Brief Dabbles with Science Fiction

And meeting real writers for the first time

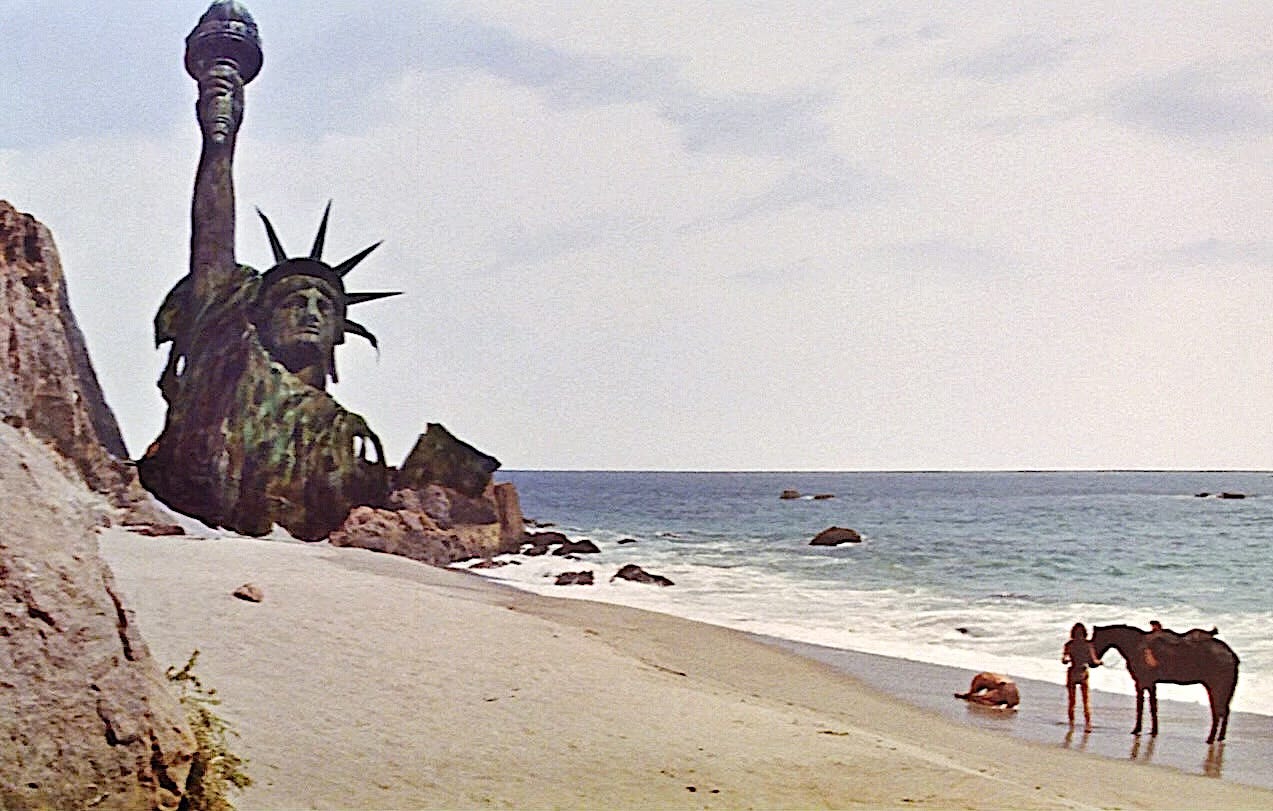

Iconic image from the 1968 version of Planet of the Apes, with Charlton Heston, Linda Harrison, and a horse.

The 60s-70s period of cinematic science fiction was a heady era which portrayed our future as a horrific testament to human neglect—The Omega Man, The Andromeda Strain, Soylent Green, Westworld, Rollerball. My friends and I gobbled them up like candy, because they were fun! The same with TV shows like The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery, both hosted by Rod “three-packs-a-day” Serling. There was a bunch of feel-good sci-fi on TV during this time, but it didn’t hold my interest. Lost in Space, Star Trek? Kind of wimpy. I guess I was a pessimistic little kid, wanting to be reassured that humanity was doomed.

The Platinum Level of sci-fi bleakness was of course the Planet of the Apes films, based on a novel by French spy Pierre Boulle. There were five total at the time, and my friend Karl and I referred to them by single titles: Planet, Beneath, Escape, Conquest, and Battle. (“That scene where they worshipped the atom bomb, that was Escape?” “No, that was Beneath.”) When our local movie theater screened all five in one night, of course we had to see them on the big screen, and after a ten-hour barrage of Ape Future, we walked out into the darkened streets, crouching and hopping like monkeys.

And then I started high school.

Geometry class was an exercise in futility, a continual struggle with complex proof problems that seemed to mean absolutely nothing. STEM classes are all the rage today, and nerds have stolen all of our brains and control all the money. But back in the ’70s, abstract math and science concepts felt impossibly remote. We were convinced none of this would never apply to the real world. Nobody would ever run up to you and suddenly ask, “Hey man, what’s the Periodic Table abbreviation for Magnesium?” Or “Quick: can you name the four parts of an algebraic equation?” Geometry was like that.

Our teacher was a gangly despot we’ll call Mr. Strand. He wore tinted glasses and cowboy boots, and existed in a forever state of mild rage over our inability to grasp the beauty of geometry. He would scribble on the chalkboard, some complex bit of nonsense, and build to an explanation of how one of us might incorrectly solve the proof, and turn to the class and erupt: “Tain’t right, McGee!”

The room was filled with empty faces. What was he talking about? What’s the reference? After 50 years, I’ve finally bothered to look this up, and Strand was quoting, or misquoting, an old radio sitcom called Fibber McGee and Molly, which ended production before any of us were born. The program’s catchphrase was “Tain’t funny, McGee.” Not that this helps any of us now, really.

The science-fiction element of Mr. Strand’s class occurred during the quiet time, when he just sat at his desk, while the class toiled in silence. Strand had an unusual posture. His legs and cowboy boots were splayed out in a V underneath the desk, as if presenting his alpha-male genitalia for all of us to see. And he would read book after book after book. Always science-fiction, always paperbacks. I have a memory burned into my brain of Strand, the legs and boots, the tinted glasses, and that day’s book, which was Robert A. Heinlein’s Have Space Suit—Will Travel.

I have ignored sci-fi books my entire life, and I’m pretty sure it’s because of Mr. Strand and his geometry class. Again, I’ve never bothered to investigate this further, until now. But it should be noted, with the passage of time and the power of internet research, that this particular Heinlein book title was WRITTEN FOR CHILDREN. So Strand wasn’t as ferocious as I’d always remembered. While we hacked through the jungle of geometric proofs, he read kids’ books. Like a child.

The next few years passed, and my sci-fi exposure moved on from cinema bleakness and Mr. Strand’s testicular reading habits. But one day, during our third or fourth year of college, my friends Steve and Bill told me, “We’re going to Kate and Damon’s, you should come along.”

Bill and Steve and I were all wannabe writer geeks, but we were still college students, and none of us had really published anything of note. And yet, they knew Kate and Damon, a married couple who were writers. This was the early ’80s in Eugene, Oregon, and as with Montana, you didn’t meet many people who were writers. Or even more rarely, someone who made a living as a writer. I agreed, and off we went in a taxi. It was pissing rain, because of course, Oregon. We knocked and they invited us inside.

I wasn’t familiar with their work, but Kate Wilhelm and Damon Knight were quite successful science fiction writers. Disciplined, and prolific. They’d both published dozens of novels and short stories. Nebula Awards, Hugo Awards. They were giants. And had been since the 1950s.

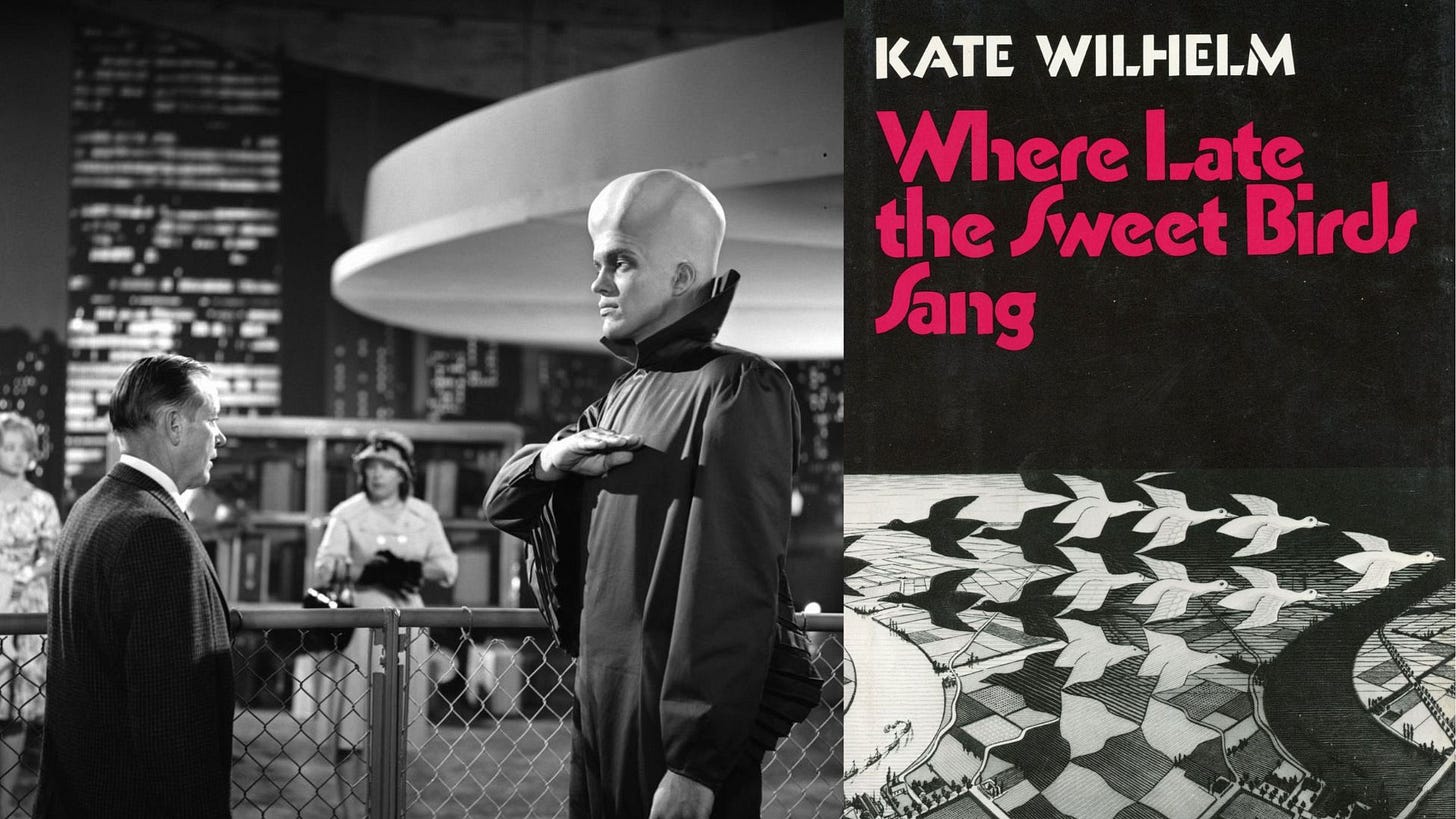

Damon Knight’s Twilight Zone episode “To Serve Man,” featuring 7-foot-tall actor Richard Kiel, and Kate Wilhelm’s best-known novel, with cover art by M.C. Escher.

One of Wilhelm’s career highlights was the post-apocalyptic novel Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, which was called “The best novel about cloning written to date.” Knight’s best-known credit is a short story which was adapted into “To Serve Man,” one of the most beloved episodes of The Twilight Zone. I recently watched the program, and although from 1962, and shot on a cheap budget, it still holds up, and features an exquisitely gruesome ending twist. None of this I knew at the time.

Knight and Wilhelm’s house was lined with bookcases, more than I’d ever seen in a single home. It was a magical, weird little pocket of literary life, tucked away from the Oregon rains. The three of us took a tour. There were bedrooms, and lots of plants, and they seemed just like normal people!

In their kitchen, lying on the table, was Knight’s latest rejection letter from Playboy. The standard “...isn’t quite what we’re looking for at this time, best of luck finding it a home elsewhere” type of message. Friendly, even familiar. He showed it to us three, and we read it with awe. He chuckled. Oh well, another rejection from Playboy.

Knight and Wilhelm seemed like nice, well-adjusted people. So…writers don’t have to commit suicide? They don’t have to take drugs, or drink like fish, or beat their kids? I was processing all of this heavily.

Someone opened another door, which led to a fully enclosed swimming pool, with this amazing bright red Communist banner stretched across one of the walls. They were swimmers—AND Communists!

We returned to the living room, surrounded by shelves and piles of books, and I remember we students all sat on the carpeted floor, and we spent the next few hours talking about writing. With writers.

Damon Knight passed away in 2002, and Kate Wilhelm died in 2018. My friend Steve Patterson, who grew up to be an award-winning Oregon playwright, died earlier this year. My college roommate Bill Cornett lives in Portland, is a writer and teacher, and is now, finally, on Substack.

I’m not sure which of their children ended up with that Vota Communista! banner, but I always coveted it in a sadly materialistic way. I kinda feel like you joined Steve and I on more than one exodus over to see them, though. Maybe not? Their monthly workshop anchored my meager creative output the half-decade I lived in Eugene. I at least learned I was not a science fiction writer.

Whenever I neglected my Geometry homework, I appended what Angle Side Side scribblings I turned jn with a notation along the lines of: These straight lines are obsolescent. Einstein demonstrated the universe is curved.

Cannot chastise you about never reading their work—I never finished that pilfered copy of Finnegan’s Wake you found under the couch after i abandoned it four lines in.

Heinlein was huge in Russia after the USSR fell apart. I was a big fan. In fact, it's from him that I learned about polyamory and socially creative marriages. It's hilarious to understand how conservative he actually was. But I still love him for opening up my world :)