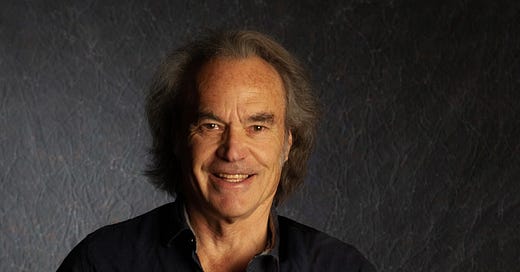

Charlie Winton: Every Night was Saturday Night

How to build a publishing empire, and still party with the Rolling Stones

This is a long one, so buckle in for the ride. I’ve known Charlie Winton from afar for many years. But not until we sat for an interview did I realize what an incredible story he’s lived.

Here’s the short version: Charlie Winton retired in 2016 after 40 years in the book business, as CEO of the Berkeley-based Publishers Group West distributor and publisher, taking it from two employees to over 500 at its peak. He now writes and records his own music.

Here’s the longer, more interesting version: Gore Vidal, Morgan Entrekin, Carroll & Graf, Wilson Pickett, Bobby Keys and the Rolling Stones, a Barnes & Noble fistfight with nightclub bouncers, a warehouse full of weed, environmental awareness, JFK assassination theories, hashish history, The Laughing Gas Handbook, Vivid porn studios, Amazon thug tactics, Morphine, Koko Taylor, Michelle Shocked, Rick Steves, Norman Mailer, Jim Harrison, Tom Tom Club, and Dee Dee Ramone.

Let’s just jump right in.

My mother and father’s roots are in Minneapolis. The family’s business was lumber. We lived in Sutter Creek, California from ’53 to ’56, we moved to British Columbia, another mill up there, my father was running the mills. Then he got transferred to Modesto. I went to boarding school in ’67, down in Monterey. My whole frame of reference of independence, self preservation, that comes from boarding school.

Was it a strict school, or was it more of a free-for-all?

The school went through a change in ’69, the headmaster got fired for embezzling. They brought in a progressive guy, and we were allowed to leave on the weekends. A friend of mine, his family had a place in Cupertino. We would leave campus on Friday night, take excursions up to the Fillmore, we would follow the shows as a teenager. It’s sort of the whole gateway thing. I started smoking dope when I was a sophomore. The next year I came back and it was like, hey you like marijuana? You’d love LSD. We started doing psychedelics when we were 16, because there was no real supervision for us.

So you enrolled at Stanford, what was that like?

I was an engineering major for one quarter, and I flunked calculus. I was immediately on academic probation. I wandered through various liberal arts. Stanford in the fall of ’71 was very political. I finally found the Communications department, that was the thing for me. Watching movies, studying television. Communications was so new at that point, it was the only major that you had to take a minor, so I minored in history. My wife Barbara and I met there. That’s where we started our relationship, which is still going. We lived together all through Stanford. Her family was so cool. Her mother was an artist, her father was a nuclear physicist. Ernie was amazing. He knew the Oppenheimer brothers. He worked with Edward Teller.

They weren’t lumber people from Minnesota.

Yeah. My father’s act of rebellion was to become a Republican.

And you met Morgan Entrekin at Stanford. He ended up publisher of Grove Atlantic, and one of the co-founders of Lit Hub. What did you think of him at the time?

We were ’75, he was in the class of ’77, he was a couple years behind. Morgan was kind of funny. He was a hippie, he had hair way down here. But he wore Brooks Brothers shirts, so he was kind of a Southern hippie. He’s from Nashville. An English major. He was very smart.

You graduated in ’75. What happened next?

I’m unemployed. The summer was horrendous, hard as hell to get a job. We went to L.A., came back to Palo Alto. I answered an ad to load a truck. That was a small textbook publisher, Page Ficklin, which would begat Publishers Group West the next year.

You got into this business because you took a gig to unload a truck?

Yeah. A four-day truck job. Once the truck was unloaded, they were like, “So, do you want a full-time job? You could be the warehouse guy.” I’d been trying to get a basic job for six months. Sounds cool. I could listen to the radio. I was a neophyte. I was just there.

So contrary to public opinion, there was no paved path from Stanford to the big high-paying job?

Not at all. I was the janitor at the trailer park at Stanford, so I was not that guy.

So basically I was working in the warehouse. Page Ficklin published textbooks. The owner, Jerry Ficklin, had a few books that were crossover, that could be sold in bookstores. In the summer of ’76, he wanted to do a road trip through the west, where we represented these books to bookstores in a more orthodox manner.

What other companies were doing this type of independent distribution?

Bookpeople was the thing. They started in Berkeley about ’71. They were really a wholesaler. They had the small presses, significantly more than anybody else. But they would also buy the hit books from Random House, whatever would fit the counterculture niche. And they were a co-op. But Bookpeople was passive. If you worked at a bookstore, you picked up the phone, you looked through the Bookpeople catalog, and you called them. In the ’70s, sales was kind of, sales. Like, that was The Man.

Far out, man. No pressure, dude.

No pressure, right! So our thing was, let’s call on them, and so we can advocate for the books.

You’re going against the grain of what was the business model at the time?

Exactly. So we did that. Jerry and I went around with a bunch of books in a VW van. I was the young wingman with long hair. We stayed with my friends, and his family. We would go to mostly colleges.

What were some of these books?

These were really marginal titles. Calculator Calculus. One of the publishers, Boyd & Fraser, from San Francisco, had the first environmental history book, called American Environmental History: The Exploitation and Conservation of Natural Resources. That could cross over from being a textbook to a trade book.

We came back from this four-week journey around the west, and our trip was deemed successful enough to start essentially what was for 11, 12 months, a subsidiary of Page Ficklin, called Publishers Group West. Jerry and I started it together in December of 1976, with Steve Mandell, who was a rep, who lived in Palo Alto. Their thing was to persuade me to become a sales rep. My task was to move to Denver, and cover Denver, Chicago, Madison, Minneapolis, and parts in between.

So now you worked in publishing. And you were boots on the ground.

I was 23. I’m getting paid! I guess this is better than the warehouse. So I moved to Denver. I hit the bookstores. My best one was the environmental history title. I did that for six months.

PGW was going to fail the first year. Sales were like, 20 grand. It was nothing. Jerry wanted to move from Palo Alto to Pacific Grove. Linda the executive assistant, she didn’t want to move to Pacific Grove. So they go, well, Charlie, would you like to run Publishers Group West?

They handed it to you?

Yeah. Basically, it was gonna go out of business. There was no money coming in. I got a salary, I think it was $800 a month.

So you’re in charge of a company. Did you take a night class in business?

No. I just did it. I’ve always been really good at math. I think of myself as being a left brain-right brain person, somebody who is having to do math. My parlor trick in the office is that I can do math in my head, like percentages, and computations. I always felt that business is sort of the logic of algebra.

But the business was headed nowhere. Something drastic had to happen. What was next?

At the end of ’77, we had made it through the first year. I enjoyed living in Monterey. I hired the wife of a military guy from Fort Ord, who would come in in the morning and type orders. I would do the business part in the morning, and I would pack the books in the afternoon. But in order to move forward, to make up the money that was lost, the company was spun out of Page Ficklin to become its own company. Bill Hearst and Steve Mandell and I each put in 1800 dollars. Bill brought in And/Or Press. That’s when we got the drug books.

The late-’70s counterculture print media had really solidified by this time. There was Rolling Stone, Whole Earth Catalog, High Times, CoEvolution Quarterly. You were now distributing titles from the Bay Area publisher And/Or, which was known for their books about drugs. What were some of the biggest sellers?

Marijuana Grower’s Guide, Ed Rosenthal. Mushroom guides. The Great Books of Hashish. Eventually they did The Holistic Health Handbook. Ray Regiert with Hidden Hawaii was one of their books. And/Or, they were almost like drug dealers, you couldn’t sign a contract with them, you had to buy them. Everyone else was on consignment. So I would drive up to Berkeley on the weekends and go to the And/Or warehouse over by Fantasy Studios, and pick up.

By ’78 or ’79, And/Or was probably at least 25% of our business. Our little trick was that Bill and Steve had this relationship with the regional managers of the Waldenbooks chain. Who understood that they could sell the shit out of the And/Or books to kids in shopping malls. So we would sell them under the table. Not through the home office. That was really what took the business off. And that year we kind of broke even. We sold about 150,000, probably 50,000 was And/Or.

Bill was repping this other company, Nolo Press, Bill held that back for one year, and the next year he threw that in, and that became another big thing. I wanted to move to the Bay Area, so I moved the business to Emeryville in the summer of ’79, and that’s when Randy and Mike both joined. Randy Fleming was a classmate and friend from Stanford. Mike Winton is my younger brother. We were the whole crew for the first few months.

Nolo was legal advice. And/Or was drug advice. It was the changing taste of books. People bought books on topics they were curious about, that they couldn’t find anywhere else.

Yeah, books as tools. How to do your own divorce, how to grow your own pot.

“These are the mushrooms that will make you sick.”

Exactly! Some of it was silly. The Laughing Gas Handbook, I don’t know if you needed a whole handbook for that.

This explains a lot of the DNA of the company. It didn’t find success from a catalog of literary fiction, or diet books. This was progressive, rowdy West Coast counterculture stuff.

The big moment for us was the ABA, as it was then, in Los Angeles in ’79. At that point we had enough of a presence. We were still extremely small, but what we were known for, what we emphasized, is that we paid the publishers on time. That was this huge thing. But in order to have the reps, we had to charge more. Bookpeople got books at 50% off on consignment. For us, it was 55. That five, ten percent net sales was what we paid the reps.

I had gone to the B. Dalton chain in ’77, they were like, “Why do we need you? We have Bookpeople.” By ’79 we’d developed a reputation that we were honest. I was learning the business on the fly. Baron Wolman, the photographer, had a small press called Squarebooks. The Blimp Book was the book that opened the B. Dalton account for us. It was a book about blimps. It was all his photography.

God that’s so weird. A book about dirigibles?

Yeah. B. Dalton said, “Oh, well, we’ll have to buy that.”

That is crazy. So at some point, you were very aware of the need to diversify. You became a publisher. Bookpeople and Small Press Distribution didn’t really have organized programs for publishing. So for a distributor, this is unorthodox.

We had more ambition. Carroll & Graf was our first exclusive publisher. Two Grove alumni, Kent Carroll and Herman Graf, started Carroll & Graf in ’83. They had fiction, but they also did erotica, they were doing some originals. Ultimately, they would publish The 25th Hour, they published The Revenant. Herman Graf was incredibly literate. He was a legend, he’d been with Barney Rosset in the early ’60s. He would say things like, “Are you confused by my facade of vulgarity?”

[laughter]

He’s still around. After they joined us in ’83, we went from a discount to a percentage of net billing, so we could sell other wholesalers. We had to convert all of our publishers to exclusive. That was a big two-year process in the mid-’80s.

I can imagine that was tricky, to tell publishers they could only use PGW as their distributor.

I can say we probably got 90 percent. We lost a couple of significant clients. By ’86, everybody was exclusive, except for Last Gasp and Heyday, who we grandfathered in for years beyond everybody else. Ron Turner and I, always good. Malcolm Margolin, he was a good guy. We made it work. But they weren’t a big part of our whole thing.

In ’89 it was our first huge moment. We started with 50 Simple Things You Can Do to Save the Earth (The Earthworks Group). It sold two million copies, and all of a sudden, everybody had to deal with us. For 50 Simple Things, Bookpeople even opened an account with us, which was kind of a full-circle moment.

Julie Bennett, our marketing director at the time, was a partner in 50 Simple Things. With the author John Javna. Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader was his other thing. It was a huge boon for us. But Julie was really instrumental in developing this book while she was working in our office. Kind of that gray area. Is she doing her job? We got the distribution. But at that point, we were like, we should be investing in publishing too. Because we’re bringing a lot to the table. Moon Publications was a top ten client of ours, and they were going to be sold. Within two years, we bought 25%, and within a year we bought control.

What other publishers came into your orbit?

Our persona in the business all through the ’80s was kind of scrappy. We were mostly known for the parties. We started doing more fiction in the late ’80s. Four Walls Eight Windows, Milkweed joined us, they heard they could really sell books.

You also did several books about the JFK assassination.

We had four bestsellers, including one of the books the Oliver Stone movie was based on. Crossfire, by Jim Marrs. Plausible Denial by Mark Lane. High Treason, and Best Evidence. It was a huge thing to have four bestsellers on the New York Times list, and it framed us in a different way, the outer edge of nonfiction.

The ’90s were kind of a boom era for independent publishing. So in 1992 you created a sister company, Avalon Publishing Group, and you were Chairman and CEO of both Avalon and PGW.

Yeah. Both owned by the same Publishers Group Inc. As we started to build out PGW, we went from $2 million to $4 million to $8 million. 50 Simple Things took us from $20 million to $40 million. From 1987 to 1994, we went from a $10 million to $70 million company, and started Avalon as well. By the mid-’90s, in terms of Ingram, Barnes & Nobles, the Borders, and larger indie bookstores, we were a top ten vendor. And we were respected because we had books that sold, and we did business, and we were organized.

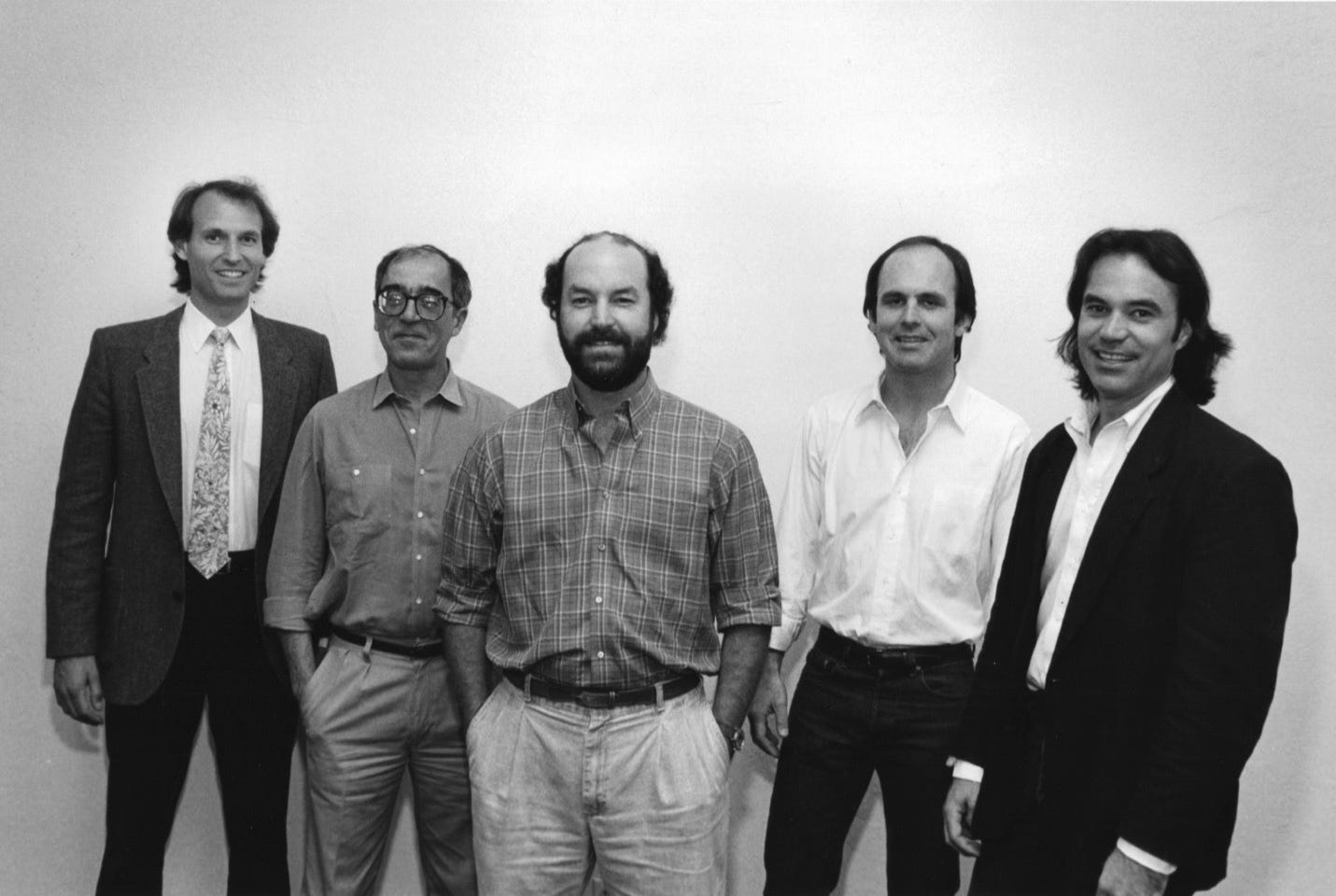

1989, PGW Board of Directors, PGW office, Emeryville, L to R: Steve Mandell, Bill Hurst, Mike Winton, Randy Fleming, Charlie Winton

One of my favorite aspects of our journey is that none of us were even close to MBAs. I was Communications, Randy was English, and Mike studied Biology at Cal. What’s amazing is that it’s still going. PGW was and is a safe space for publishers and independent-minded people, operating outside the corporate environment. You can operate outside the norm yet be inside the marketplace.

We were opportunistic. Things would come up. Publishers talk to one another. I ended up acquiring about a dozen companies over that ten-year period. We were in control of our own editorial, which was a positive from a creative point of view, and we shaped what we were doing more intentionally. And if we’re getting a 300,000 square-foot warehouse in Hayward, we know that there’s going to be x amount of dollars, through-put, from our own publishing.

This was around the time when you partnered with Grove/Atlantic.

We had admired Grove, because of Carroll & Graf. Henry Miller, all of that. Morgan Entrekin had been working with Sanyika Shakur, aka Kody Scott, on that book Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member. He was flying back, we met out at SFO, we went to some restaurant a mile out from the airport. We just said, we should work together. That could be really cool. Morgan could be a premium client for us, and he would have someone to really lean in and be supportive. So we had to negotiate. Which was kind of an interesting exercise, negotiating a contract with your friend. But it worked out amazingly well.

They joined us at the end of ’93. That was a big moment for PGW because it elevated what the list was, in terms of literature and backlist. It had been a big fight to get accepted by the mainstream booksellers. That was breaking down the final barrier, combining with Grove. Morgan is a fabulous publisher. He’s a super cool running mate. It was a total blast. We had great success, publishing-wise. Cold Mountain, Norman Mailer. They were about 10% of our revenue.

As the late ’90s came along, we had a more evolved strategy about what we were doing. Avalon was sort of the strategic move, it was also very much a creature of opportunity. So when we created Avalon Travel, it was like, hey, we can buy Foghorn, and we can buy John Muir and Rick Steves, and then we have a powerhouse company.

So in the early 2000s, the company looked like this. PGW was now among the top ten distributors to bookstores in the U.S., with offices in Berkeley, New York, Seattle, Reno and Toronto. And the imprints owned by Avalon were: Avalon Travel Publishing (including John Muir Publications, Moon Travel and Foghorn Outdoors), Carroll & Graf Publishers, Thunder’s Mouth Press, Nation Books, Marlowe & Company, Seal Press, Shoemaker & Hoard, and Blue Moon Books.

Avalon was PGW’s largest publishing client at this point, and represented approximately 25% of net sales.

And your largest and most important clients for PGW at this time were Avalon, Grove/Atlantic, New World Library, Taunton Press, Conari Press, and Backbeat Books, among others.

The first four collectively represented about 50% of net sales.

But you also had a very cool list of smaller clients, like Arena Editions, Black Classic Press, Canongate, Cleis Press, Feral House, Granta Books, Seven Stories Press, and Soft Skull.

Right. Those brought extra editorial zest to the overall list, and were a big part of our appeal to the booksellers.

I mean, this whole thing was huge. So in 2002, the Litquake festival had rebooted in San Francisco, with our new name. We gathered a bunch of people to serve on our planning committee, and one of our volunteers was Cynthia Wood. She was an employee at PGW.

She was my executive assistant, for all the executives.

Right. And she’s now an excellent photographer. She told us all of these stories about PGW. We weren’t that familiar. All we knew was that it was some book-related company in the East Bay. And Cynthia said, oh yeah, at PGW they had “Cocktail Fridays.”

Well at least, yeah!

That sounded like a lot more fun than the New York world I had seen. That comes from you, wanting to have a good time?

Yes. PGW’s relationship with substance, and fun, went all the way back to when we first moved to Emeryville, we had to sacrifice a large marijuana crop about three weeks early. The only place to bring them back was PGW.

Okay let’s stop for a second. We need to hear more about this. So this is in the late ’70s, and you were cultivators?

Well, informal. It’s hard to believe we even did this. We went out one morning to cut them. They’re like orange trees, they’re huge. Late September. It was a friend’s ranch, down in Woodside. And he wasn’t there, and somebody who was there said, “I think that’s the feds!” And everybody fled. So we went out two days later. Cut the plants out of there. We didn’t know what to do with them, so we hung them in the forest. Everybody just waited for about two weeks.

That’s so ridiculous!

And then Randy Fleming and I went out there with a truck, and nothing’s happened. We pulled them out of the forest, put ’em in the back of the pickup truck, covered it with a tarp, drove ’em to the PGW warehouse in Emeryville, and hang-dried them there. We had bags and bags and bags of weed. We had free weed in the PGW warehouse from ’79 to about ’83. We had so much. As we started hiring people, bookpackers to work in the warehouse, it became sort of an employee stash.

So what I’m hearing is that from the very beginning, the PGW company culture, there’s always been this sense of…frivolity?

Yes, frivolity, exactly. We were kind of operating that it should be fun.

In 1994 I went to the ABA for the first time, in Anaheim. For people who don’t know, this is the nation’s largest book convention. The depth and breadth of the industry, all jammed together on the exhibition floor. Everything from award-winning fiction, to deeply researched history titles, the kids’ stuff, the comics and manga, the large Christian market, on down to just utter stupidity. I remember a bald guy had printed up his own calendar—for bald guys. In the midst of all this was the PGW booth, buzzing with excitement. It was vast, all of your titles on display, and people were whispering about where the PGW party was going to be.

It was the Mayan Theater, downtown Los Angeles. Junior Walker and the Blasters, and Dave Alvin.

Yes! A fantastic show. It was surprising to go to a big rock show, where the audience is a bunch of book nerds. They’re out there getting loose and having the time of their life.

We saw ourselves as flag carriers. For sure. We enjoyed that role. By then, with the co-sponsors, we developed what we called the Den of Iniquity. At the Mayan, we probably hit the pinnacle. Where we would be together with the band, and all the publishers, and then after the party there would be an afterparty, in the Den of Iniquity. I remember Ron Turner coming into that party with two cases of Budweiser, a case on each shoulder.

Watching the PGW vibe, against the landscape of these more buttoned-down publishers and exhibitors, it made me so proud that the Fun Squad was from the Bay Area. How did that start?

The party thing. When the ABA was in San Francisco in ’85, our relationship with Bookpeople had evolved to “friendly competitors.” There wasn’t any animosity. They invited us to co-host the Small Press Party, as it was called then. Which was at the Gift Center. ZaSu Pitts Memorial Orchestra was the entertainment. That was unbelievable. There must have been over 3,000 people.

The next year we co-hosted at Tipitina’s in New Orleans, we had the Radiators. And that was smaller, but really fantastic. In ’88 we held a party in Anaheim, we had some local rock band, it was fine enough. One of the major publishers had a party the same night, and we were kind of scooped. The next year, in DC, we strategically made a decision to elevate what we were doing, so that we were the thing. And that was when Wilson Pickett was our band. Kilimanjaro was this reggae club in DC, and that was such a cool party.

Okay, so Paul Yamazaki, from City Lights, just told me this crazy story about this party, in 1989, where Wilson Pickett demanded to be paid up front in cash. You know what I’m talking about, right?

It was the first big party that we were doing on our own. We took on the responsibility of setting up the back line at the club. We should have hired somebody. My brother Mike and my assistant flew in, rented some music gear and drove back to the Kilimanjaro, got it all set up. They got back to the hotel at 6 pm, and I was like Mike, do you have the money? Fuck! We forgot to cash the check. They’re not going to play. We had to raise $8000 in two hours. It was crazy. Carroll & Graf was our largest publisher, they had both just gotten American Express cards, bless them, they could get four grand. Then the rest of us were scrambling around the Mayflower Hotel neighborhood. ATMs weren’t that common at the time.

So at the same time people were coming into the club to see the big Wilson Pickett show, PGW employees were running to ATM machines, using their personal bank cards?

Totally. We made it, but we had 400 20s. It looked like we had just finished a drug deal. I went backstage to meet Mrs. Pickett, because she did the money. She had this giant guy with her named Cabbage Patch, like 300 pounds. She counted it out, and it was a great show!

You’ve brought a list of some of the other PGW parties. Read some more of those.

Junior Walker, Buddy Guy played it in New York. Mickey Hart, in Hollywood. Eric Burdon. Michelle Shocked. Morphine in Chicago. Roomful of Blues.

Tell me about the Roomful of Blues year. This was 1990, when the convention was in Las Vegas.

Las Vegas, the Shark Club. Cool club. We’re negotiating to get the club, the guy says, “We require that our regulars come in at midnight.” It’s a private party, but okay. We had to be out of there by 1. At midnight, about two dozen women show up. “The regulars,” right? The party was hugely successful. Morgan and I are out in the back, celebrating the whole thing. I come back into the club, and it’s like, “Charlie! Charlie! The Barnes & Noble buyers have been beaten up!” What the fuck is going on? It’s 1 am, and now I got another situation to deal with. The Barnes & Noble guys, merchandise and marketing people, were totally shit-faced. The bouncers were putting the chairs back on the dance floor, refiguring the club. But the Barnes & Noble people were still dancing away. Somebody threw an elbow, that started it, and the bouncers just plugged them.

I got out to the hut in front of the club, and they had these four buyers, in a holding pen, waiting for the police to arrive. We spent an hour negotiating with the bouncers. “Couldn’t we have this just be a beat-up, without taking them to the station?” One guy had to go to the hospital. Herman Graf was just going apoplectic on the sidewalk, wanting to fight the bouncers. Three people were holding him back. It was like in the movies, “Let me at ’em.” He would have been 58 at the time. So after this, it was like oh fuck, man, Barnes & Noble. Are we going to hear from them? I would say for those folks it became a badge of honor. “Yeah, I was one of the guys who fought the bouncers.”

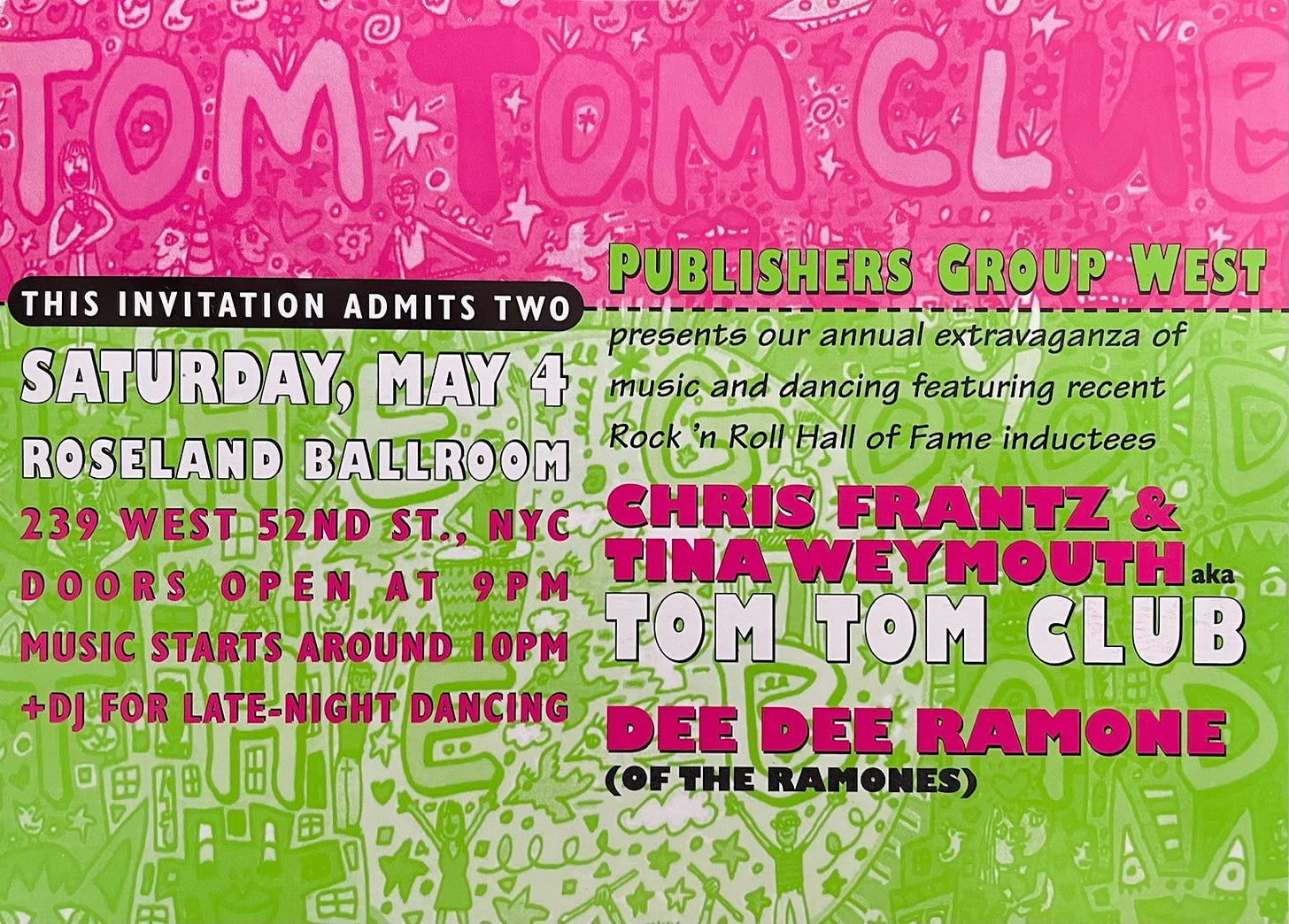

Damn, I missed out on all the good stuff. In 2002 I did go back to the ABA, which had become the BEA. This was in New York at the Javits Convention Center. I got a pass to your PGW party, which was super hip. It was at the Roseland Ballroom, with the Tom Tom Club and Dee Dee Ramone.

We published I think three of Dee Dee’s books. Thunder’s Mouth Press. We started to incorporate musicians we published into the thing. So Dee Dee was like, “Of course, for sure.” He had a band. Before the thing, I went down and was just chatting it up, and all of the Ramones were there, other than Joey. He played like six songs. I think they played one song with him. And then Dee Dee and I went out to watch the opening of the Tom Tom Club, and he turned to me with these big eyes and he said, “The Tom Tom Club. They’re so modern with their sound.”

Dee Dee died a month later of an overdose. This was one of his last shows. Could you tell he was going to be dead in a month?

No, I didn’t know. That was my one night hanging out with him. He was kind of a sweet man, is what I saw.

You’ve worked with so many authors on so many projects. Jim Harrison was a real character.

I just got along really well with him. His nickname for me was “El Don Carlo.” Sarah McLaughlin, not the singer, ran our PGW Canada office. A wonderful person. At the BEA Chicago, she says, “Michael Ondaatje would really want to meet Jim Harrison. Jim’s really comfortable around you, so I’m gonna set up a lunch at the Drake Hotel.” And we sat down, Sarah and I and Jim and Michael, and basically it was the Jim Harrison Show. Here’s Michael Ondaatje, a fairly accomplished writer, basically he got exactly what he wanted. The Jim Harrison Show, over cheeseburgers, right? It’s food, it’s literature, it’s poetry, it’s sex, you know, it’s off the cuff, and completely, oh my god.

What was the most fun book project you’ve worked on?

Bobby Keys was the most fun book. In 2011 I needed a personal shot in the arm, it was one of those rando things. Sometimes things come at you from left field, and they charge you up and turn you around and send you on a path.

The longtime saxophonist for the Rolling Stones, among many other acts. So you ended up publishing his memoir.

That started a four-year adventure. The first meeting, I flew down to L.A. I checked into a hotel, rolled up a fatty, wanted to establish my bona fide, that I was the best person in the publishing industry to do this. He said, “Whoa, you’re way different than I expected. I was thinking it would be a guy in a suit.”

So we’re toasty, I’m taking him out to dinner. We had a great evening, it was a fully robust affair. He knew Buddy Holly. He played with the Beatles, the Stones, and Elvis. Joe Cocker, and Mad Dogs and Englishmen. He had all these incredible stories about John Lennon.

The book title was the big thing. He wanted to call it Sideman. I had a title idea, a riff on a Stones lyric, but he didn’t want to go there. We were talking out on the sidewalk, and he says, “Well, you know, Charlie, every night’s a Saturday night, every day’s a Sunday.” That was the name of the book. Every Night’s a Saturday Night. We just evolved into a friendship. The book was published in 2012, it was well received and successful.

2012, Winton home, Berkeley, L to R: Charlie Winton, Bobby Keys, John Todd

So you mentioned that through Bobby, you got to meet the rest of the Stones?

When they restarted in 2012, the two opening shows of the tour were in Newark, and we were invited by Bobby. We’re staying at the Carlyle, we’re going to the afterparty, there’s Mick and Keith and Ronnie Wood, Lady Gaga, Johnny Depp. It’s fun, and funny. The whole thing is, you’re not a groupie. When you hang with these people, you have this relationship that is real, based on real stuff that you’re doing. You’re not just a fanboy or whatever.

Come on, it must have been just a little bit like, Oh my god it’s the fucking Stones?

Totally, totally. Exactly. You’re with Charlie Watts at the snacks table. We got to hang with Keith for half an hour before one of the shows. He was very relaxed, shooting the shit, talking about books. He wanted to know how they sounded!

What did you say? What could you say?

I said, “I thought you sounded great.”

When I was in New York, I was at the studio with Bobby. They had a band, Stone’s Throw, with Bobby and some of the members of the Stones. They were a hot band. We’re in the studio, we’re getting high, whatever. I’m out in the lobby and Mick Jagger walks in. Oh, wow. He’s practicing for an upcoming Saturday Night Live appearance. I said to Bobby, “Mick’s here.” He’s like, “I don’t want to talk to Mick.” So I’m hanging around. Mick’s manager sees me and asks, “Would you like to meet Mick?” We went into the studio, he had the music on, and he was doing his Mick Jagger aerobic moves in front of this giant mirror. Great hair, I want to tell you.

So let’s talk about Gore Vidal. You ended up publishing four books with him. What was that like?

We used to have these fantastic parties at Arianna Huffington’s house. Gore would show up. We had a bestseller with Vincent Bugliosi, The Betrayal of America, about Bush v. Gore. It was political pamphleteering. That’s what we were trying to do. The first was Bugliosi. The second was with Gore Vidal, Perpetual War For Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated. And his follow-up to that was Dreaming War: Blood For Oil And The Cheney-Bush Junta. Gore wanted to call it the United States of Amnesia.

That’s a really great title.

Not according to us! Shouldn’t we have more in the title? I was responsible for calling Gore and telling him we can’t go with that. I came up with the title, Dreaming of War. Now I gotta call Gore Vidal and have an editorial discussion about a title. The wisdom was to call in the early afternoon. After he’d had an early afternoon libation, he was a little more amenable. He was like, okay, get rid of the “of” and we’re set.

We also published Imperial America: Reflections On The United States Of Amnesia. So we did eventually get to use that line. And we published a collection of his short stories, Clouds and Eclipses.

When I was a little kid, Gore Vidal would be a frequent guest on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, always witty and super smart. He had that famous quote, “There are two things you never turn down: sex and appearing on television.” But he did seem to have a temper.

One night at Arianna’s, a benefit for The Nation, he was starting to get crabby. The people from The Nation asked me, “Can you get him out of here? Take him to dinner? Beverly Hills Hotel. He likes the Polo Lounge.” We loaded him in the car, got him over there, got him some food, and a drink or two, and everything worked out.

Gore would have these little gatherings at his house in L.A. The last time I saw him, he was sitting in a chair, almost like the intellectual Godfather. Someone would get to sit next to him for ten minutes. He wore a Simpsons high school letterman’s jacket, with Bart and Homer on it.

2002, Villa La Rondinaia, Revello, Italy, L to R: Charlie Winton, Gore Vidal, Barbara Winton, Howard Austen

Tell me about this photo with you and Gore Vidal.

The photo was taken in his place in Italy. Our family was there in 2002. i just gave him a call. “We’re gonna take a boat and go down the coast. I know you’re there, can we stop by?” Sure. What an amazing villa. So many mementos, lots of photos of the Kennedys, Paul Newman, all these people he’d met over the course of his life. The balcony, you’re looking over the Mediterranean from several hundred feet above the sea. Gore was obviously incredibly charming, super smart, a little prickly. Howard was his longtime companion. Howard was fantastic, he was a good mellow facilitator. We just hung out all afternoon, drank wine and talked about how horrible the Bush family is.

So you worked, briefly, with Lyle Stuart at Barricade Books.

Lyle was like the rough version of Barney Rosset. This big fat Jabba the Hut guy. Right before a marketing meeting, they had been on a nude cruise, and he brought the snapshots to the marketing meeting. You couldn’t see his junk, because he was sitting in a chair. But it was pretty gross. Not very appropriate.

We were distributing the Anarchist Cookbook, we sold a lot. But not a lot of stores called. It was controversial. Lyle had this new book from Palladin, one of the chapters was how to booby trap a house so you could kill a fireman. “You know, Lyle, I don’t think we can do that. I like firemen.” He got all umbraged, and within a year he was out of there.

Publishing isn’t always about award-winning literature or bestselling journalism. There’s always the underbelly. You had mentioned that you had a publishing deal with the Vivid adult film studio?

Neal Ortenberg ran our New York office, his stepmother was Liz Claiborne. He wanted to do books with Vivid. We got four porn stars to be the authors. Savannah Samson was one of them. I was in New York for a sales conference, which coincided with the launch of these four books with Vivid. Savannah had just starred in the remake of The Devil and Miss Jones. The movie people were having a launch party at a strip club, over on the West Side. The publicity person said, this would be a perfect opportunity to tag-team with some of the PGW crew. John Oakes, from Four Walls Eight Windows, he went to Princeton, button-down, definitely not someone who’s doing a lot of porn publishing. We went to this party. There’s free vodka. Everybody got free condoms and a free DVD of the new and the old Miss Jones. That is a party tchotchke. Someone said, “Oh, I’m a photographer.” Savannah was sitting behind a velvet rope. Mostly guys. She was having a meet and greet. It’s an oily situation. “Here’s the publisher and the CEO—we want to get a shot of you!” John and I got on the banquette, she grabbed my hand and put it on her upper thigh. The photo comes back the next day, and I saw it and said, “Burn it.”

So you and I saw each other again in 2013, when Litquake convened a mini-conference called “Digi.lit,” about digital publishing. You were on a panel, with the writer Isaac Fitzgerald as moderator. Jon Fine was representing Amazon. The Bay Area book culture is very feisty, very indie, very anti-Amazon. The panel began, and it was one of the most intense literary conversations I have ever witnessed, and certainly produced. The room was vibrating, waiting to see what would happen. At some point, the subject came up about how Amazon treats publishers. And you looked at him and said, “Well, you treat us like you’re a thug.” I’m paraphrasing.

I recall that. “You negotiate things like a thug.” I just felt like that was an opportunity. Because Amazon is this giant, it’s a double-edge nuclear weapon, it’s crazy. And somebody needed to say, you guys are really kind of fuckers. Sure, we can all embrace this customer-centric orientation, like we’re just going to be doing everything for the customer. Well, what about the people who are giving you the goods, for your customers? You have to treat them with some dignity and respect. You have such an infantile understanding of the dynamics of actually publishing a book.

The entire audience gasped. It was quite thrilling. Fine replied in the manner you’d expect, oh well, this is just, you know, he spun it. And poor Isaac, in the middle, was having a heart attack. I think he said, “Can’t we all just get along?” Now he’s a regular guest on The Today Show, discussing books.

Yeah, it’s funny to see how he’s evolved.

So you retired in 2016 from PGW, from Avalon, from everything.

Well, yeah. PGW sold in 2002, Avalon was sold in 2007, and Counterpoint was 2016. At the end of PGW, and Avalon, when they were sold, over 50 people were shareholders in the company. We had given out stock options. They’re still all there, they’ve been there for 30 years.

So the moment you signed the paper, what did you do?

The reality was, it took about eight or nine months of wind-down. But music was what I really wanted to do.

So you worked for 40 years, shipping books around the U.S., throwing parties, publishing books, dealing with authors, dealing with bookstores, dealing with employees, all of that stuff. And suddenly it just stopped.

Once I worked through it, it was like this huge relief. I’m kind of free. I think anybody who loves the engagement of things, it’s like okay, am I still gonna be engaged? You’re kind of losing your connections. How much of your connectivity, or your pertinence to the world, is connected to work?

At the height of it, you were talking, working, interacting with 100 people a day. And suddenly, you were interacting with...your wife?

And the cat. And my guitar. [laughter]

Very different way to go about your day.

I started to have more time to play music. I started these jam groups. Barbara was playing piano with us. And in the summer of 2017, I reconnected with this old friend, Dave Eakin. He said, you should come down to Monterey, and we’ll have a music weekend. So I sent him a bunch of covers, here’s 15 songs I can sing. Stones, Dylan, old-timey stuff. We did that for a couple hours, and he was like, “That song you wrote when you were down here last year? Let’s play that one.” It was like okay, cool. “Do you have any more?” I was like, hell yeah, I got a lot more. We played my tunes for the rest of the weekend. And for me, that was this great moment of coming out, a little bit.

Why didn’t you do that before?

You know, it was sort of one of those things. So much business. If you think, in 1999, 2000, I had 500 employees, you know. We had jam sessions all the time, in the warehouse, at the office, but again, what you’re doing is, “Hey, I’m the CEO so let’s play my songs!” So I started playing with other people, and then Joel Selvin, at some point, hooked me up with Scott Mathews. And that was the perfect person at the perfect time.

Scott Mathews is a giant in the music industry. His credits are insane. He’s recorded or performed with: The Beach Boys, Johnny Cash, Roseanne Cash, Eric Clapton, Elvis Costello, Ry Cooder, Jerry Garcia, Robert Cray, John Fogerty, George Harrison, John Lee Hooker, Booker T. Jones, Patti Labelle, Nick Lowe, Van Morrison, Aaron Neville, Roy Orbison, Bonnie Raitt, Keith Richards, Carlos Santana, Boz Scaggs, Ringo Starr, Barbra Streisand, and Neil Young. And now he’s producing you.

Part of the reason I went to Scott is that I needed to elevate who I’m playing with. From doing this for a couple years, I think there’s something here.

So you’ve done three albums with him. It’s very intuitive how he adds the music around what you’re doing. Some songs are acoustic rock, some are harder and faster, even a reggae-flavored beat. To anyone who knows you, it’s your singing voice that really leaps out.

2024, Charlie Winton, Eternal Light album cover

I always sang in that voice, but I didn’t know if it was too rough. And Scott was like, “No, that’s your voice. I believe that guy.”

It’s very believable, very authentic. And the lyrics you write are very positive. There’s themes of desire, love, angels, getting high. Were all these tunes written after your retirement?

Some songs were written a few years ago, some were written 15 years ago. Most of the tunes were written after 2016.

People in the publishing world have said to me, hey, have you heard Charlie’s music? It’s pretty good! Like, we’re not expecting someone from the publishing industry to have a voice like that, with such a professional studio sound. Why don’t you perform it live?

I think about it all the time. Scott said to me, “I can put a band together for you, it’d probably be 30-year-olds, who just want to play.” And that just seemed—it’s gotta feel good to me, and organic. I don’t want to be Roger McNamee, where I’m going out and hiring a bunch of people to play with me.

Right, Roger the tech investor. His band Moonalice, you could call it a ringer band. You know who else did that? Kermit Lynch, the winemaker. Hired professional players from Nashville. I understand about you wanting it to be organic, rather than…

Contrived. But I hear you, and many people have said that to me. Somebody said, “You gotta be able to play if somebody offers.” So, yeah. I’m trying to navigate life as a 71-year-old man. It has to feel like something I have to do.

You have two children. What do your kids think about this?

Jack’s a film editor. Jack and I play together, he can play. My daughter Kelly designed all the albums. She’s a designer, book covers and that sort of thing. Kelly just doesn’t want me to be too cringe-y, that’s her whole thing.

Do you approach your music from a publisher or editor brain? Are you looking at your songs and thinking, how am I going to market this, how many units can we sell? Or is the editor part of you going, yeah, but on track 7, maybe I could take another pass at that lyric? Do you have these conversations with yourself?

Sure, both. The creation process I for sure self-edit, and I pick at things word by word. The publishing part, that’s been equally fascinating for me. I had no plan for the first album at all, I just wanted to record the songs. It came out, I played it for Joel, and Joel sent it to other people. And I would hear, “What do you want to do? Do you want a contract?”

“So what’s your five-year plan?”

Yeah, exactly. That was always the question. I don’t know what I want. I wanted to record the songs. The whole process, in some weird way, there’s such an echo from the publishing business. It’s different, but also there’s lots of similarities not only in terms of the storytelling, but the product itself. So what does one do, if you’re me? And how do you try to advocate yourself? Within reason, without being stupid, or silly about it?

Or cringe-y, as your daughter said.

Cringe-y. I was gonna say. The first week in the studio with Scott, it was like, are you thinking about a stage name? I came back the next day and I said, the least shameful thing I can do is just be myself. You know?

I remember at literary events, you would often have a side conversation with your author. An extra sort of interaction, pep talk, career advice. So now you’re on the other side. Who’s doing that for you? Who’s saying, Hey Charlie, keep doing what you’re doing?

Selvin is a great supporter. Scott. Barbara, obviously is huge. Actually my big supporter, the guy I talk to all the time, is Bill Bentley.

Bill Bentley, he’s an old-school music executive, works with Neil Young. He organized the recent Lou Reed tribute album.

So Bill, we’re working on stuff. But low-key. We’ve become close as friends. He is providing that juice to me, that you’re talking about. And now I’m the artist.

You’re the artist. “Please don’t make direct eye contact with Charlie.”

[laughter] That’s what Scott said. “Oh, you’re the artist. What does the artist want?”

“Mr. Winton, what do you require backstage?”

Metamucil!

Love this Jack! I met Charlie back in the Argonaut days with my dad. PGW was our distributor.

What a fascinating profile. And here I thought ALA (American Library Association) parties were fun! Tame by comparison