Ken Kesey, Hawkeye Pierce, and Seagulls

A disappointing afternoon with Ken Kesey and Deadheads helped lead me to the next chapter in my life

Within an hour after my last college final, I got a job. My immediate desire was not really to pursue a career in local television, but there I was, shaking hands and becoming a salaried employee, before the diploma was even in my hands. It was the Reagan trickle-down, the American Dream in action!

I joined a crew of other young people in the production department of a CBS-affiliate TV station, helping deliver the mix of newscasts, talk shows, and other programming for the viewers of Eugene, Oregon. We adjusted lights, and operated cameras, and because I had a sliver of radio experience, I was also tapped to do voiceover work. A slide of the cast of M*A*S*H would appear on the screen, accompanied by my phony-yet-friendly tagline: “Hawkeye adopts a horse for the 4077th, with hi-larious results! Tomorrow night at 7, on KVAL-TV, Eugene!”

Once a week the SPCA would bring in dogs to be adopted, and we would film the “Pet Of the Day” segments, which featured each animal, looking into the camera, hoping for a better life outside the cage. Sometimes a dog would be freaked out by the equipment, and there was never any time to calm it down, so the footage would have to be used anyway. Viewers would see a terrified cocker spaniel cowering behind a pair of legs, with a cheery voice intoning, “This little guy’s name is Rusty, he’s two years old, and he loves children!” The crew would joke amongst ourselves, “Well, Rusty’s going to get gassed.”

My parents were overjoyed that I was “gainfully” employed. I was miserable. Is this it? Is this where I end up? Chain-smoking in a flannel shirt, fat and divorced, the voiceover king of southwestern Oregon? Some of these guys at the station, my God, they’re over 30.

I thought I wanted to be a writer. I read lots of books. Or at least I owned lots of books. I took creative writing classes. I kept a boxful of journals. But somehow I had blown through 16 years of education without ever once being published. I needed some more input. Some influence from a grander source, that would excite me again to the possibilities of literature.

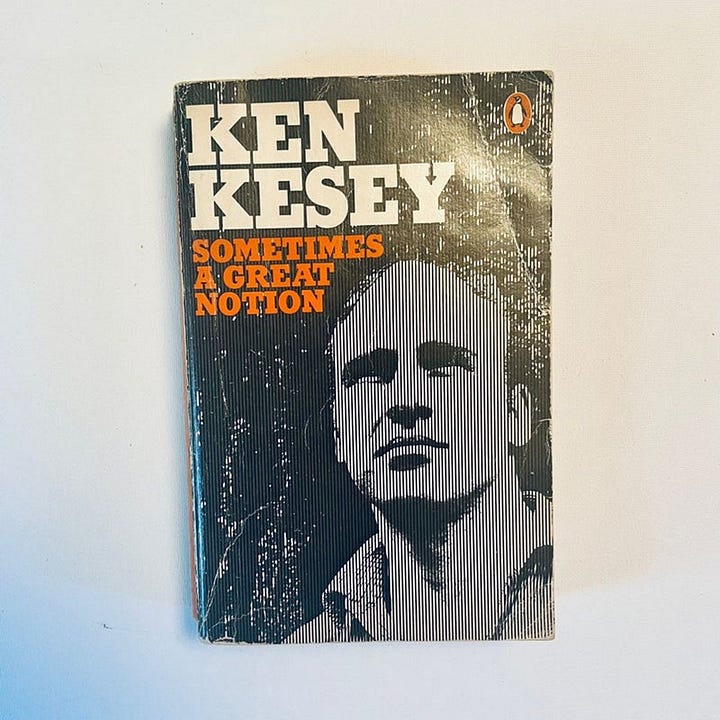

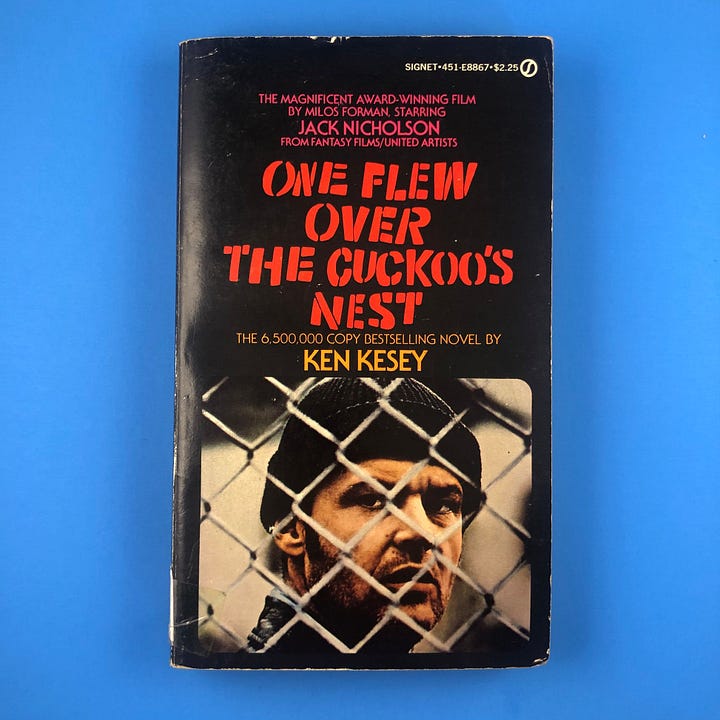

The flyers were all over Eugene: Ken Kesey was to give a one-day writers’ workshop. Kesey was the hometown hero. He grew up across the river in Springfield, and had graduated from my same “place of matriculation,” the U of Oregon. We’d all read Tom Wolfe’s book, and absorbed Kesey’s mythology as the 1960s LSD jester. But before he was a Merry Prankster, he was a brilliant novelist. The classic One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, published when he was only 27, written from the point of view of a Native American mental patient. He followed that with Sometimes a Great Notion, another daring work which incorporated multiple points of view, sometimes within the same sentence. Two groundbreaking, bestselling novels, right out of the chute. Post-Beat and pre-hippie, riding the groove of a nation increasingly losing its way. The Fifties were over, and the U.S. was on the cusp of mass confusion. It was as if Kesey threw a dart at society and hit the bulls-eye.

I initially loved the hippie bus tales, but the novels really spoke to me. His characters epitomized the American West: loggers, Indians, land developers, village crazies. I was from this part of the country. A fellow son of the soil. I could identify with all of it. Oh sure, I’d read some East Coast writers by that time. Plympton, Updike and the like. They were really smart, but so much neurotic hand-wringing. People had been living in that part of the country for 400 years. There was obviously something deeply wrong with them. That wasn’t the America I knew. It wasn’t Kesey’s America.

We all knew the acid took its toll. This was the early 1980s, and Kesey hadn’t written any fiction in nearly 20 years. But still, this was my first opportunity to hear an actual successful writer from my side of the Mississippi.

I walked into the campus classroom and immediately knew I’d made a mistake. Deadheads, everywhere. Their colorful yarn hats and wide-eyed stoniness. Faces crinkled over some cosmic joke that’s been going on since 1967.

Really, I had nothing against Deadheads. In Eugene they were inescapable. On campus everybody wore the buttons and T-shirts, even the professors. You’d go to a house party and the Dead was always playing on the stereo, with somebody saying, “Yeah, this is a soundcheck from Sweden, ’72…they played for four hours before the show even started.”

And I really had nothing against LSD at the time. I once went to the Oregon coast with a few friends, tripping heavily, and we discovered an injured seagull sitting in the sand. We all crept up slowly, wondering how we could save this poor animal, this innocent creature of God. Maybe its wing was broken. Maybe another animal had attacked it, and it was mortally wounded, waiting to die. We knelt down to inspect, and the gull looked at us. Stood up. And flew away. That was my big acid revelation: birds are not always injured.

Kesey strolled into the room late, smiling and wearing a dirty serape, sipping a smoothie through a straw. The organizers had collected stories from students, and he read through a few of them, making a few general comments, very simple adjustments. It reminded me of an article I once read about John Lennon in a recording studio. He never tweaked a lot of knobs. He would always make one simple adjustment.

But mostly, Kesey cracked jokes, which the saucer-eyed Deadheads devoured, laughing and giggling as though the whole experience was some sort of psychedelic riff. Nobody had any questions or comments. It was an amazing connection to witness, though. The crowd played off of Kesey’s every mannerism, every aside. Even a pause to sip the smoothie would elicit a ripple of awesomeness through the room. But it had fuck-all to do about writing.

I slunk out of the workshop in disgust. Maybe I should have gotten high. But then, I might not have remembered anything at all. I didn’t know what I wanted. I was 21, and impatient.

I don’t blame Kesey for coasting on his success. He had been a huge literary star. Hollywood made movies from his books. He was a counterculture icon. Truthfully, a life of kicking back and making Deadheads giggle would not be a bad way to make a living. Certainly a lot easier than sitting in a room writing books.

Having learned nothing, other than the John Lennon similarity, I continued my non-career for several more months, working at the TV station, sleeping with one or two of the female staff along the way. I performed sketch comedy in biker bars. I scribbled in more journals, wrote a couple of astonishingly bad one-act plays. And suddenly, as it often occurs to the young and the restless, I realized I could just leave.

I gave up my studio apartment, which overlooked a greasy dumpster behind a KFC, and packed everything I owned into a car. On my last night in Oregon, the production crew of the TV station threw me a going-away party. They made a cake and wished me well, and we laughed and partied until the sun came up. I woke up from the floor, said goodbye, and drove to San Francisco and got a job washing dishes. I haven’t watched an episode of M*A*S*H since, nor have I reread any Kesey. Both did what they were supposed to do.

This essay originally appeared in different form, in the Quiet Lightning anthology sPARKLE & bLINK #16.

Fantastic! I think everyone has an LSD-seagull story!

Most of the old hippies treated me as a kid in the punk scene with disgust. There was a definite faction of hippies in the poetry scene that hated everyone else. The glaring exception was Diamond Dave Whitaker, who was present in every scene in SF since the '50s. Is he still on the material plane with us?