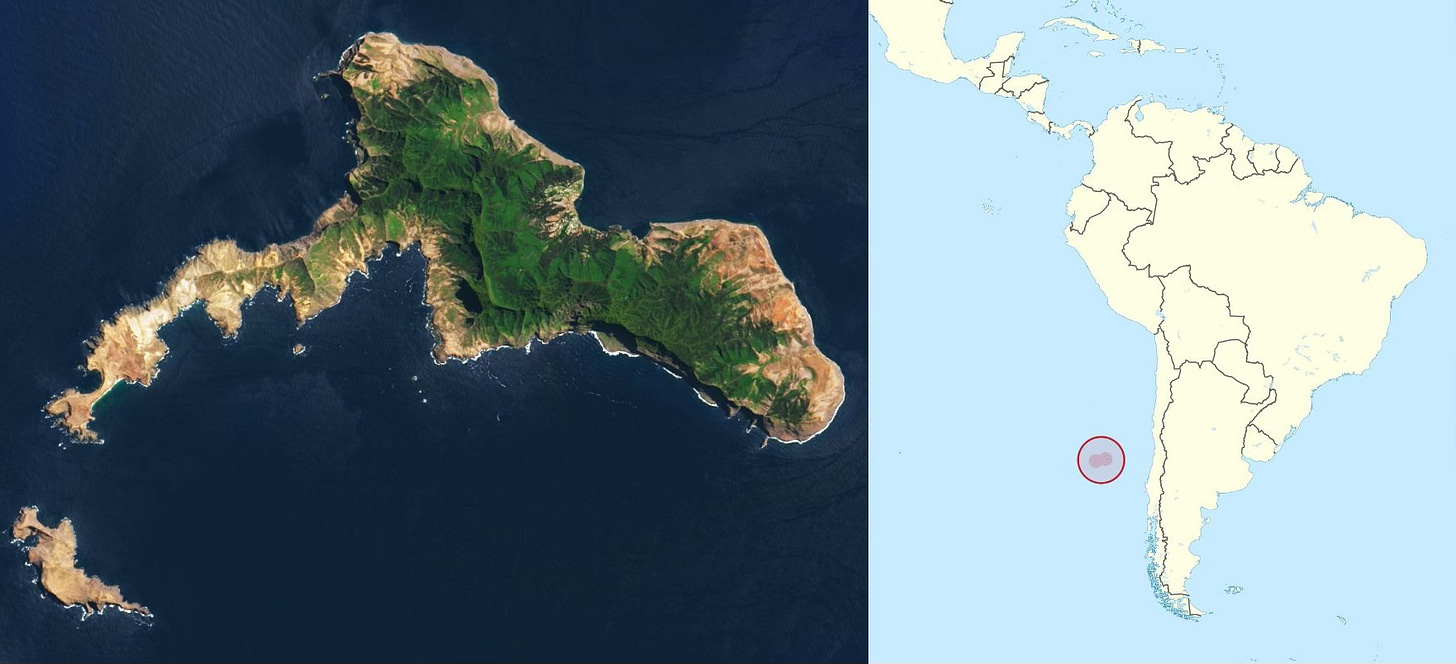

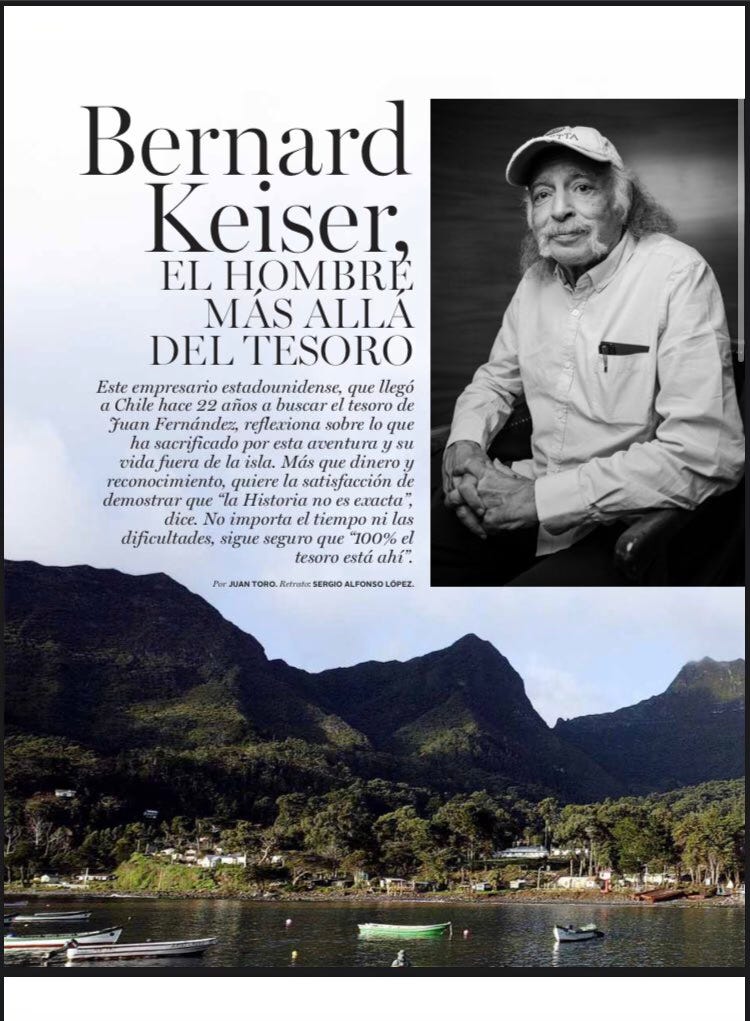

In the mid-2000s, I traveled to Robinson Crusoe Island, 400 miles off the coast of Chile, to do a story about an American treasure hunter. There’s something riveting about observing an obsessive person. Sure, it’s unsettling, and you begin to wonder how much of this trait you might also share. But you can’t completely turn away, you might miss something. In this case, the discovery of $10 billion in treasure, pilfered from Mexico and South America. As of 2019, the American is still digging on the same island, for the same treasure. A very different version first appeared in Maxim (yes, that magazine) in June 2006.

A fishing boat arrives at the pier of Robinson Crusoe Island, 400 miles off the coast of Chile. American treasure hunter Bernard Keiser climbs out of the boat and onto the pier, and is immediately pelted with questions from reporters. Cameras, microphones, tape recorders are shoved into his face. Your $10 billion treasure has just been found! By a high-tech robot! What do you have to say now, Gringo?

All of Chile is going ballistic over the possibility of the buried pirate booty. Islanders are already envisioning a new hospital and school. The mayor is demanding each resident should receive an equal share—$8 million apiece.

The American is aghast. For six years he’s made this journey to the tiny island, hunting for an 18th-century stash of gold. Each October he returns here to continue his excavations, in obscurity. But as of today, his anonymity is gone forever.

All the money he has spent. The months of research. The wrangling of government permits. Only to have the treasure stolen away by a little wheeled robot named Arturito. Everyone in Chile is laughing at him. Despite his doctor’s orders, Keiser starts smoking again.

Arturito was a four-wheeled, remote-controlled gizmo decorated with a rotating red light. Because the appliance resembled the Star Wars’ R2D2, it was thus nicknamed “Arturito,” or “little Arthur.” A ground-penetrating sensor was supposed to identify buried metals up to 50 meters. Its owner, Wagner Technologies, claimed previous successes: Arturito had located a cache of illegal weapons, and found the corpse of a missing businessman.

Within two days of arriving at Robinson Crusoe island, Arturito discovered three separate treasure locations. Media immediately fell in love with the cute robot that claimed the gold for Chile. There was no love for Keiser, the American. Reporters described him as “Gringo Loco,” and made fun of his remedial Spanish. Chile’s largest newpaper, El Mercurio, screamed the headline, “Bernard Keiser: ¿el gran perdedor?” (“The Great Loser?”). All without anyone so much as sticking a shovel into the dirt to verify the claim.

And then the cute robot story began to unravel. Scientific experts expressed doubts as to the robot’s claimed “atomic gamma rays” and “anti-plasma reactor” technology. Locals pointed out that Arturito’s locations, the jagged peaks of a mountain, were impossibly remote. Spanish sailors would never haul chests of gold up the steep slopes.

Wagner Technologies then suddenly announced it was forfeiting all rights to the treasure. Arturito’s inventor, a man named Manuel Salinas, gave a speech to a university physics class in Valparaiso, and was unable to explain how the robot even worked. The professor abruptly ended Salinas’ presentation, to a rousing ovation from students.

Within two weeks, the bogus Arturito was shamed into oblivion. Robinson Crusoe Island returned to its leisurely pre-robot pace. Fishermen continued trapping langostas. Tourists kept bird-watching and scuba diving. And Bernard Keiser went back to excavating. He’s not here for the lobster or the scuba. He knows in his heart, the treasure is still here.

He doesn’t want to talk about Arturito. But he can’t not talk about it. Because of Arturito, everyone now knows about him. He’s even listed in tourist guidebooks.

“It was ridiculous,” Keiser says evenly, somewhat exasperated at having to explain it all over again. “Is it logical that if this thing can find the treasure, and it can find anything, go 50 kilometers into the ground—wouldn’t somebody be using this? Wouldn’t they be patenting it? Wouldn’t they be selling it to all the mining companies in the world? All the Exxons, all the Shells? What are they doing here? The whole thing is absurd.”

Almost as absurd as the idea of an American selling off his business and moving to an isolated island, to spend six years digging for treasure. And not finding it.

Most people don’t bother hunting for treasure. The risk is too great, the odds too long. The obsession either pulses naturally within your DNA, or you experience a bizarre epiphany and realize your true calling. In the case of 56-year-old Bernard Keiser, it is both.

Raised in Chicago by Dutch-Jewish immigrant parents, little Bernie had in many ways a typical Midwest childhood. He grew his hair long, listened to Chicago blues music, drove muscle cars. While attending college in Jacksonville, Florida, he noticed the ongoing efforts of legendary treasure hunter Mel Fisher.

In Florida, you couldn’t help but hear about Fisher. In the 1960s, the former scuba instructor was among the team to first discover the Spanish Plate Fleet, a group of 12 ships which sunk in a 1715 hurricane off the Florida coast. Fisher’s expeditions yielded millions of dollars in gold, and made him internationally famous. Like many in Florida, Bernard Keiser read treasure books, scuba-dived the waters, picked up coins on the beaches.

It was a youthful and short-lived obsession. Bernie returned to Chicago, and with a loan from his parents, co-founded a textiles company, Architex International. It wasn’t much of a stretch from the family business—his father sold drapes.

The timing was perfect, an ambitious son of immigrants, coinciding with the growth of America’s new office cubicle culture. Businesses were adding more employees, and demand was high for fabric-covered furniture and room dividers. Architex pushed its textiles to companies like Steelcase, and NASA bought material for its space suits. By the 1980s, the company employed over 200 workers, and operated a 50,000-square-foot warehouse.

The money was good, and Keiser worked hard for it. So he bought some toys. He owned a sailboat. He collected vintage cars. He and his wife raised two sons. But he never forgot Mel Fisher.

And then one day in 1996, he turned on the television and was captivated by a program on the Learning Channel, a documentary called The Hunt For Amazing Treasures. One treasure in particular caught his eye—the rumored stash of Captain General Don Juan Esteban de Ubilla y Echeverria.

In the early 18th century, the Spanish commander was in charge of ferrying booty from Mexican and South American colonies back to Spain. Along the route, Ubilla had supposedly stolen and hidden some of his cargo on a remote Chilean island, at the time called Más a Tierra.

Keiser watched as the program revealed copies of three letters, which described Ubilla’s treasure and its location. Two letters had turned up in England, and one was found in Chile. This last letter Keiser was most curious about.

“Something hit me, very funny about the document,” he remembers. “The words that were used. I thought, wait a minute. A Chilean does not write Old English. It’s different phrasing, different words. Very difficult to write.”

Keiser taped the program on his VCR, and watched it again and again. There was something about the document. “It had historical facts that only a historian would know. Only someone from that time period would have known how to write it.”

He traveled to England, researching the letters in libraries, maritime logs, public records, newspaper archives. After six months of rummaging, he returned home to Chicago, his brain churning with facts and questions. He was in too deep. There was only one thing to do. In late 1996 he came to Robinson Crusoe Island.

A fishing boat takes me to the rocky coast of Puerto Ingles (“English Port”), on the north side of the island. Since 1999, this small valley is where Keiser has been digging for Ubilla’s treasure. I don’t know what he looks like, but Americans are not hard to find. Only 600 people live here.

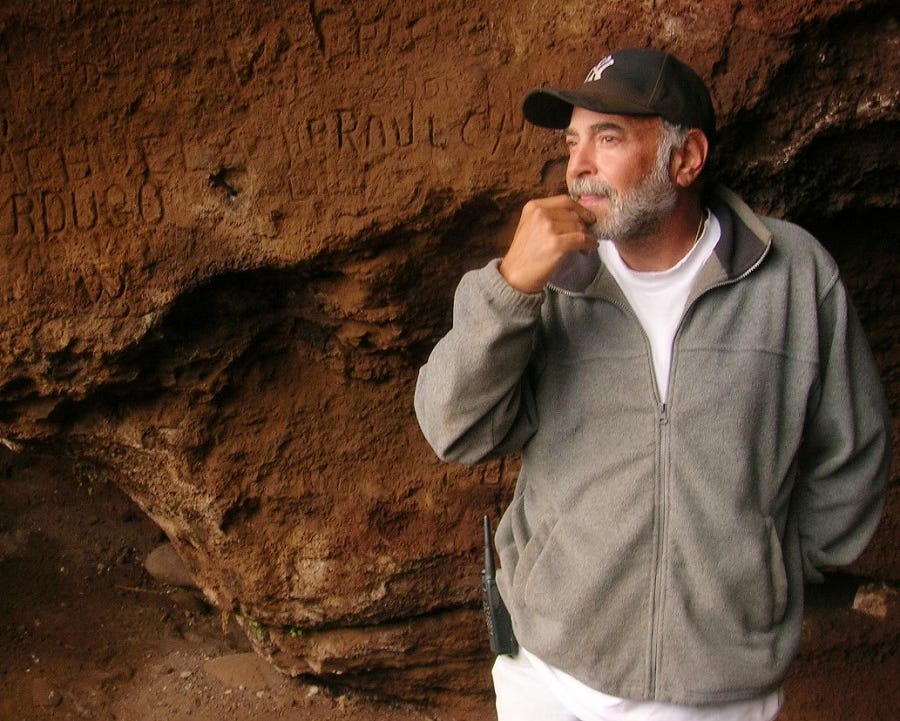

I walk past a group of Chilean excavators, working with hand trowels, and come to Selkirk’s Cave, a jagged hole in the hillside about 10 feet high. This cave was named for Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish sailor who was marooned on the island from 1704-1709. His experience formed the basis for Daniel Defoe’s classic novel Robinson Crusoe.

(In 1968, the Chilean government renamed Más a Tierra to Robinson Crusoe Island, to promote tourism. It certainly wasn’t to promote historical accuracy. The fictional Crusoe character was actually stranded in the Caribbean instead of the Pacific. While Crusoe had his sidekick Man Friday, Selkirk was alone. And a neighboring island, Más Afuera, was renamed Alejandro Selkirk Island, even though Selkirk never set foot there.)

A small bearded man sits inside the cave on a portable stool, sipping instant coffee. Bernard Keiser wears a yellow raincoat and safari hat with one side pinned up. His jeans are grubby with soil. A Kent cigarette lingers in his hand.

Is this Selkirk’s Cave, I ask.

“Well, it’s called Selkirk’s Cave,” he smiles. “But he never lived here. They just say that, for the tourists.”

We start chatting, and when the subject of Arturito comes up, Keiser sighs and shakes his head.

“Name me one high-tech innovation that came from Chile—there’s none,” he says in a flat Chicago accent. “I told them, ‘I don’t want to have anything to do with that company, that machine, with the little light on top.’ It didn’t pertain to anything here at all.”

We examine the walls of the cave, covered with names and dates and odd petroglyphs. This room is where Keiser first began his research, and he believes the treasure was once hidden right here, beneath our feet. He points out each carving. The name “ANSON.” A carving of a rose. An “AB” surrounded by a diamond. An S-shaped design, with three holes.

“Man has a reason for doing everything he does,” he tells me. “Especially in the olden days. When you see something, there must have been a reason for it.”

As he explains what each means, a whopper of a story begins to fall together. Some of it might be true, some is conjecture and guesswork, and weeks later, some details still don't make sense. But an incredible tale nevertheless. Based on several years of research in England and Spain, his theory goes something like this:

In 1713 and 1714, Ubilla sailed to the island and stashed six to eight million pesos’ worth of treasures. He carved an S-shaped map of South America into the cave wall, and also the diamond shape, which was stamped into silver bars to denote purification. To hide his theft, Ubilla doctored the ship’s manifest, low-balling the total. But before Ubilla could return to retrieve it, he was killed in the Florida Plate Fleet storm.

Nearly 50 years later, on orders from English Lord High Admiral George Anson, sailor Cornelius Webb left Britain on a secret mission—to bring back this Spanish treasure in the name of the crown. In 1761, Webb found Ubilla’s gold hidden inside a tunnel of volcanic rock. His men used black powder to blow out the side of the chamber (creating what is now Selkirk’s Cave), and hauled all of it onto the ship. Webb carved the name “ANSON” into the wall, and added a rose shape, because the treasure contained a unique, jewel-encrusted rose.

The ship set out for England, encountered a storm, broke a mast, and was forced to return to the island. Webb’s men off-loaded the treasure, and reburied it back at Puerto Ingles (Keiser believes this new location is very near the cave). Webb then sailed to Valparaiso, the nearest Chilean port, for repairs. When alerted to a secret mutiny brewing, he blew up his own ship, killing all the crew members, and rowed away on a small boat. He was the only survivor.

Webb wrote two letters to Lord Anson, describing that he found the Ubilla treasure—including 864 bags of gold, 200 bars of gold, 21 barrels of precious stones and jewelry, and 160 chests of gold and silver coins—and that he reburied it. The second letter included the code words “yellow stone” and “Dschubba” (ancient name of a star in the Scorpio constellation). But Anson died before receiving them, and Webb died the following year.

The Ubilla story—and treasure, if there is any—sat dormant until 1950, when the letters came into the hands of Luis Cousiño, at that time the richest man in Chile. Cousiño decided to hunt for the treasure himself. He anchored his yacht in the island harbor, and excavated a portion of the hillside at San Juan Bautiste, the only village. Finding nothing, Cousiño gave up. The letters were passed down to his ex-daughter-in-law, Maria Beéche, who still lives on the island today.

Decades later, Beéche was interviewed for the buried treasure documentary. Keiser met with Beéche, and she shared her letters in exchange for a percentage of any treasure. He spent the next two years securing excavation permits from the Chilean government, and started digging in 1999. He’s coy about costs, but some say he’s spent millions of his own money.

Keiser gestures at the walls. “It took years of looking, trying to figure this all out. What it meant. So knowing this, all of a sudden—shit, it’s coming together.”

He lights another cigarette. “I think there isn’t anything more I could find. There’s only so much that was written. Like a detective, you can only go so far.”

We walk around the valley, and he indicates spots that have been excavated, where he’s planning to dig next. He points to a hillside of peculiar yellow rocks. This is apparently the “yellow stone” and “scorpion” mentioned in a letter. I squint, but I can’t see a scorpion. The crew dug up this area previously, and this year is going back in and widening the dig. They’ve found many artifacts that date from the time of Ubilla. But still no treasure.

Few in Chile believe Keiser’s story. The media is against him. He fired a crew of archeologists because they were too skeptical. The government, in his view, is also an enormous pain in the ass. Keiser is allowed to excavate only from October through the end of March. After the end of each season, he is required to replace all the dirt and replant the area. He can’t use any backhoes or pneumatic hammers—the work must be done with hand tools. If they’re unearthing a previously excavated area, only then are they allowed to use shovels.

But Keiser is thankful about one thing. He’s the only person with licensed permission to excavate on the island. Nobody else is going to find it. Maybe not even him.

I drop by Keiser’s room at his hosteria, to see some of his artifacts. On the door is a sign that reads, “Bienvenido, Bernard Keiser,” with a little cartoon of a treasure chest and pirate flag. Fox News blares loudly from a TV. There’s a bed, a closet and bathroom. This is Bernard Keiser’s life. During excavation season, he lives in this room, keeping in touch with family through email and phone calls. The rest of the year he lives in Santiago, processing the artifacts and having them analyzed.

We look at photos of Chinese porcelain fragments. A thermo-luminescence lab test determined them to be 880 years old. Other fragments date from the 1700s, pieces of bottles and ceramic vessels. As he says, it is very odd to find these specific items on such an obscure island.

It’s time for the big news. Keiser hands over a xeroxed page with drawings of various sailor buttons. It was common for sailors to change the designs of their buttons every few years. He points out a button design from 1715, the same that was found among the Plate Fleet in Florida. He now pulls out a circular tin and opens it. inside is a small metal button resting in a pile of dirt. It’s identical to the Plate Fleet button.

Keiser stabs at it with a finger. “Now how the fuck did that button get here on the island? It’s not just a button, it’s a very particular button. You just don’t find it anywhere. Finding something that exists in one other spot in the world—the odds are a zillion to one.” This is one of about 20 identical buttons, all found at the same location. His theory is that in 1713 and 1714, as Ubilla’s sailors were working hard to hide the treasure, the buttons popped off their jackets.

He shows me copies of the letters from Webb to Anson. Even if no treasure is ever found, it’s exciting to read a 300-year-old letter that lists $10 billion worth of gold and silver and jewels and porcelain.

But Chilean historians aren’t interested, he says. Neither are other treasure hunters. He’s pretty much alone. Does his family consider him Gringo Loco?

“They know me pretty well,” Keiser says. “They know I wouldn’t do something stupid. It’s well researched.”

I mention that all this must get frustrating, especially when he’s finding such specific artifacts.

“It’s very frustrating. Very emotional. You take in the criticisms. You have to be calm, do what you can do and that’s it. The one thing I know is that it’s there.”

“Don’t you want to blow up the whole mountain?” I ask.

“No,” he answers ruefully. “I’d like to, but I know I can’t.”

He has given himself no deadline, he adds. It’s a cumulative effect that keeps him going. Each button and sliver of ceramic connects to his theories. He enjoys the patience, the detective work. In a way, the process isn’t much different from running a textile company.

“Just like when you start a business,” he says. “Are you going to ask someone who is semi-successful, the first year, second year, third: ‘How long are you going to keep the business?’ As long as you’re making money, basically, as long as you’re on the right track—you keep on going. This is the same thing.”

I ask if he ever feels like giving up. “Mel Fisher didn’t give up,” he says quickly. For 14 years, Fisher searched for the wreck of one ship, the Atocha, off Key West. And he finally found it. To treasure hunters, Mel Fisher was a god.

“He passed over the wreck site a number of times, not thinking that it was anything unusual,” Keiser continues softly. “Every morning he would say, ‘Today’s the day.’ Those famous words, for 14 years. And it ended up one day he found the cannons. He found the silver, gold, strewn over the floor of the ocean. They’re still finding things today.”

Keiser replaces the papers back into a file. “The treasure’s here, we’ll see.”

The Chilean press has moved onto other stories. Mayor Leopoldo González Charpentier had at first envisioned a treasure theme park, even building a monument to Arturito. But like a true politician, he added that the island’s “greatest treasure is its people.”

Locals still laugh at Arturito. That was silly. There might be a treasure here, who knows, it’s a nice story. But when asked directly about Keiser, villagers start muttering to each other in Spanish, without translating. It’s a small community. Nobody wants to criticize too much.

On a boisterous night at the Village Daniel Defoe bar, a group of sailors are celebrating their recent voyage, in 30-knot winds, from Valparaiso. Out of six sailboats, two were forced to turn back, their crews vomiting in the rough seas. So of course the crews who survived the trip are flush with victory and mad with alcohol. Four rowdies are downing Pisco sours and pounding their fists on the bar, shouting in unison, “Juan Fernandez! Juan Fernandez!”

Keiser is the topic of discussion at a table of yachtistas. One of them relights his stubby Cohiba and leans into my face. “Bernard eez a nice guy,” he slurs loudly. “But I theenk, sometime? He believe too much, you know?”

A scant 100 meters down the dirt road, Bernard Keiser sits on the bed in his hosteria room, checking emails, as Bill O’Reilly’s voice erupts from the TV. He opens another pack of Kents. Maybe tomorrow will be the day.